LONDON (AP) — A teen charged with killing three girls and wounding 10 other people in a in England refused to speak as he appeared in court Wednesday to face new charges of possessing a deadly poison and a terror charge linked to possessing an al-Qaida manual.

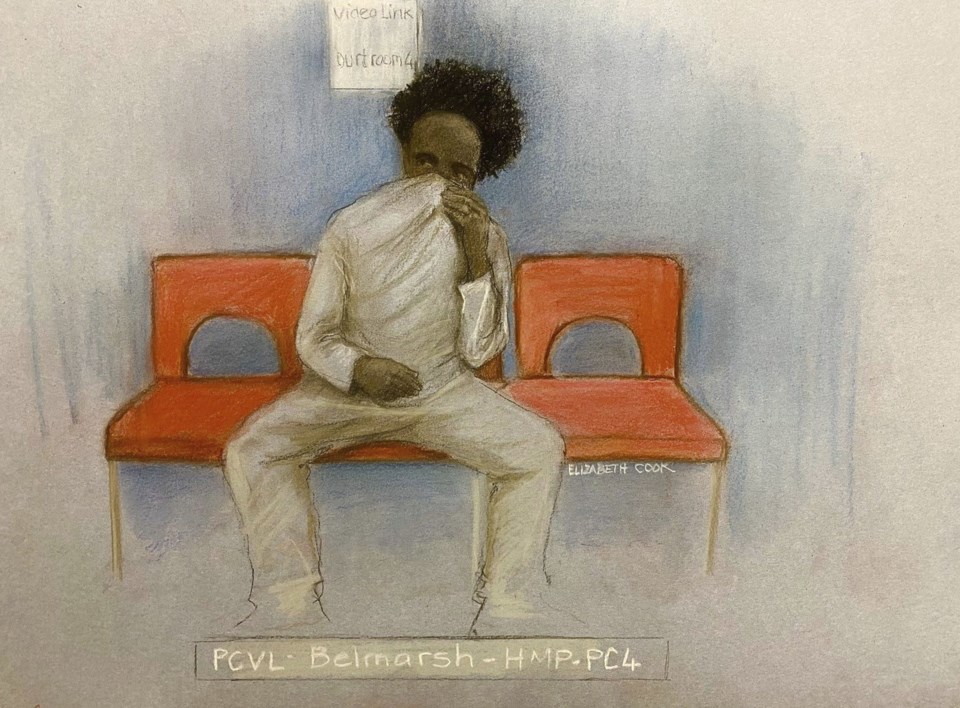

Axel Rudakubana, 18, who appeared in Westminster Magistrates’ Court by video link from Belmarsh prison in south London, pulled the top of his gray sweatsuit over his nose and wouldn't confirm his name or respond to other questions.

“Mr. Rudakubana has remained silent at previous hearings as well,” defense lawyer Stan Reiz said. “For reasons of his own he has chosen not to answer the question.”

Reiz said Rudakubana has a history of mental health issues.

Rudakubana was charged in August with murdering three girls — Alice Dasilva Aguiar, 9, Elsie Dot Stancombe, 7, and Bebe King, 6 — and stabbing 10 other people on July 29 in the seaside town of Southport in northern England. Police on Tuesday stressed the stabbings have not been classed as a “terrorist incident” because the motive is not yet known.

He was charged Tuesday with for production of a biological toxin, ricin, and possession of information likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing to commit an act of terrorism.

Merseyside Police said they found the poison and a document on his computer that included an al-Qaida training manual titled “Military Studies in the Jihad Against the Tyrants” when they searched his home after the rampage.

Ricin is derived from the castor bean plant and is one of the world’s deadliest toxins. It has no known vaccine or antidote and kills cells by preventing them from making proteins.

The killings occurred on the first week of summer vacation as about two dozen young girls danced to music by Swift at Hart Space, a community center that hosted everything from pregnancy workshops to women’s boot camps.

Rudakubana also has been charged with 10 counts of attempted murder for the eight children and two adults who were seriously wounded. Leanne Lucas, who led the class, and John Hayes, who worked in a business nearby and ran to help, were credited by police with trying to protect the children.

The stabbings fueled far-right activists to stoke anger at immigrants and Muslims after social media the suspect — then unnamed — as an asylum seeker who had recently arrived in Britain by boat.

Police quickly set the record straight that Rudakubana was born in Wales and British media reported that he was raised by Christian parents from Rwanda.

But within hours of a somber community vigil to mourn the Southport victims the day after the stabbings, an unruly mob attacked a mosque near the dance studio and tossed bricks and beer bottles at law enforcement officers and set fire to a police van.

Rioting spread across England and Northern Ireland that . More than 1,200 people were arrested for the disorder and hundreds have been jailed.

The judge ordered the new charges to be transferred to Liverpool Crown Court, where prosecutors will ask for them to be consolidated with the murder and attempted murder charges. Rudakubana faces a hearing in Liverpool on Nov. 13.

The new charges prompted new claims by some on the political right that the government and police had concealed important information about the suspect.

“We don’t know the reason why this information has been concealed,” said Conservative lawmaker Robert Jenrick, one of two candidates to lead the opposition party. “Why has it taken months for the police to set out basic facts about this case that it is reasonable to believe were known within hours or days of this incident occurring?”

Britain’s contempt of court laws restrict what information can be reported about a suspect before their trial, in order to ensure a fair jury trial.

The Crown Prosecution Service said Wednesday that “it is extremely important that there is no reporting, commentary or sharing of information online which could in any way prejudice these proceedings.”

Many argue that the rules can be counterproductive in the social media era.

Jonathan Hall, a government-appointed lawyer who oversees U.K. terrorism legislation, said “if there is an information gap, particularly in the mainstream media, then there are other voices, particularly in social media, who will try and fill it.”

“Quite often, there’s a fair amount of information that can be put into the public domain, and I think I detect that the police are trying to do that,” he told the BBC.

___

Jill Lawless contributed to this story.

Brian Melley, The Associated Press