Canada’s Minister of the Environment and Climate Change took too long when he waited eight months to recommend cabinet issue an emergency order to protect the northern spotted owl — Canada’s most endangered bird, a federal judge has ruled.

The June 7 decision hinges on how government interprets “unreasonable delay” under the Species at Risk Act. It will likely guide Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault and his future counterparts to act swiftly to protect species his office deems are under severe and imminent threats, said Joe Foy, protected areas campaigner with the Western Canada Wilderness Committee.

“They delayed. They delayed. And they delayed,” Foy said. “If a thing is an emergency, the environment minister needs to act like it’s an emergency. Follow the law. Sound the alarm.”

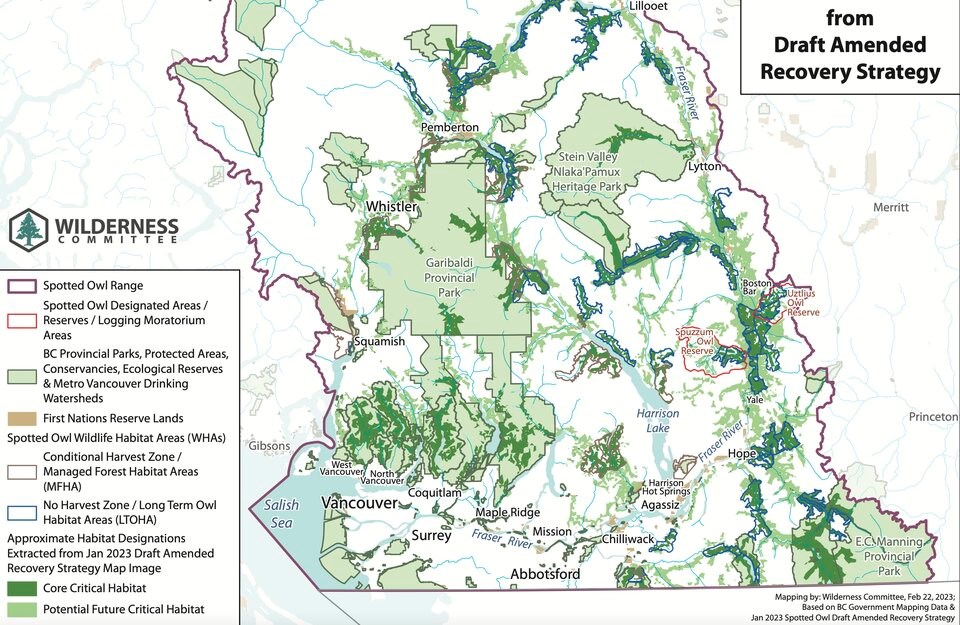

The decision stems from June 2023, when lawyers for the Wilderness Committee filed a request for a judicial review before Canada's federal court. In it, they sought to pressure the minister to follow through on his plan to protect more than 2,500 hectares of habitat in southwestern British Columbia at risk of being logged between April and November 2023.

Guilbeault had already agreed to make that recommendation to cabinet five months earlier. At the time, the minister agreed the protection order was necessary because, if logging continued, the survival and recovery of the species was “highly unlikely.”

But letters between Guilbeault and B.C. Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Nathan Cullen showed the province was more concerned about noise from the Trans Mountain pipeline than logging of the owl’s habitat.

In his decision, Justice Yvan Roy wrote that the B.C. government “disagreed with the conclusion that there continued to be an imminent threat to recovery” and that existing measures, including a captive breeding program run out of a farm in Langley, B.C., were enough to protect the species.

Spô'zêm First Nation Chief James Hobart said the federal government's assessment on the status of the spotted owl should have rung alarm bells for all levels of government.

“‘Imminent threat’ in our territory? If it’s water, we head to the hills. If it’s fire, we head to the water. It’s an emergency,” Hobart said.

Spô'zêm — whose territory includes the Spuzzum and Utzlius Creek watersheds, flashpoints where the last two wild spotted owls in Canada are known to reside — was one of two First Nations who responded to the federal call for consultation. Both backed Minister Guilbeault's emergency order recommendation.

But by the time the case was heard in a Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»federal court mid-October 2023, Guilbeault had already recommended an emergency protection order to cabinet, where it was turned down. It’s not clear why the protection order was denied as .

For Hobart, the province derailed the federal government’s plan to protect the endangered owl, and what he described as cabinet’s failure to directly consult First Nations made the situation even worse.

“We were screaming from the mountaintops saying ‘no, stop this,’” he said. “You know how that feels? Your input feels useless.”

