Given that Spotify dominates about a third of the world’s streaming market, indie artists can be forgiven for thinking the key to success is getting their original music on the Sweden-headquartered company’s playlists.

But even if an artist’s song gets streamed 100,000 times on Spotify, at US$0.003 to US$0.005 per stream – depending on whether streams come from free or premium accounts – those plays would only generate between $400 to $680 for the artist – a sum that likely wouldn’t cover the cost of recording the song in a professional studio.

Streaming doesn’t pay very well, and it’s a very crowded space.

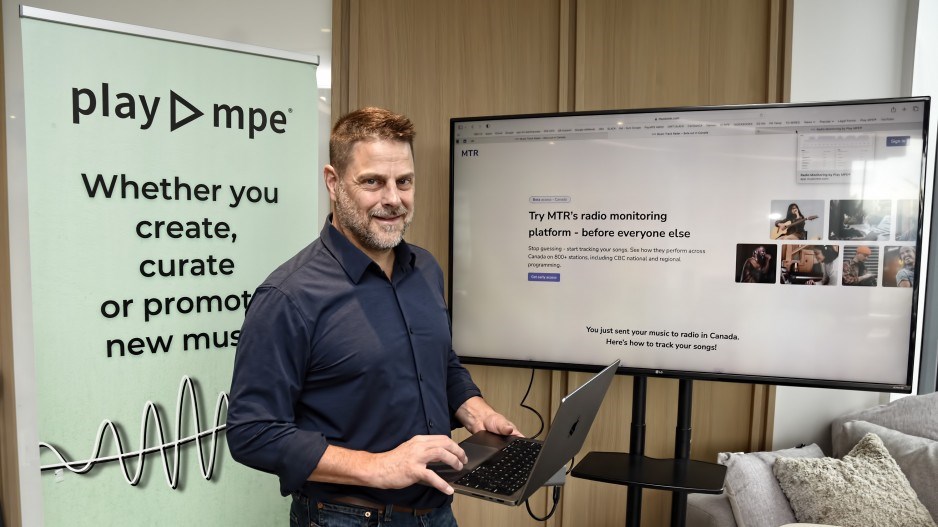

While it may sound old school, getting a song on the radio is still the best way of getting your music heard, says Fred Vandenberg, CEO of Destiny Media Technologies Inc., a Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»music-tech company that provides a platform, Play MPE, that artists and record labels use to get their songs in front of radio station program directors, music journalists, A&R (artists and repertoire) departments and other music industry

doyens and curators.

“I think smaller artists tend to think that Spotify is the way to go, when it really isn’t,” Vandenberg says. “If you get on the radio, that exposure is to the entire audience of the radio. You get on Spotify, then who knows who hears it?”

Cate Horsley agrees, and she has a unique vantage point, having worked both sides of the music business.

Horsley is not only the marketing manager for Play MPE, she is also a user – a singer-songwriter and leader of the band Chalcedony, and founder of her own independent record label, Aura Aurora Records. She has also worked with other record labels, as well as the artist management company S.L. Feldman and Associates.

Radio still matters, she says, adding it also pays better than streaming.

“These are still music industry gatekeepers, and if you can prove that you can get on the radio, that’s going to speak way more highly than like, ‘I paid this fake promo company to get me on Spotify playlists,’” Horsley says. “All that stuff can be so fake. You cannot fake a radio programmer adding your song to radio.”

Play MPE started out in the early days of the internet and dawn of the digital music era, when peer-to-peer file sharing platforms like Napster wreaked havoc on the music industry by enabling music piracy. Destiny Media developed technology that protected digital music files so that songs could be sent to record labels, radio stations and music journalists in a format that prevented them from being copied and pirated.

“The original idea of that technology was to counteract Napster for file sharing,” Vandenberg says. “It would lock your content – your music – to a device.”

Over the years, Play MPE’s massive catalogue of radio station program directors, music journalists and A&R departments became the company’s mainstay business, providing a music distribution service for record labels. Three of the world’s largest record labels – Warner, Sony and Universal – use Play MPE.

As the business evolved, Vandenberg says the company realized that smaller labels and independent artists just didn’t have the same capacity as big record labels, so Destiny Media Technologies began providing them access to the Play MPE platform as well.

An Indie country artist, for example, can use Play MPE to get his or her music into the hands of A&R departments, country radio stations and music journalists in the U.S. for about $850. That’s the most expensive offering, as the country music market in the U.S. is huge. Distribution lists for genres with smaller markets, like jazz or metal, are a lot cheaper.

But as Vandenberg notes, one of the first things an artist using the service wants to know is this: Did my song actually get played on the radio?

If it did, and if it got played often enough, and if the artist belongs to a performing rights organization (in Canada, that would be SOCAN), then he or she would get a royalty check, albeit several months later. But at present, that royalty cheque and any information on where the song may have received airplay can take a year or more to be delivered to the artist.

So, Destiny Media has developed a new platform called MusicMTR that will give artists more granular real-time data on radio play.

Until radio stations started broadcasting online, it was simply impossible to monitor every radio station in the country. Now, it’s possible.

“Now most radio stations duplicate their signal on the internet, so you can listen digitally,” Vandenberg says. “So we started developing this algorithm a couple of years ago to listen to radio stations digitally and then track what songs are being played by listening to an Internet signal.”

In July, MusicMTR was launched in beta in Canada only.

“Anybody who wants to see if their song’s played in Canada, we are listening to around 800 stations, and you can see when your song is played,” Vandenberg says.

Horsley says she believes radio tracking could become an important new tool that allows artists to see who is playing their music, and cultivate relationships with stations and DJs through social media. The platform could be used to find out which cities have stations playing an artist’s song or songs, perhaps leading an artist to decide to put that city on a tour itinerary.

“I used to know an old manager friend,” Horsley says. “She’s like, ‘You want to see where those little sparks are bursting into flames and you want to focus on those areas.’ With the radio tracking, that is concrete evidence of where things are popping up.”