“COVID is over.” “Get on with life.” “Imagine still being afraid of a cold.”

If you’ve tossed out one of those off-handed comments, either on social media or in real life, then this is for you. I need you to listen. I need you to understand what it means for me, and for countless thousands of others, when we hear you dismiss this virus so casually.

Tell me it’s over, and I’ll tell you how it feels to know that, for my family, it will never be over.

COVID irrevocably changed our lives when it found my Dad, despite all the caution he exercised, and left its legacy in the form of congestive heart failure.

Dad died July 14. He was 82.

I’m sure the “COVID is over” crowd would be happy to chime in to tell everyone COVID deaths don’t count if the person who died was old. As if whatever time was left in their lives — one year or five or 10 or 20 — had less value than whatever time is left in mine, or yours. As if my father’s eight decades of love-filled, faith-filled, compassion-filled life count for nothing.

My Dad mattered. His life mattered.

*

His name was Ronald Pius MacLellan. He was born in Buchans, Newfoundland, son of a coal miner from the Codroy Valley. He was the eldest of seven children in a family that moved first to Cape Breton and then to Northeastern Ontario, following the mines.

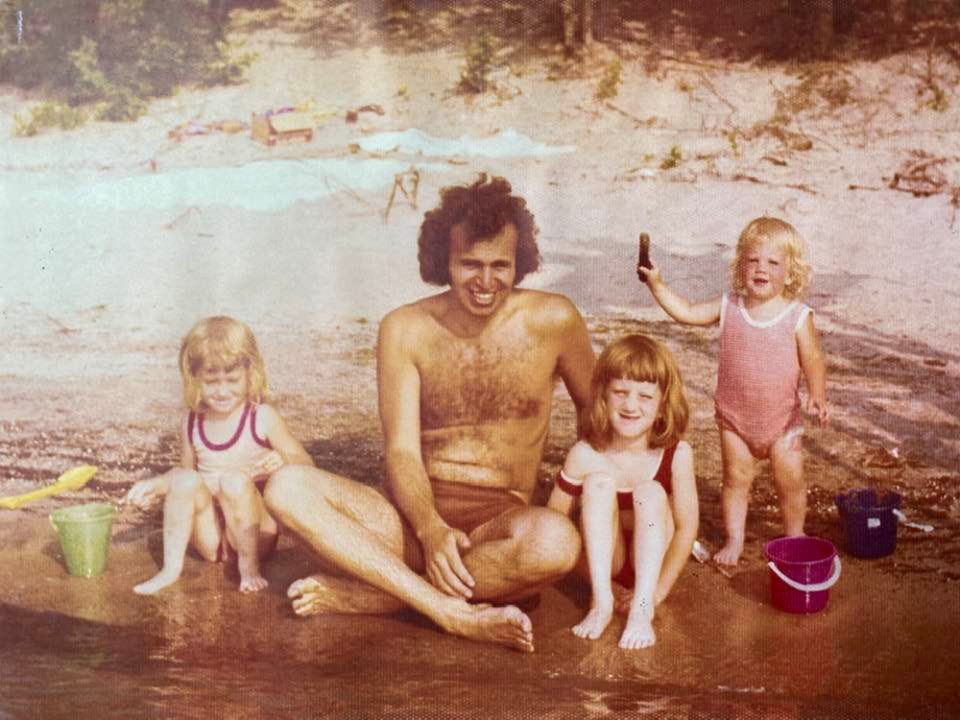

He became a teacher, a career path that took him to the small farming community of Phelpston, Ont., where he joined the church choir and met a fellow teacher who happened to be the choir director’s daughter. They later married and had three girls.

He was a steadfast Roman Catholic, becoming an ordained deacon in 1983. His was a faith of joy and hope; he was never about sin and shame, but about compassion and service and social justice, long before such a concept became mainstream.

He was a singer, a reader, a writer, an absent-minded professor who could get lost in philosophy and theology for hours but whose grasp of the practical was questionable. He’d never have been on time for anything if it hadn’t been for Mom.

He loved his garden, his God and his family — not necessarily in that order — and his one granddaughter was the apple of his eye. She, in turn, loved “silly Grandpa”; one of the worst parts of the pandemic, for her, was not having her grandparents fly from Ontario to B.C. for regular visits.

Tell me COVID is over, and I’ll tell you how it feels to watch your child’s heart break.

*

Tell me it’s over, and I’ll tell you about grasping the smooth, cool surface of the bars at the sides of Dad’s casket. I’ll tell you how it felt to walk alongside my sisters, my husband, my cousin and my daughter to carry that casket through a Knights of Columbus honour guard into his funeral mass.

I’ll tell you about my fierce and overwhelming pride in the just-turned-10-year-old who walked in front of me, determined to do Grandpa proud. I’ll tell you how she seemed to grow up in an instant, wearing her first pair of heeled sandals and a brand-new blue dress with flowers, chosen to reflect Grandpa’s love of his garden. I’ll tell you how one shy child faced down her anxiety with a deep breath and a straight back and walked with grace down the aisle of the church while hundreds of strangers watched.

I’ll tell you how it felt to accompany my father one final time into the church where I was baptized, where I attended mass with my family every Sunday as a child, where I sang in folk choir at Saturday night mass as a teenager.

I’ll tell you how it felt to try so hard to sing for him when the musicians opened with one of his favourite hymns. I’ll tell you how my throat closed when I couldn’t get past the memory of sitting at the piano at home, singing Here I Am, Lord with my Dad. I’ll tell you how my husband’s voice broke as he stood next to me and sang out, and how the wool of his suit jacket felt soft against my skin as I clung to him.

