My first experience with book banning came when, at the age of 15, I somewhat precociously read Irish novelist James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Not an easy read, but I had been told that the main character, Stephen Dedalus, questioned and rebelled against the Catholic and Irish conventions under which he had grown up.

At 15, I thought that I could identify with that, and so I struggled through 384 pages of the Penguin Classics edition.

The novel, despite warnings by some self-appointed critics, did not cause me to become hedonistic, deeply religious or even a confirmed aesthete.

Next step was to go to the local library to look for another Joyce novel. Ulysses sounded promising and this time the literary critics spoke of puns, parodies and broad humour.

Sounded like my kind of novel.

“No — this is not a book or you,” said the librarian in a voice that would brook no argument.

Maybe it was about sex, I wondered — an emerging but confusing topic for a 15-year-old.

So I went home and secretly borrowed Grace Metalious’ Peyton Place from my parents’ library to see if there was anything in that novel that would confirm or refute some of the rumours I was hearing on the playground of my all-boys high school.

I found some stuff about “heaving bosoms,” which made no sense to me at all at the time, so it was back to Dickens and William Golding.

What brought all this to mind is the fact that last week was Banned Books Week in the U.S., an annual awareness campaign promoted by both the American Library Association and Amnesty International that draws attention to banned and challenged books in that country.

The attempt to ban books from a school or public library is usually initiated by an individual, association or organization that demands that a school district, institution, retailer or publisher remove a book that doesn’t align with their beliefs.

Objections about content start with overt sexuality and move on through a quagmire of “offenses,” including other religious viewpoints (26%), LGBTQ content (23.5%), violence (19%), racism (16.5%) and use of illegal substances (12.5%), any of which is bound to offend somebody somewhere.

Banned and challenged books in some school and even public libraries in the U.S. have included The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger, The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, and, of course, Ulysses by James Joyce.

In fact, Ulysses was the subject of a U.S. obscenity trial in 1921 and its publishers were fined $50 and banned from publishing it. The ban was not lifted until 1934.

Even in Canada, a free country by world standards, books and magazines are sometimes banned at the border. Schools and libraries are regularly asked to remove books and magazines from their shelves.

Freedom to Read Week in Canada is an annual event organized by the Book and Periodical Council, the umbrella organization for Canadian associations involved with the writing, editing, translating, publishing, producing, distributing, lending, marketing, reading and selling of written words.

In a new twist to my column from December 2022 about reasons for removing books from school libraries, Ontario’s Peel District School Board last month rolled out a process that caused some schools in the area to remove books from the shelves solely based on publication date, according to a CBC report.

Under what was called an “equity-based book weeding process,” all books published before 2008 were removed.

The Peel District School Board’s book “weeding” process targeted Harry Potter, The Hunger Games and Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, a 1977 novel by award-winning young-adult author Mildred D. Taylor about the struggles of African Americans in 1930s-era Mississippi.

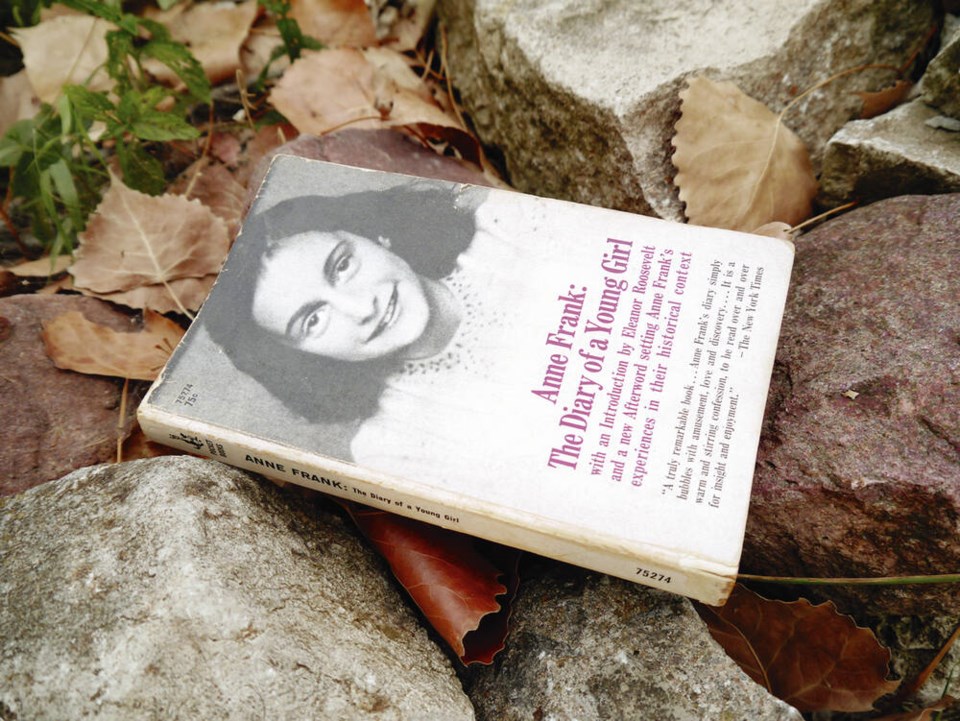

Also among books removed was The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank.

The Ontario education minister immediately called a halt to the process.

The school board directive that led to the removal of books from shelves read: “The Board shall evaluate books, media and all other resources currently in use for teaching and learning English, History and Social Sciences for the purpose of utilizing resources that are inclusive and culturally responsive, relevant and reflective of students, and the Board’s broad school communities.”

There was no clarification of who would determine what that might mean. Or why 2008 was selected.

In a recording viewed by CBC, school board trustee Karla Bailey said during a committee meeting in May: “When you talk to the librarian in the library, the books are being weeded by the date, no other criteria.”

“No other criteria” eh? Hmmmm…

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]