Canada’s federal cabinet has turned down a request from its own environment minister calling for an emergency order to protect 2,500 hectares of critical habitat, home to the last wild-born northern spotted owl in the country.

The decision, revealed in court documents and through a letter to First Nations, comes eight months after federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault said he would recommend cabinet protect two patches of forest near Spuzzum and Utzlius creeks in B.C.’s Fraser Canyon.

The Oct. 10 letter, directed to “Chief, Counselors, and Lands Managers” and signed by the Pacific region director of the Canadian Wildlife Service, said the Canadian government has determined the emergency order is not “the preferred approach at this time.” Instead, it endorsed “a collaborative approach” between Ottawa, the B.C. government and Indigenous Peoples.

Earlier this year, a threat assessment from the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) indicated logging “poses an imminent threat to the survival of the species” and that 2,500 hectares of habitat in the Fraser Canyon has a “high potential to be harvested over the next year.” Allowing the logging of the two areas would make recovery of the species “highly unlikely,” wrote Daniel Wolfish, the director general of the CWS’s regional operations directorate.

Spô'zêm First Nation Chief James Hobart, whose territory sits adjacent to the owl habitat and has played a leading role in recovery attempts, said the cabinet decision to turn down the emergency order was so upsetting he had to have someone read the letter to him a few passages at a time.

“These are almost extinct. And then, what next?” said Hobart. “True colours are being shown on their side.”

Court hearing won't help spotted owl

In June, the Western Canada Wilderness Committee filed a court action asking a federal judge to declare the delay in issuing an emergency order “unlawful” and to compel the minister to follow through on his obligations under the Species at Risk Act within 15 days of the court's judgment.

The case is set to be heard next week, mere days after cabinet’s decision to turn down the emergency order was made public.

Andhra Azevedo, a lawyer with the firm Ecojustice, which is representing the Wilderness Committee, said the cabinet decision means the case will no longer impact federal action to protect spotted owl habitat. But it could still set a precedent by forcing ministers to quickly follow through on plans to recommend an emergency order — whether that’s northern spotted owls, southern resident killer whales, or caribou, Azevedo said.

What will happen to the last remnants of spotted owl territory in Canada is less clear. In the months since Minister Guilbeault said he would declare an emergency order, logging companies have been given approval to continue harvesting in the area, according to research by the Wilderness Committee.

Joe Foy, the Wilderness Committee's protected areas campaigner, said his group took federal maps outlining what forests need to be protected in order to save the species in Canada and overlaid them with provincial maps showing pending and approved forest cutblocks in B.C.

Foy was part of a team that visited the Fraser Canyon forest sites at the end of May. He said they found logging had already started in places where critical spotted owl habitat was meant to be protected.

“Logging is nailing these areas under permit from the province of B.C.,” Foy said at the time. “It freaked us out. It goes against what the federal government has been telling us since February.”

At federal court next week, Azevedo said they would be submitting new evidence that outlines the extent of logging in owl habitat flagged for protection.

“It’s not going to bring back that old growth that was logged. It’s not going to bring back the two owls who died,” said Torrance Coste, Wilderness Committee’s national campaign director.

“But hopefully, it’s going to set a precedent — that an emergency order meant to protect a species won’t be delayed months and months and months.”

Historic range a fraction of what's left

About 40 centimetres tall with dark plumage, dark eyes and no ear tufts, the northern spotted owl ranges from southern B.C. through Washington, Oregon and into northern California. A subspecies of the spotted owl, it was listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act in 2008.

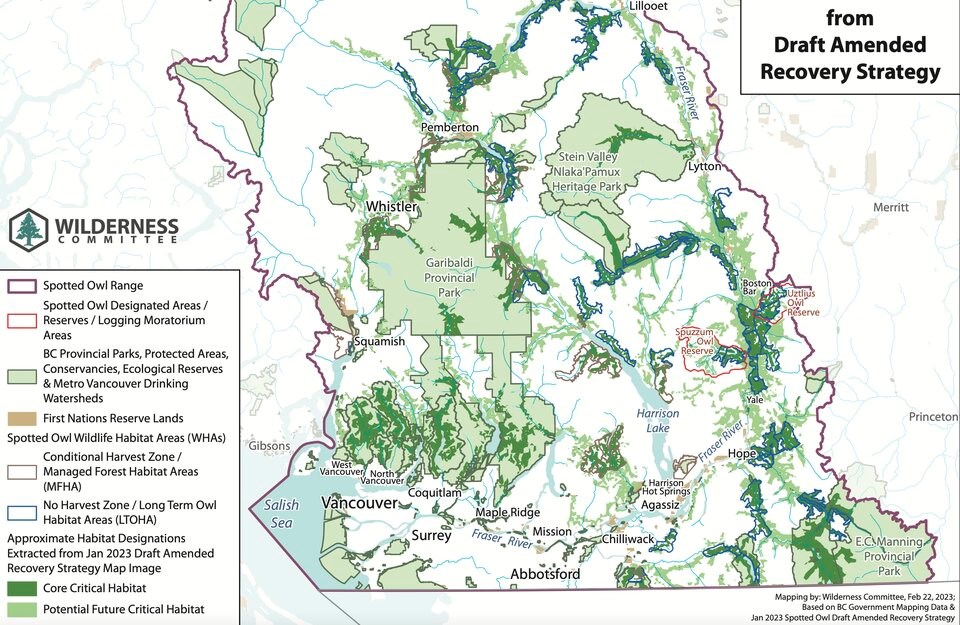

The historic core critical habitat for the northern spotted owl stretches from the Lower Mainland, through the Squamish Valley to Whistler, Pemberton, down the Fraser Canyon and south past Hope.

Today, however, only one wild-born spotted owl remains alive in all of Canada. Earlier this year, remains of two owls released from captivity in 2022 were found with their transmitters outside protected areas. The third was returned to the breeding centre where it is recuperating after being hit by a train.

​Last month, two male owls — named 'sítist’ (te-syst) and ‘wíkcn’ (week-chin), translated to English as “Night” and “I see you” from Spô'zêm — were released through the .

The province says it has protected more than 280,000 hectares of spotted owl habitat, enough to support a future population of 125 breeding pairs.

Hobart says the B.C. government has dropped six cages in his nation’s territory, too many he says for the rate at which the breeding program can reintroduce more owls.

“This is all smoke and mirrors,” he said. “They’re putting up cages they never may use. They’ll never populate all of them. It’s just a matter of looking good to the mother ship, to show Canada they’re doing something.”

'Messengers of the forest'

Some experts say recovery of the species is possible through breeding programs and introduction of wild owls from the United States. But first, the owls need intact old-growth forests, where they nest in woody cavities and broken large diameter trunks.

A few patches of unconnected old-growth forest won't be enough for the northern spotted owl to survive. That's because the owl species only flies over old-growth canopy, and when fledglings are born, they need connected forest corridors to spread out into new territory.

More than another species on an endangered list, the Spô'zêm people consider the owls the “messengers of the forest” as their health reflects the state of their old-growth home.

Giving up on the owls is not an option, Hobart said. Describing the cabinet decision to turn down the emergency order as a “speed bump,” he said now is the time to rally other First Nations to protect the habitat of the last northern spotted owls — if not for their sake then for the next species that appears on the at-risk list.

“I guess in times like this we become unpopular. But the government hasn’t seen anything yet,” he said.

“It’s going to be a long hot summer if they think they’re going to be logging again next year.”