I’ll tell you about the warm weight of my daughter’s head on my shoulder and the heat of her tears streaking down my bare arm.

I’ll tell you about the blur of solemn faces, the weight of the communal sadness of his brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews, in-laws, neighbours, colleagues, parishioners, friends.

I’ll tell you how images from a formal, ritual farewell can sear themselves into your memory with the white-hot pain of a branding iron. How it feels equal parts healing and heartbreaking when you wake up in the darkness replaying those images, unable to stop the film reel from unrolling even if you wanted it to.

*

I may smile, or even laugh, and you may wonder why. But I’ll tell you how sadness can live side by side with joy. How a trip to a funeral can co-exist alongside an impromptu family vacation.

I’ll tell you about watching my daughter exclaiming with amazement at the vast expanse of Wasaga Beach, astounded by its soft, fine sand and the way Lake Huron looks like an ocean.

I’ll tell you how it feels to see her trusting in the solidity of her dad as she plunges into the blue waters of Georgian Bay with him at her side, leaping into waves with abandon. I’ll tell you how I plunge, too, because if I get my face wet then my tears will blend in and it won’t matter if my memory replays our childhood trips to Wasaga Beach and the way I used to play in the waves with my own Dad and no one will see if I can’t stop the thought that I’ll never be back here with him again and it all seems impossible and overwhelming and surreal yet here I am laughing and leaping and shrieking with my daughter.

Funny thing about tears. Sometimes you can’t even tell they’re falling, except for the salt on your skin.

*

I’ll tell you how grief follows you around like a soft, fine sand of its own, seeping into your skin and threatening to spill out of unexpected places at inconvenient times.

When you order a drink at Starbucks and remember how your gentle, good-natured father was always humorously grumpy about pretentious coffee orders.

When you open Facebook to be accosted by today’s memories, which most days include a comment from him about something on your feed that caught his eye — a post about a choir concert, a photo of his granddaughter or, in today’s case, a piece of your own writing that he loved so much he wanted to borrow from it for a homily at church.

I’ll tell you how this soft, fine, almost-tangible thing that is grief seeps out in the form of tears when your co-worker comes over to your cubicle and asks, “How are you doing?”, and you know she actually wants to know.

Or when your daughter digs into the basket of barely touched stuffed toys to pull out Squeaky Lion, the tiny toy she always wielded as a wake-up call for Grandpa when he’d stay in our basement bedroom. When the thought that he’ll never be back to stay in that bedroom hits you like a sucker punch and knocks the wind out of you.

*

Tell me COVID is over, and I’ll tell you about the people who have been left bereft by his absence.

I’ll tell you about my Mom. My indomitable, unstoppable Mom, left without her life’s partner after nearly 55 years. What becomes of the practical, pragmatic half of a partnership when she no longer has an absent-minded dreamer to look after?

I’ll tell you about my sisters, strong and kind and intelligent and fierce and compassionate; in so many ways like Dad and in so many others like Mom. Like me, they find themselves suddenly halfway to orphaned, feeling the immense weight of the loss of one-half of the duo that has steered our family for the entirety of our lives.

And I’ll tell you about me. I’ll tell you about sitting at my desk on a Friday afternoon, crying in the newsroom because that’s a thing I do now. I’ll tell you about second-guessing the idea of ever sharing this. I’ll tell you about deciding to share it anyway.

I’ll tell you about starting to write my own grief story. I’ll tell you why I beat down the part of me that says it’s selfish to make this about me at all: because I know that we need to share our grief stories with each other, the same way we need to share all our stories. And a teller of stories is who I am. It’s who Dad helped me to become.

*

Tell me COVID is over, and I’ll tell you this story, because the world needs all the stories it can get right now.

Grief is an inescapable part of being human. But what of the grief that accompanies a mass event on the scale of a global pandemic? The past few years have left the world staggering under the weight of losses so enormous that no part of the planet has been left untouched.

COVID-19 has claimed more than 43,000 lives in Canada alone, more than 6.4 million around the globe. (And that’s only the official count, which lets out many people with similar stories to my own Dad, who may not have died directly of COVID but who would still be alive had they not contracted the virus.)

That’s 6.4 million lives, multiplied by all the people whose lives intersected with theirs and who are now writing grief stories of their own.

How does a world bear the weight of such sadness without collapsing in on itself?

How do I?

Such are the questions that haunt my sleep. Such are the questions that make me want to run through the streets screaming that everything is different now and shouting that it’s impossible for life to continue as it always has and asking why everyone else is just carrying on and acting like things are normal when they are so obviously clearly evidently completely and utterly not.

Such is grief.

*

This grief story is mine. If you, too, are living your own, then I hope you have found some solace in the shared stories of others and in the memories of your loved one; that you, too, can hold on to love and compassion and hope even while weeping at your desk or in the dark.

If you have been fortunate enough to escape grief, then my wish for you is that your story continues to be a happy one.

If you still insist upon dismissing my reality, then I will remember this truth: Dad would have found a way to meet your skepticism with compassion and to face down your contempt with grace. I will try to be as compassionate, as grace-filled, as hopeful as he was.

I will fail. But I will get up. I will brush off the sand. And I will keep crying and laughing and remembering and living and loving because what is else there to do?

*

All of this.

This is what I will tell you if you tell me that COVID is over.

Follow Julie MacLellan on Twitter .

Email Julie, [email protected]