In an emailed statement, Guilbeault said his government is committed to recovering the owl species through a tripartite agreement between First Nations and the federal and provincial governments.

“We are carefully considering the decision of the court and reviewing our process accordingly to ensure efficient process that strive to deliver positive outcomes for species at risk in Canada,” he said.

Glacier Media reached out to B.C.’s Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship but neither responded to questions by publication time. ​

Habitat decline main threat to owl, says judge

B.C.'s northern spotted owl population was once thought to have totalled up to 500 breeding pairs. But when the federal government released its first recovery strategy for the owls in 2006, there were 22 birds in the wild.

A year later, a B.C. government-backed breeding and release program was launched with the goal of boosting the population to 250 mature owls within 50 years. The first-of-its-kind program has faced a number of obstacles. In the intervening 17 years, the number of wild-born spotted owls has plummeted to one.

Two owls bred in captivity and released into the Fraser Canyon in 2022 were later found dead; and of the two more released in September 2023, one survived the winter, and the other was found starved to death, said Hobart.

An updated federal recovery strategy released in January 2023 found the goal of restoring a population to 250 mature birds will take more than 50 years.

Logging — alongside roads, railroads and hydro and gas lines — remain primary threats to the spotted owl, wrote the judge in his decision.

Roy said the spotted owl is threatened by climate change, noise disturbance, and competition over prey and habitat with the invasive Barred owl. But the evidence before the court, he said, identified the loss of mature old-growth forest habitat from logging as the primary reason for the owl’s decline.

​​The federal environment ministry “insisted” there has been cooperation with British Columbia to protect the spotted owl. But those efforts “have been less than stellar,” Roy said.

“The evidence is clear that the habitat is a serious concern for the survival and recovery of this particular endangered species,” said the judge.

When the case was heard last fall, lawyers for the Wilderness Committee told the judge it was likely too late to determine the fate of the spotted owl but a decision in the case could serve the survival of at-risk species in the future.

“The question then becomes, why did it take from January 17, 2023 to September 26, 2023 to make the recommendation for the Governor-in-Council to issue an emergency order?” wrote Roy in his decision.

'Parliament has spoken'

Lawyers for the ministry argued the minister needed time to consult provinces and First Nations, and analyze how protecting habitat would impact society and the economy so he could present an “informed recommendation” to cabinet.

But Kegan Pepper-Smith, a lawyer with the firm Ecojustice representing the Wilderness Committee, argued in court last fall that the eight-month wait was the latest in a series of “unreasonable” delays — part of a “talk-and-log approach” that has failed to protect the owl.

“This is an important decision for at-risk species across the country facing imminent threats to their survival and recovery. Ministers must act with urgency. No longer can they rely on extraneous considerations and processes, like negotiating with the province, to justify delay,” said Pepper-Smith in a statement.

In a summary of the Wilderness Committee’s position, Justice Roy wrote that Indigenous rights and the socio-economic impact of an emergency order recommendation — in this case, to halt logging — were “not irrelevant” but “can only be justified if the delay does not jeopardize the recovery of the species.”

​The federal judge found that while the minister is entitled to interpret the Species at Risk Act, that interpretation “must be reasonable.” The court was not asked to determine how long of a delay would be reasonable. Roy said he was nevertheless “tempted to agree” with the Wilderness Committee’s position that the timing should respond to the nature and severity of the threat.

And while consultations with the province are not discouraged, Roy said in the case of the spotted owl, “a long delay cannot be justified.” As the judge put it, “Either the threats are imminent or not. Either the threats concern the survival or recovery of the species or they do not.”

Added Roy: “Parliament has spoken: the purpose of the Act is to prevent species from becoming extinct and to provide for the recovery of endangered species as a result of human activities.”

“The situation, by its very nature, is urgent.”

​Owl habitat still being approved for logging, says group

Foy said the decision was “bittersweet.” On the one hand, he said it’s a vindication that delaying action under Canada’s Species at Risk Act won’t be tolerated by the courts; on the other, he said logging has continued on land flagged by the federal government as critical owl habitat.

Between May 12, 2023 and April 15, 2024, 91 cutblocks totalling 564 hectares have been approved for logging on land flagged as core and potential future critical habitat for the owl, according to Wilderness Committee mapper Geoff Senichenko. Another 249 hectares across 30 cutblocks are pending approval.

“This spring, I’ve been out there. It’s still being logged,” said Foy. “Wood products are increasingly sold as environmentally friendly products — here in Vancouver, for taller and taller buildings.”

“And only a few kilometres away from where these buildings are being built there’s this hellscape where habitat for critically endangered species is being cut.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated with comments from Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault.