The federal government on Tuesday condoned and approved B.C.’s hasty retreat from decriminalizing drug use, so the surrender is now official and complete.

You wouldn’t know it from the B.C. government’s response, which was to suggest that it allows B.C. to “take action” in the continuing battle to find some way of making a difference in the opioid crisis.

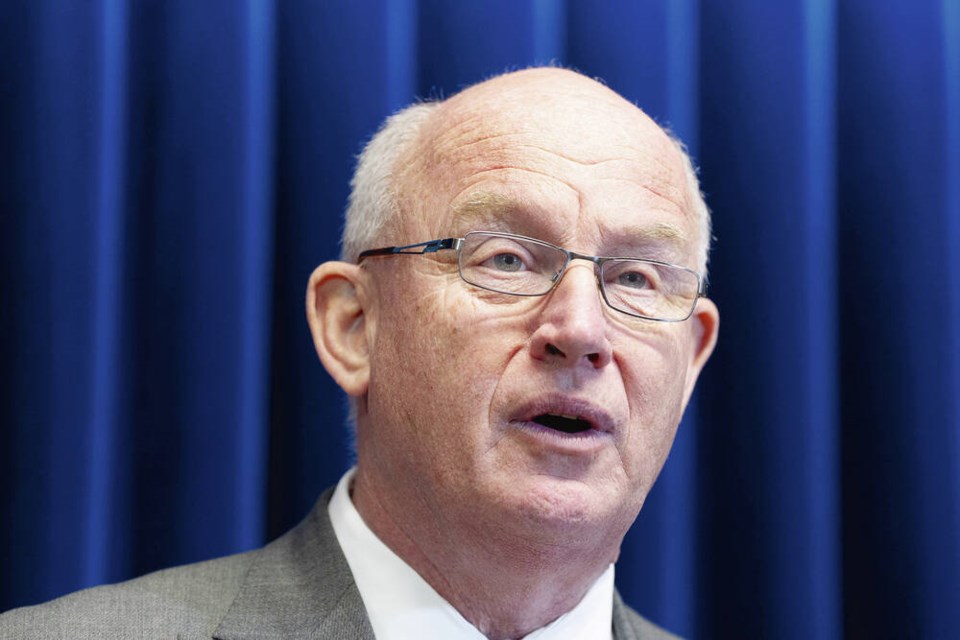

Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth said “we took action in the fall” when the NDP government introduced a bill to outlaw drug use near play areas, parks and most public spaces.

That was just eight months into the pilot project that allowed exactly that alarming behaviour. An injunction against the bill temporarily cancelled that effort, so the government applied to Health Canada to rescind decriminalization in all public areas.

It was granted on Tuesday, so Farnworth announced “we’re taking action today,” by reverting back to the old total prohibition against public drug use.

Taking action implies moving forward. But they are going backward and capitulating on decriminalization, without explicitly saying as much.

“Today, I am writing a letter to police to inform them that these changes are now in effect,” Farnworth said.

People addicted to hard drugs will not be charged or prosecuted for using in private homes, designated shelters or treatment centres. Those using drugs (mostly by smoking) in restaurants and public spaces will now be subject to the law again, but, he said, the guidance to police is “to only arrest for simple possession … in exceptional circumstances.”

If they are not listening or being aggressive, “police have the ability to seize those drugs.”

That means the standing orders now in B.C. are pretty much exactly what they were in the years before the decriminalization experiment started, on Jan. 31, 2023. Police used discretion to not charge for possession of small amounts for years, and that was made official policy in 2017.

The goal of that standard operating procedure was to reassure people they could call for help in an emergency and not get busted.

Farnworth said police have made it clear they don’t want to criminalize people, “what they wanted is the ability or the tools to be able to move people along.”

Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside said: “As we take action to address public drug use, we’re also continuing to ensure that we treat addiction as a public-health issue, not a criminal-justice one.”

That harm reduction mantra didn’t hold up well at ground level when decriminalization got underway. Dozens of local councils started crafting their own bylaws against public use in response to citizens’ objections to the practice.

Whiteside said: “British Columbians have been very clear they need to feel safe in their communities.

“I have been clear from the start that the intention of decriminalization was never about providing space for unfettered public drug use.”

But that’s exactly what developed, as frightening stories from playgrounds and restaurants and hospitals emerged.

Whiteside anticipates seeing a reduction in the number of people experiencing that from now on.

Opposition B.C. United critic Elenore Sturko, a former Mountie with deep experience in drug crime, said the big problem remains. The ability for police to “move drug users on” has been restored, but move them on to what?

Most police detachments don’t have rehabilitation or treatment centres nearby, she said. “For a lot of communities, this is simply putting the problem back into the laps of police with no way to guide people to the help that they need.”

Decriminalization never had a chance of working, she said.

The coroner’s monthly tally of overdose deaths was released a few hours before Farnworth and Whiteside spoke. It counted 192 fatalities in March (down 11 per cent from March of last year) and at least 572 in the first three months of the year.

Overdose deaths are higher than homicides, suicides, accidents and natural causes combined.

The day before decriminalization took effect 14 months ago, officials said it was going to be a vital step to get more people connected to services. It was going to reduce the stigma and reduce harm.

It’s hard to see today that it accomplished much of anything.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]