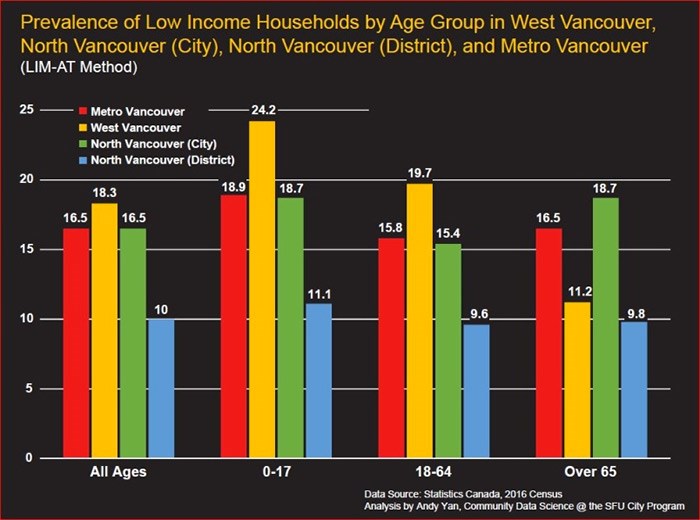

A chart created by Andy Yan shows the relative percentage of low-income households by age group, comparing West Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»to neighbouring communities. The analysis uses after-tax low-income thresholds from Statistics Canada. graphic supplied Andy Yan

A chart created by Andy Yan shows the relative percentage of low-income households by age group, comparing West Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»to neighbouring communities. The analysis uses after-tax low-income thresholds from Statistics Canada. graphic supplied Andy Yan

The affluent community of West Vancouver, where average home prices hover at $3 million, has one of the highest rates of people with âlow incomeâ in Metro Vancouver. At least on paper.

That surprising piece of information comes from an analysis of recently released Statistics Canada income figures by Andy Yan, director of Simon Fraser Universityâs City Program.

According to Yanâs analysis, there is a higher percentage of âlow incomeâ households in West Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»â more than 18 per cent â than in Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»as a whole, where about 16.5 per cent of households are low income.

In certain areas of West Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»â like Chartwell and Ambleside â that percentage of âlow incomeâ families climbs even higher, to 25 and 33 per cent of all households.

The number of people living in low income households has also risen dramatically in the last decade in West Vancouver, shooting up by 37 per cent, an increase over double that seen in Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»as a whole and about 10 times the rate of change in the neighbouring District of North Vancouver, according to Yanâs analysis.

But are up to a third of households living in mansions worth millions really scraping by on meagre poverty-line incomes?

Yan and other analysts say likely not.

More likely, they say, the figures reflect the limited way that income statistics capture âwealth,â particularly in the case of well-to-do immigrant families whose wealth is often generated outside the country.

âIt led to a really interesting discussion,â said Yan, of the numbers heâs come up with.

While rates of poverty are definitely up in suburban areas these days, seeing such high rates of low income in West Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»just doesnât appear accurate in the face of âall that real estate wealth and watching that Lamborghini buzz by you on the Lions Gate Bridge,â he said. âIt does not compute.â

Daniel Hiebert, a University of British Columbia geography professor who has studied international migration and its impact on the housing market, said such numbers only make sense in the context that âwealth and income are separate things and we record and tax income, but leave wealth alone in Canada.â

West Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»has some similar patterns to Richmond in this regard, says Hiebert, where immigrants rely on wealth from overseas to buy into the local real estate market.

âDoes this mean people are poor?â he asks. âNo. It means weâre not tracking an essential component of economic well-being: wealth.â

There is also the possibility of undeclared income, whether that is acquired in Canada or abroad, he adds.

For instance, gifts of money among family members donât have to be declared, he said.

Richard Kurland, an immigration lawyer and policy analyst, said areas like West Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»have been on his radar for the combination of low taxes paid despite stratospheric real estate sales. The issue lies in households whose members maintain they are residents of Canada for the purposes of being exempted from foreign buyersâ or capital gains tax in the real estate market yet donât disclose or pay taxes on the global income which allows them to buy into that market, said Kurland.

â. . . some of Canadaâs wealthiest families have all the benefits of being Canadian, but may legally avoid paying Canadian income tax, even though they are living in Canada part time, because they are entitled to be ânon-residents of Canadaâ for income tax purposes,â he said.

Kurland said heâd like to see changes made to the tax system that would see high property taxes levied on millionaire mansions â which could then be lowered for those declaring certain levels of taxable household income.

âItâs a social justice issue,â he said. âMillionaire families enjoy a millionaire lifestyle without contributing a millionaire share of taxes.â

Read more from the