Addressing traffic gridlock is one of the goals of the mobility pricing commission. file photo Mike Wakefield

Addressing traffic gridlock is one of the goals of the mobility pricing commission. file photo Mike Wakefield

An independent commission set up to examine whether a driving toll could help reduce traffic gridlock has narrowed down the options that might be workable in the Lower Mainland.

Tolling drivers who travel past certain congestion points or charging them based on the distance driven are two of the options the 14-member Mobility Pricing Independent Commission selected for more detailed study in a report released Tuesday.

The commission, set up to examine if some kind of tolling system might reduce traffic congestion which grips many areas of the Lower Mainland during morning and afternoon rush hours, is to present a final report to TransLink’s mayors’ council by the end of April.

This week’s report inches the commission closer to recommending some kind of road toll likely to be politically unpopular with many members of the public – particularly those who commute to work daily in their vehicles – but which could also win support if it manages to unclog some of the area’s driving chokepoints.

The commission settled on the two options after studying the pros and cons of tolling systems in other jurisdictions and receiving feedback from both elected officials and the public.

In the first approach, drivers would be charged if they either went past a specified congestion point or drove within a defined area, like the downtown core of Vancouver. In the second approach, drivers would pay a toll based on the number of kilometres they drive. Both approaches could include variations so that drivers might only be charged at certain times of day or days of the week.

It’s possible that distance charges could also vary depending on where the driver travels, said Daniel Firth, executive director of the commission.

Both Firth and commission chair Allan Seckel acknowledged, however, that the first approach would likely be easier to put into practice. Privacy concerns are one hurdle to distance-based charges, because of the need to track where vehicles are going.

Both Firth and Seckel said this week the idea of congestion point or “cordon” charges doesn’t necessarily mean putting tolls on many or all of the Lower Mainland’s bridges.

But Seckel acknowledged that is likely one of the options on the table.

“Could they end up being on the majority of the bridges? I’m not going to say that’s not possible or even likely,” he said.

Seckel said the commission must also look at what the impact of putting a toll in one location might have on traffic patterns throughout the region, including the impact on local communities.

The commission started out looking at 10 different “mobility pricing” systems, but narrowed it down after concluding some of them would not address all of the goals identified. A vehicle levy, for instance, could be good at raising revenue but would likely have little impact on congestion, said Firth.

Making any tolls affordable, having adequate transit options in place and making sure any tolling system is “fair” were key issues pointed out by the public, according to the report.

Of those, fairness is the most challenging, because people have very different ideas about what that means, said Seckel.

So far, for instance, there are no good answers about how to address issues like the commutes of Seaspan workers, most of whom drive from homes off the North Shore to a work site not easily accessible by transit.

“We’re aware of that issue,” said Seckel. “It’s one of the things we’re grappling with. We haven’t resolved it.”

According to the commission’s report, areas where congestion tolls have been put in place have all been successful in reducing congestion and generating revenue to fund transportation improvements.

Generally, about two-thirds of the public are opposed to the tolls before they go in, but that opposition softens once people see the benefits, according to the report.

According to the report’s summary of public feedback in the Lower Mainland so far, while most people see traffic congestion as a problem, they are also opposed to the two main tools being examined to deal with it. Only 32 per cent of those responding supported people paying more based on the number of kilometres driven. Only 35 per cent supported paying more to drive in gridlocked areas or at rush hours.

About 6,000 people in Metro Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»weighed in through an online survey with thoughts about traffic and congestion issues. The majority of those offering opinions appeared to be male, relatively well-off, not have children and more likely to live in the City of Vancouver, according to information in the report. About 13 per cent of the responses were from people living on the North Shore.

According to the commission’s research from other jurisdictions, most drivers won’t change their behaviour when tolls are put in place. But only a small number of drivers need to do that to make a big difference to traffic congestion.

“Get a few of the discretionary trips off the road at a particular time of day and you can make a huge difference,” said Seckel.

The report also acknowledged that not everyone benefits equally under a toll system. Some people see large improvements in their day-to-day travel while others may see a marginal difference or be worse off than before.

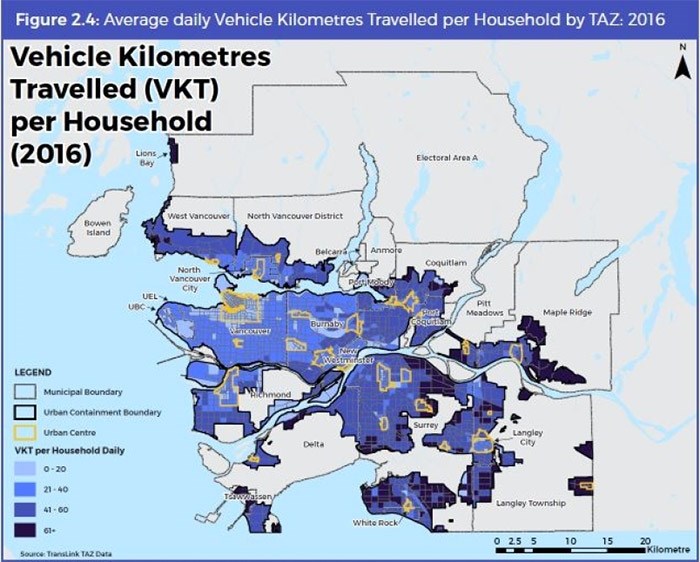

A map showing average number of kilometres driven per household around the Lower Mainland. Darker colours mean more driving. – graphic provided Mobility Pricing Commission

A map showing average number of kilometres driven per household around the Lower Mainland. Darker colours mean more driving. – graphic provided Mobility Pricing Commission

In Stockholm, the biggest change when tolls were brought in were people commuting to work deciding to take transit, according to the report.

Tolls in Stockholm range from $1.70 to $5, with a maximum charge of $16 a day. In London it costs $19 to drive into the city centre on a weekday. The tolls have resulted in cutting car traffic by between 16 and 20 per cent and cutting congestion by about 30 per cent, according to the report.

The report also referenced one failed experiment in congestion pricing: New York City, where a plan was studied and recommended but political concerns about how the plan would impact voters in outlying boroughs essentially deep-sixed it.

Seckel side-stepped a question about how likely it is that any tolling regime would prove palatable for municipal and provincial politicians.

“Because we were created as an independent commission it’s probably not wise for us to be speculating on politics,” he said.

The next phase of public engagement – both online and in person - will begin in mid-February and continue until mid-March. Find the report and information at .