Last month, just before Christmas, the BC Coroners Service did what they’ve done every month now for nearly five years – they released their report on the number of drug overdose deaths in the province.

For families, friends, and communities that lost a loved one, behind those numbers is a life representing an unspeakable loss. For others who have been personally unaffected by substance use and the overdose crisis, they have become just that: numbers. A numbing monthly reminder of policy failure and inaction before moving on with their lives. This has become a sign of the empathy gap that is contributing to the social conditions that help fuel the overdose crisis – stigma, discrimination, isolation, and despair.

How we think and talk about substance use and people who use drugs has a profound effect. Many people, influenced by media stories and accompanying images of discarded needles in a puddle that accompany those monthly fatality reports, associate substance use with poverty and homelessness. They see drug use as the result of a series of poor individual choices, a sign of the “rock bottom” we hear so much about before people can get better. It’s a deserved, if not tragic, outcome.

But substance use is not the choice we believe it is. No one chooses to become addicted or to overdose. Substance use and addiction are often the result of an untreated trauma or pain, and struggles with substance use are a sign of an effort to treat something that society has failed to help heal.

This was certainly the case for me. Untreated trauma and undiagnosed ADHD led me at a young age to use drugs and sent me into a cycle of poverty, homelessness, violence, and criminalization.

By viewing struggles with substance use as the result of an individual choice, though, we dehumanize people and treat them as disposable. We see people struggling, but are deaf to their cries for help. We lack the ability to see outside ourselves and to empathize. Instead we judge.

I experienced this first hand. My own drug use made it easy for others to treat me like a criminal, as lower than an animal. It made it easy to see me as a lost cause, my status the deserved result of a series of bad choices.

I, like others who use drugs, felt the looks from society, and recognized the judgment and disgust. I tried to act like I didn’t care, but I internalized that shame. I withdrew, I became more isolated, and I wouldn’t reach out to ask for help.

It’s this shame and isolation that drives people to use drugs alone. And this is how many people who overdose die – alone. As much as the toxic, poisoned drug supply, it’s stigma that is fuelling the overdose crisis.

Racism, poverty, homelessness, and criminalization contribute to stigma and discrimination. They create the social conditions that make it easy to dismiss as person.

We have a right to be angry and upset about overdoses and what we see in those monthly reports, but we’re wrongly directing our anger toward the people who use drugs and are dying instead of those who have the power to make change.

We need to close the empathy gap and stop blaming the individual for the policy failures that created the conditions for struggles with substance use in the first place.

This is where the choice actually lies: to have compassion for people who are struggling or to continue to dehumanize those around us who may be suffering silently alone.

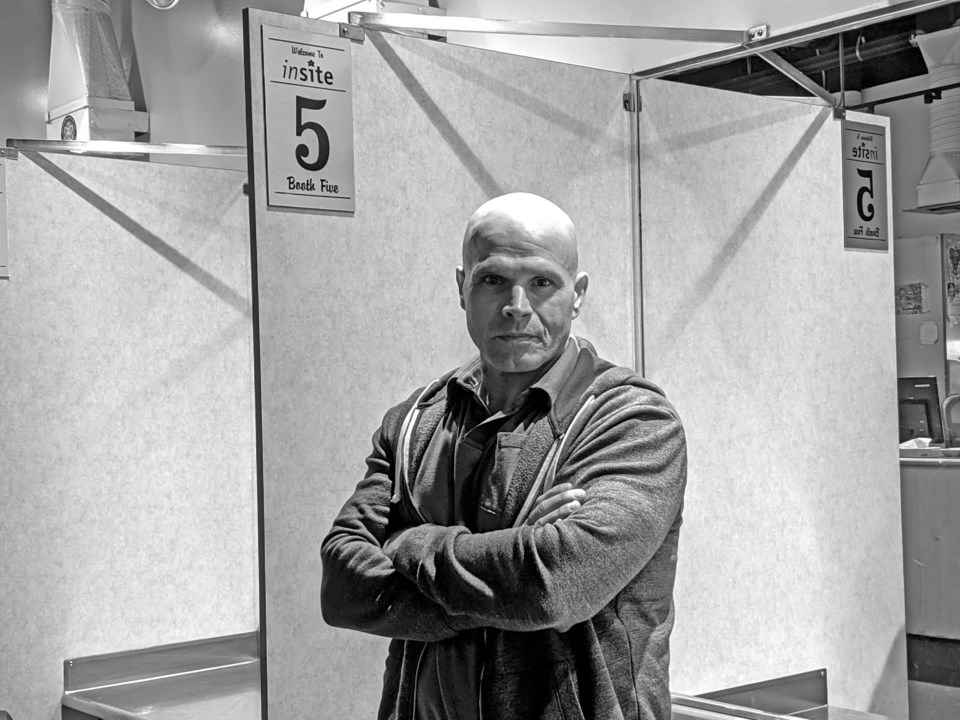

Guy Felicella is a Peer Clinical Advisor at the BC Centre on Substance Use. Follow him on Twitter at .