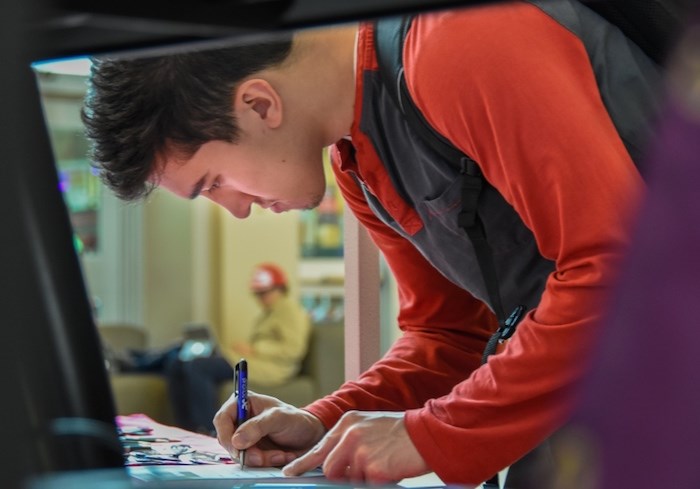

Douglas College student Jonah Roesler, 22, signs a pledge to vote in the upcoming federal election. Photo by Stefan Labbé/Tri-City News

Douglas College student Jonah Roesler, 22, signs a pledge to vote in the upcoming federal election. Photo by Stefan Labbé/Tri-City News

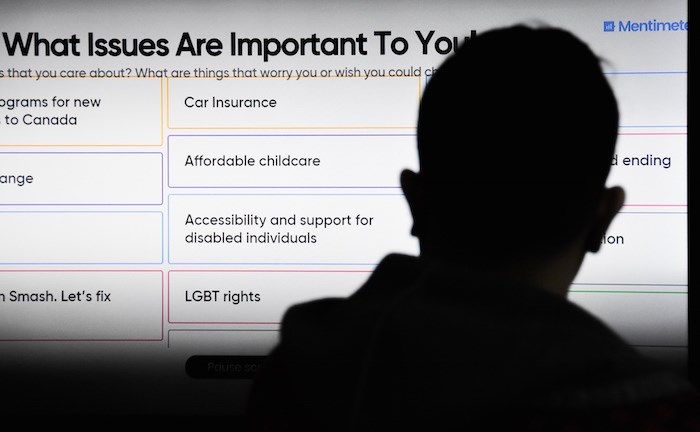

Students drift in and out of the commons area at Douglas College, some queue for coffee at Tim Hortons, others cross the floor, attracted by a digital carousel flipping through some of the major public policy challenges today: climate change, affordable child care, housing.

The big screen was brought in for students to share their biggest concerns. Itâs a talking point and a reminder that the election is around the corner. If that wasnât enough, on the table, pamphlets, pins and pens emblazoned with âI will voteâ litter the table.

Itâs all part of a growing get-out-the-vote movement, which, for this election cycle, was re-ignited this month in a campaign launched by the BC Federation of Students (BCFS), an organization that represents about 170,000 students in 14 universities and colleges.

The âOur Time is Nowâ campaign uses paper and online pledges to improve voter turnout among young British Columbians. Photo by Stefan LabbĂ©/Tri-City News

The âOur Time is Nowâ campaign uses paper and online pledges to improve voter turnout among young British Columbians. Photo by Stefan LabbĂ©/Tri-City News

At the heart of theÌę, young people pledge to vote, either on paper, guided by 100 volunteers across the province or online. Once they sign the pledge, prospective voters receive information on how, where and when to vote, as well as party platforms and digital updates throughout the election campaign.

âWe don't tell people who to vote for and we're not talking about any issues during this period. It's simply getting people the information they need to go out and vote,â said Janelle Davies, an organizer for BCFS.

As demographics lean towards a younger electorate, currying votes from youth has become an increasingly important factor on the road to electoral victory.

Voter participation among young people spiked in the 2015 federal election, with Elections Canada data showing that 57% of voters aged 18 to 24 cast a ballot, an increase of 18% from the 39% recorded in the 2011 election. That's the largest increase ever recorded by the elections agency since it began reporting demographic data.

Add that to the high voter turnout in the 2017 B.C. provincial election and a demographic shift that â for the first time in 40 years â positions young Canadians as the largest voting bloc in a federal election, and BCFS chair Tanysha Klassen says the message is clear: Young Canadians canât be ignored.

âThere are clear and obvious reasons for higher voter participation amongst young millennials across western democracies in the past three to four years,â said Klassen. âOur job prospects are tenuous, housing and education costs are through the roof, and the planet is burning. We donât have the luxury of sitting on the sidelines. Weâre being politicized by the conditions of our time.â

For Douglas College student Mitchel Gadayo, the last federal election was the first time he had voted. At the time, he was a first-year student at the schoolâs Coquitlam campus. Today, he has risen through the ranks of the student union to become director of external relations, a position that puts him in charge of this yearâs voting campaign.

In the four years since the last federal election, the students walking the halls of Douglas College have changed, he said.

âWe see this trend of being more educated, more woke to issues that matter to them,â said Gadayo. âThe conversations that weâre having are, âWhat can we do about climate change? What can we do about affordability?'

Douglas College student volunteer Jerson Sabio, 20, looks on as a list of student-generated voting issues ticks across a screen at Coquitlamâs Douglas College. Photo by Stefan LabbĂ©/Tri-City News

Douglas College student volunteer Jerson Sabio, 20, looks on as a list of student-generated voting issues ticks across a screen at Coquitlamâs Douglas College. Photo by Stefan LabbĂ©/Tri-City News

âNot everyone is a policy junky or has the language but they seem to be informed, understand these things are happening.â

Student associations have become one of the most powerful vehicles to get young voters to the ballot box. Thatâs partly because of simple logistics: Itâs easier to find and convince 18- to 24-year-old students to vote when theyâre concentrated on a campus like Douglas', said Paul Kershaw, the founder of the research and advocacy groupÌę.Ìę

âWeâre turning the tide on the idea that politics is a punchline of a joke rather than a really important process we need to participate in,â he toldÌęThe Tri-City News.

Kershaw said data does not support the narrative that discounts young people as lazy, whiney, entitled consumerists and, in politics, apathetic; rather, Kershaw said, the baby boomer generation turned off the younger generations from electoral politics by socializing them to view politics as something that wonât affect their lives.

Party politics hasnât done any better. Kershaw points to the tendency of political parties to devote a massive chunk of their spending promises on health care and old age security, investments that disproportionately benefit an older demographic. By contrast, party platforms have traditionally set aside modest amounts of money to make life more affordable â through investments in things like education and childcare â or tackling climate change.

Kershaw said that makes younger people less likely to engage with electoral politics and perpetuates a vicious cycle of voter alienation â young people would sooner scrawl a message on a protest placard than fill out a voter registration card.

But that changed last federal election and part of the Liberals' success was because of an uptick in the turnout of young people, who disproportionally voted for them.

The BCFS claims young voter turnout in the last federal and provincial elections provides enough evidence of a sea-change in voter demographics.

This time around, other political parties seem to be getting the message; so far, a lot of lip service has been paid to improving affordability for Canadians.

Whether that will motivate young voters to come out again in the same way as they did in 2015 is something Kershaw is watching carefully.

âWe've only got the 2015 federal election as a national data point that shows a reversal in that trend,â he said. âBut if they do [come out], absolutely a trend is emerging.â