When NDP leadership candidate David Eby proposed that those who repeatedly overdose might need involuntary treatment rather than rapid discharge from hospital to risk overdose death again, he was roundly criticized by former colleagues at the B.C. Civil Liberties Association.

His comments were termed “misleading, immoral and reckless.” It was asserted that “all evidence is clear that involuntary drug treatment can cause great harm — even death — and does not save lives.”

As doctors who treat youth with life-threatening substance-use disorders, known as SUD, we think that the evidence needs a fresh look. The paper most often cited by opponents of involuntary treatment is best viewed as a study of incarceration of adults in prisons in Asia and is not relevant to B.C.

While it is correct that enforced abstinence without the provision of opioid agonist therapy is dangerous, this approach is not being proposed. There is, however, relevant evidence to support time limited involuntary treatment when it incorporates opioid agonist therapy and harm reduction.

In a Norwegian study of the efficacy of involuntary treatment, the authors concluded that while “voluntary treatment for SUD generally yielded better outcomes, nevertheless, we also found improved outcomes for compulsory admission patients.

“It is important to keep in mind that in reality, the alternative to compulsory treatment is no treatment [and] outcomes for compulsory treatment support continuation of compulsory treatment.”

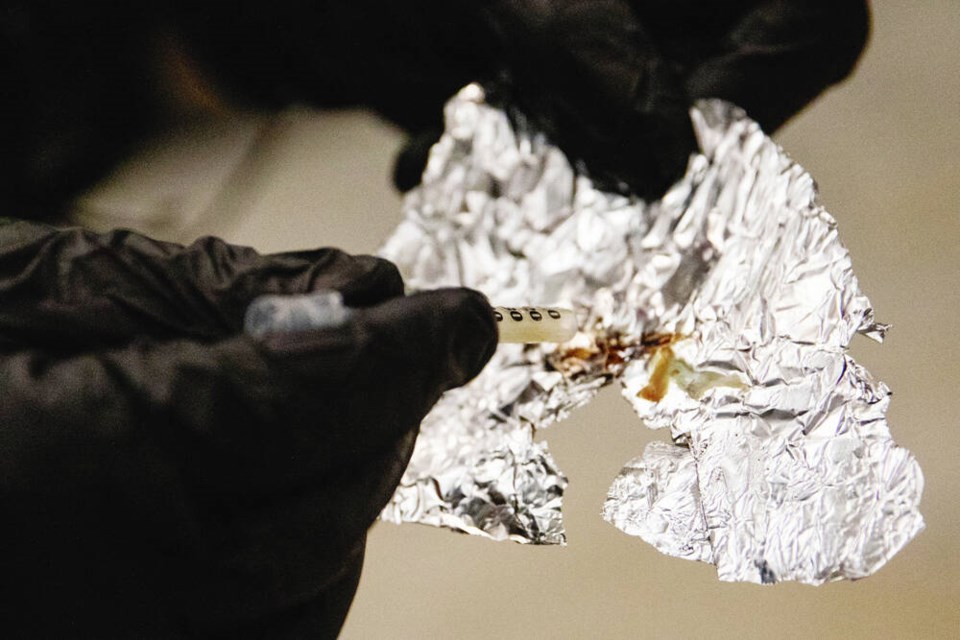

In April 2016, B.C.’s Chief Public Health Office declared a public health emergency in response to the nearly 1,000 deaths due to illicit drug overdoses that occurred in the previous year.

The yearly death toll has continued to climb, with more than 1,000 fatalities in the first six months of 2022. Overdose is now the leading cause of death for adolescents in B.C.

Current approaches are ineffective and our dogma must be questioned. Novel approaches are needed, including the full range of prevention and early intervention, harm reduction, safe supply and a consideration of hospital admission in the most rare and extreme cases involving children.

When a youth has a life-threatening overdose, it takes days for cognition to improve sufficiently for them to have the capacity to understand and appreciate, refuse or consent to treatment.

Most have serious mental health conditions; many are suicidal or at best indifferent to death. They are at high risk of a subsequent fatal overdose.

Yet current practice is to assume that only a few hours after overdose reversal, they are capable of sound reasoning and to discharge them. Usually follow-up is uncertain and guardians not notified.

In contrast, youth with mental health disorders who suffer non-illicit drug overdoses are invariably admitted, receive full psychiatric evaluation, and not discharged until clearly safe to do so. Youth with illicit drug overdoses deserve the same compassionate and comprehensive standard of care.

A brief involuntary admission for youth with a life-threatening illicit drug overdose provides a pause in a dangerous pattern of drug use.

It allows for cognitive clearing to permit a mental health review, for a youth to capably consider treatment options and for opioid agonist therapy to be effectively initiated. Connections to community resources can be re-established. If treatment is refused, the adolescent can be counselled, equipped for harm reduction and discharged.

This novel approach can save lives.

Eby should be congratulated, not castigated, for the fact that his position has evolved. More of us could learn from the famous British economist John Maynard Keynes who, when disapprovingly asked by a reporter why he changed his view on an important matter, replied: “When the facts change, I change my mind — what do you do, sir?”

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]