This past January I headed into Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. I was going to a part of that community I know well – at the corner of Pender and Carrall. It’s a spot where, for more than two decades, I used to hang out, cop drugs, or deal.

This time, though, I was there to peddle something else – COVID vaccines. On the same corner I used to sell drugs, I was now pushing Pfizer. And with it, a little bit of hope for a community that’s been hit hard by two public health emergencies.

This week marked the fifth year since a public health emergency was declared because of toxic drug poisonings. People are overdosing and dying in communities across the province – across the country, really – but the DTES has been the epicentre in many ways.

It’s not because of overdoses alone. Many people in this community have been dealing with stresses of rapid gentrification, homelessness, compromised immunity, and poverty. And for the past year, COVID-19, which has compounded the impacts of all these things.

To make matters worse, physical distancing and isolation are extremely challenging in this community, where many residents live in communal housing with shared bathrooms and kitchens. It’s a tight-knit community where everyone has to rely on one another. The folks at Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Coastal Health (VCH) were especially concerned for residents who face homelessness, poverty, compromised immunity, and a lack of access to resources, including health services, as well as Black, Indigenous and people of colour and other vulnerable communities in the DTES, who are disproportionately affected by COVID. After a public exposure in August, cases increased through the fall and into winter. And though we didn’t see a significant spread of COVID, cases did begin to spike at the start of this year.

That’s why VCH formed an outreach team to support with the vaccination rollout in the DTES. I’m proud to be part of an amazing team of nurses who’ve been holding regular vaccination clinics in the community since January. Some people run from COVID, but this nursing team is running right at it in order to protect the community.

Each week we head down to a corner in the neighbourhood, set up a table, and lineup the syringes. The nurses do their thing and I do mine: hustling out to find people who haven’t been vaccinated.

When I bring someone over to the vaccination table, one of the first things I get asked is if I’ve been vaccinated. For many, that someone they know also has gotten the vaccine is reassuring and feels safer. This is a community that’s earned its distrust of the health care system, so we do what we can to build up that trust. It’s about providing a bit of human connection by meeting them where they’re at — on the street, where they live, next to their friends.

With that jab comes relief. I’ve seen it on people’s faces. Some have cried they are so overwhelmed.

Just weeks after the vast majority of those at risk received their first doses of vaccine, we have seen a dramatic decline in the number of new cases identified in the DTES. It’s taking a little bit of pressure off the community at a time when that’s badly needed.

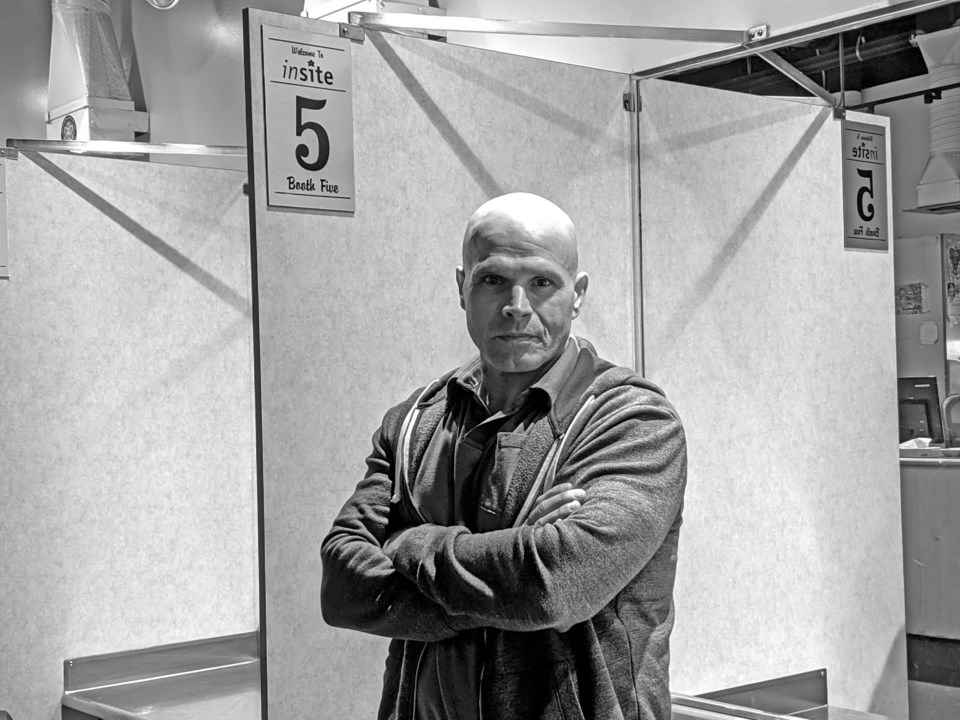

What’s amazing for me is living in that community for decades, homeless and struggling with substance use, and now I’m in the position to be able to go back to the same street corners where I once sold and used drugs to survive and offer people the vaccine.

It’s a little bit of hope during a tough time.

Guy Felicella is a Peer Clinical Advisor at the BC Centre on Substance Use. Follow him on Twitter at .