Clear-cut logging in the upper reaches of two B.C. rivers led to a massive increase in downstream flood size and frequency, raising further questions over the influence tree harvests may have as climate change makes flooding worse, a new study has found.

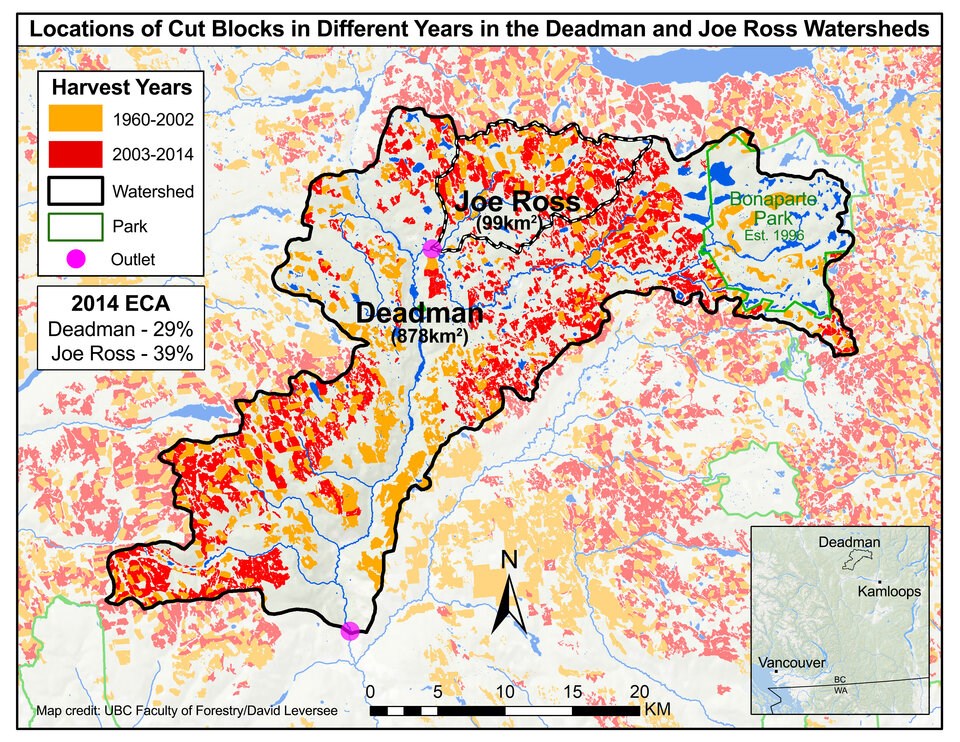

The , published in the peer-reviewed Wednesday, examined Deadman River and Joe Ross Creek, two nested tributaries of the Thompson River whose watersheds climb roughly 60 kilometres north and northwest of Kamloops, B.C.

Borrowing techniques from climate attribution science and streamflow data going back to the 1960s, the authors used computer models to compare two scenarios: one where clear-cut logging did occur and one where it didn’t. Then they filtered out the effects from climate change. The first of its kind study in B.C. offers a glimpse into how logging impacts flooding at a large scale in forested watersheds.

At Deadman River, the models showed logging only 21 per cent of the watershed led to a 38 per cent increase in mean flood levels; at Joe Ross Creek, the same amount of logging spiked flood levels by 84 per cent.

But the biggest surprise, said to Younes Alila, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s department of forest resources management, was how frequent small, medium and big floods were expected to return when clear-cut logging occurs.

In both rivers, seven-year and 20-year flood events became twice and four times more frequent. Fifty-year flood events were found to occur six times more often. And floods so rare they happened once in a 100 years increased in frequency 10 fold, meaning a flood of that size would return once every decade instead of once a century.

“This research is showing you that all these events — small, medium, large, very large and biblical — are becoming dramatically more frequent,” said Alila, who co-authored the study with his graduate student Robbie Johnson.

“The larger the events, the more frequent it becomes as a result of this level of logging.”

How forests limit flooding

The researchers suspect the increase in flooding occurs because logging operations diminish a forest’s ability to limit snow accumulation, which later turns to meltwater when temperatures climb.

An intact forest captures snow in its bows, where it can evaporate back into the atmosphere. What snow does fall through the canopy is shaded by the trees around it, only subjected to filtered light from the sun. A clear-cut forest block, on the other hand, accumulates deeper snowpacks, and when spring comes, that snow tends to melt without the attenuating effects of forest cover.

