If British Columbians opt for a change in how they elect governments, Victoria’s work kicks into high gear to write new legislation and examine riding boundaries before the 2021 provincial election.

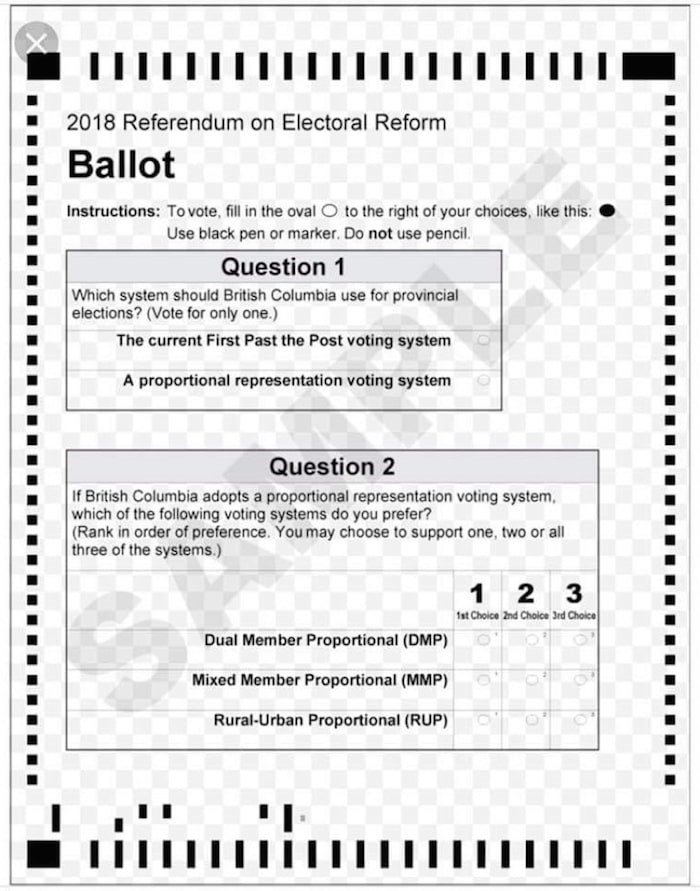

Voters may choose to keep the existing first-past-the-post (FPTP) system or opt for a new proportional representation (PR) system that balances seats in the Legislature with the popular vote. On the ballot are three PR options — Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP), Dual Member Proportional (DMP) and Rural-Urban Proportional (RUP) — which will result in varying legislation and expected outcomes.

In October, British Columbians will vote via a mail-in ballot on whether to adopt a proportional representation electoral system. Photo iStock

In October, British Columbians will vote via a mail-in ballot on whether to adopt a proportional representation electoral system. Photo iStock

It won’t be the end of referendums, though. If PR is chosen after the Nov. 30 mail-in deadline, there will be another vote in 2026 to confirm the decision after two elections.

What else would happen?

An all-party committee would need to be struck to make recommendations for the implementation of the chosen voting system.

University of B.C. political scientist Richard Johnston said—as many on the No-PR side have—that several issues remain outstanding: the exact district boundaries, how many districts and regions there will be, and whether to have open or closed lists of candidates. The number and complexity of such issues depends upon the specific voting system.

It is known that all three PR systems will have 87-95 seats. But the committee will also need to decide on seat “overhang,” which is when one party happens to win more seats in local ridings than the popular vote would allow. In such a case seats could be added.

That committee would report its findings no later than March 31, 2019.

Legislation would be drafted and debated to establish the new voting system.

As well, an independent Electoral Boundaries Commission would be required to recommend new electoral boundaries following guidance from the committee, a process that is expected to take until fall 2019.

After receiving the final boundaries, Elections BC would go to work on examining the nuts and bolts and making it work.

Deputy chief electoral officer Nola Western said an estimated 14 months would be needed to put things in place for the first election under PR.

“There’ll have to be an Electoral Boundaries Commission and quite a bit of work on our part to figure out how the new voting system will work,” Western said.

British Columbians would then have two elections and governments to test-drive the system. A second referendum would be held in 2026 to decide if the new system should be kept or discarded.

If PR is discarded in that vote, B.C. returns to the current system.

Former Social Credit Party cabinet member and past BC Reform Party leader Jack Weisgerber rejects the idea that a 2026 referendum can be promised.

“It’s not legislatively possible for the government to bind a future government to a decision,” Weisgerber said.

Attorney General David Eby disagreed. He said governments are legally bound to follow earlier decisions. But, “certainly a critique. . .that a future government could repeal the legislation is true.”

A report last May to Eby identifies the need for further discussion on the details of which PR system is chosen. The number and complexity of those details depends upon the specific voting system.

The appendices describing the proposed PR voting systems include a list of design details that would require decision post-referendum. Those considerations include numbers of MLAs and what form of party lists might be used to determine representation under mixed-member PR where voters get two votes—one to choose representative for their single-seat constituency, and one for a political party.