For the past few years I've been volunteering for the , a Vancouver-based charity that works to bring our salmon back "stream by stream" in British Columbia. I've sat on the of their DFO salmon stamp artwork competition, on the for their annual Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»fundraising gala, I've facilitated V.I.A. sponsoring their and I've helped with other efforts wherever I can. To say that I love what they do would be a major understatement; these are truly my people.

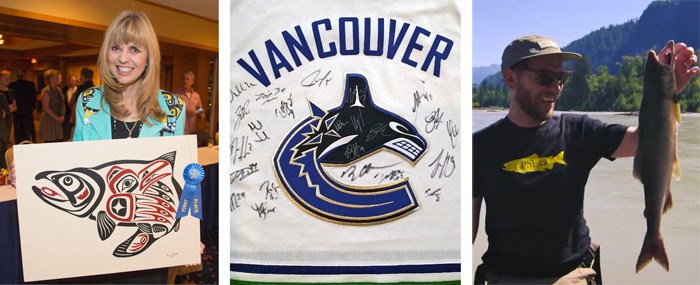

L to R: April White and her winning salmon stamp art, team signed Canucks jersey for the annual gala, promoting the Pink Salmon Festival

L to R: April White and her winning salmon stamp art, team signed Canucks jersey for the annual gala, promoting the Pink Salmon Festival

I'm incredibly happy to announce that I've now come on board with the foundation in an official capacity, working as a roving reporter and social media advisor. I'll be digging into their , the salmon stamp, and I'll be showcasing projects they fund, heading out to meet with different volunteer groups that they support. One of the things that stands out about the PSF to me (aside from them helping salmon, a cause near to my heart) is the fact that for every dollar they raise from donations, the groups that they grant that money to turn it into six dollars. 117 streamkeeping groups received a total of $1.53m from them last year to help their hatchery and rehabilitation projects, built almost entirely off of volunteer work. These volunteers are the true unsung heroes of salmon in BC and I'm honoured to be able to help tell their stories, here on our blog and through the PSF's social channels.

For my first trip with the PSF I headed to Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island, and to the 's hatchery in Oceanside. Volunteers Ken Traynor, Jack Gillen and Gord Lipke met me on a Saturday morning and we walked a few hundred yards up a dirt road from the gated entrance. The hatchery is located on crown land that they've been allotted a long term lease for, and this road up to it also connects to a trail system that people in the area use to explore nature.

On our way to the hatchery

On our way to the hatchery

They showed me around their hatchery building shown below. Right now they've got 1,250,000 Pink salmon in those big vats behind them.

The salmon are almost out of the "alevin" stage, which is the stage when they've still got a little egg sack attached to them. They swim around inside these things below, which are supposed to be like gravel in the wild.

This artificial gravel fills up the tanks. The one below has 250,000 tiny salmon swimming in it!

As I mentioned, they're almost through their alevin stage. Once they're done, that pink stripe on the bottom will completely disappear.

Once they get out of that stage, they naturally swim to the top of the artificial gravel and make their way up and out. They head towards this drain where they then swim directly into Nile Creek, which is about 20 metres from the building. They then make their way down to the ocean where they fully mature, then they return to this exact spot to spawn.

They've seen great returns on this river, but that wasn't always the case. The salmon were struggling so in 1999 they got funding to create a side channel for the fish to spawn in. It has a much slower flow and while not all of the fish choose to go up it when they return to spawn, most do.

On this particular day they noticed that the channel was abnormally low for some reason, so we walked a few hundred yards up to its source to see what the problem was. Ken quickly concluded that there was a bunch of rubbish obstructing the intake of water further up, so he manually turned off the flow.

When we walked up to the intake above he pointed out the air that was escaping as the tube filled up with water after closing it, effectively spitting out all the stuff that was clogging it. That pipe you see under the water there connects about 50 yards down to the slower moving channel and after a few minutes it had been flushed so we returned to the valve and opened it up again, and the flow went back to normal. It's things like this that the volunteers return to the hatchery every day to take care of.

One of the other daily duties is calculating the Accumulated Thermal Units (or ATUs) of the water. This is a method used to predict when the salmon eggs will hatch, and then track their progress through the alevin stage. is an explanation of how it works - it's fairly simple and basically involves adding up the total amount of temperature the eggs have been exposed to over time.

Ken, Jack and Gord are just 3 of many volunteers who work on Nile Creek (), and there are thousands more dedicated folks like them at work on other projects in British Columbia. I look forward to introducing you to more of them!

Ken Traynor, Jack Gillen and Gord Lipke, outside the Nile Creek Hatchery

Ken Traynor, Jack Gillen and Gord Lipke, outside the Nile Creek Hatchery