British Columbia is known as a mineral-rich province.

But when it comes to determining where those deposits lie, it can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

Geoscience BC, an independent non-profit organization funded by the B.C. and federal government, has been trying to take some of mystery out of mineral exploration and for the past five years has been focused on a study of a large area of the Interior region of the province known as the Quesnel Terraine.

All the findings of the are publicly available and they provide geological evidence to help inform land-use decisions of mining companies, government organizations, Indigenous groups and communities and help create economic development opportunities.

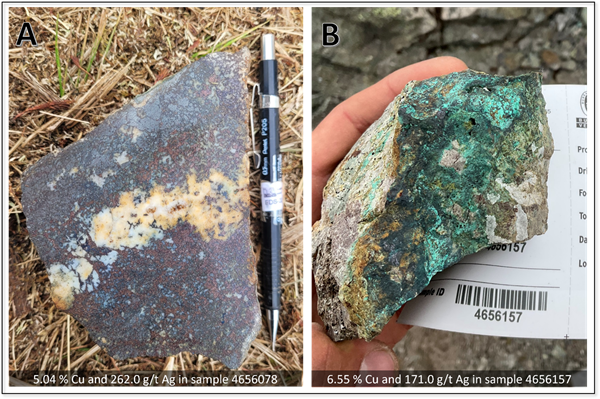

The latest research conducted by Wayne Jackaman of Noble Exploration and Dave Sacco of Palmer Environmental Consultants is based on analytical results of 1,500 new/archival samples collected around Williams Lake, Quesnel, Vanderhoof, Fort St. James and Mackenzie.

The 9,00 square-kilometre Quesnelia deposit belt covers the area on which Prince George sits. It stretches 1,500 kilometres from the U.S. border almost as far as Dease Lake in northwestern B.C. and is between 30 and 100 km wide. Samples taken from glacial till sediments left behind from the erosion of retreating glacial ice range from a few centimetres to hundreds of metres thick.

“Within this geological feature there’s this big gap between Mount Milligan in the north and Mount Polley and Gibraltar in the south - there are no mines in that terrain and that’s because people haven’t found copper and gold deposits in that area,” said Richard Truman, Geoscience BC vice-president of external relations.

“But the theory is that beneath that till left behind by the last ice age, which is very hard to see through, there may be other copper and gold deposits. The purpose of the program is to get an understanding of what might be in that area below the till.”

Advances in battery technology and the invention of portable backpack drills have given geologists new tools to obtain near-surface samples working in remote locations and Truman says that helped Jackaman and Sacco in their study.

“There’s been a lot of work in the area to try to understand what’s beneath the till, but this the most detailed and most up-to-date, most thorough work that’s been done,” said Truman. ”A lot of methods that are used for doing these sorts of things are developing really quickly.

“This is a huge area and we’re helping to focus mineral exploration so people know where to start looking.”

The project will be completed this year and a final report is expected in the summer.

The data obtained is available on the Geoscience BC website.