But every river system is different — clear-cut watersheds facing south will get more sun, leading to spikes in meltwater as seen at Joe Ross Creek. The upper reaches of Deadman River face a different though just as risky scenario. A cut block sitting at the same elevation, such as a flat plateau, can accumulate deep snowpack that will eventually melt all at once. Downstream, all that meltwater pours into a river at once, driving up flood levels.

Those differences matter to help calculate the individual risk and frequency that a river will flood. But Alila says the effects of clear-cut logging across B.C.’s streams and rivers needs to be considered at scale. Joe Ross Creek flows into Deadman River. And through the Thompson River, both their waters pour into the Fraser River, the province’s largest.

Floodwaters pumping silt downstream raise risk of dike breaches

Alila says the accumulation of bigger and more frequent floods across the tributaries of the Fraser River could have drastic impacts on Metro Vancouver, where it empties into the sea. That’s because bigger and more regular floodwaters will scour sand and silt from the high reaches of river systems feeding the Fraser.

Suspended in the rushing water, silt particles will rush thousands of kilometres downstream. As the river slows near the sea, they will eventually sink, creating deep sand banks next to some of B.C.’s densest urban areas.

The small headwaters where heavy logging has taken place may be far from the downstream populated urban area. But eventually, those floodwaters will carry and deposit the fine sediment next to the dikes protecting communities.

Wildfire can accelerate those effects (a major reason why Alila and Johnson ended their study in 2014 before fire ripped through the area).

When a forest burns, it tends to create an impermeable ground layer of waxy residue, which acts like a slide for runoff to flow downhill and into rivers at a rate orders of magnitude larger than the effect of conventional logging, says Alila. Last year, a B.C. company that helps make sense of satellite data says it between the 2021 wildfires and several bridges and sections of highway washed away during 2021's powerful floods.

“It does not allow the snow to melt or rain to infiltrate into the soil, and therefore, the landscape acts as a parking lot,” he said.

​Still, said Alila, logging has a powerful impact, and the combined effect of clear-cutting and wildfire could lead to a different kind of flood risk far from Interior rivers like the Deadman or Joe Ross Creek. ​

​Part of that is due to inadequate infrastructure. In 2016, the reported two-thirds of the assessed dikes in the Lower Mainland scored as poor to fair, while 18 per cent were classified as unacceptable to poor.

“Few of the dike segments assessed meet current provincial standards, and no dikes fully meet provincial standards,” stated the report.

Five years later, and just months before catastrophic flooding hit much of B.C. in 2021, the council released a commissioned warning that there are “no guidelines” and “limited information” when it comes to channel maintenance. And when it came to dikes — the failure of which led to widespread flooding in places like the Sumas Prairie region of Abbotsford — the report found “many known gaps” remain.

“The current model for flood risk governance in B.C. is broken,” concluded the report.

Alila says a big part of the risk comes from scoured sediment already building up alongside dikes at the river’s mouth. Like placing too many ice cubes in a full glass of water, the Fraser’s waters will eventually have nowhere to go but over or through a breached dike.

“We are basically in a vicious circle,” he said.

Logging-triggered floods already bringing victims compensation

Alila has spent the past two decades investigating the impacts of logging on flood risk. But he said this is the first study that demonstrates that the power of the forest to mitigate against flood risk dramatically increases as the scales get bigger.

“The larger the catchment, the more powerful is the forest at mitigating flood,” said Alila.

B.C.’s reliance on clear-cut logging is already having clear and present impacts on people's homes and lives.

In 2022, Alila successfully acted as an expert witness in a lawsuit brought by a family against a logging company and the province after their home flooded. The Smithers couple had claimed the province was negligent in its failure to take reasonable care to ensure their property in northwestern B.C. would not be damaged by the logging.

Hired by the couple, Alila prepared a 70-page report outlining his conclusion that clear-cutting “supercharged” flows in the watershed, with snow and snowmelt the key factor.

At the time, Alila described the evidence that logging was the culprit as a “slam dunk.”

More recently, he has been advising the provincial government on a future flood management strategy. He says his latest study points to a need for government to integrate those plans with how it manages forests.

“The entire province is at the crossroads deciding right now on how to manage the timber supply area over the next five to 10 years,” Alila told Glacier Media. “All of our landscape, with no exception, is sitting at a much higher risk than we were led to believe by the government and the industry.”

“And you can blame that on the conventional clear-cutting.”

With files from The Canadian Press