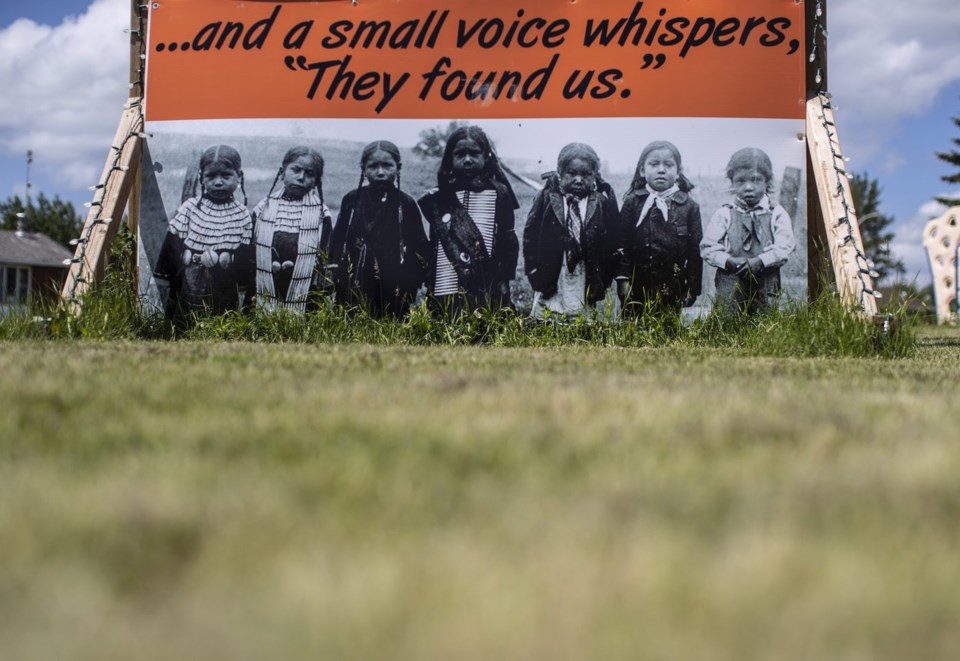

VANCOUVER — A proposed class-action lawsuit against the Canadian government says Indigenous people removed from their communities and placed in group homes beginning in the 1950s suffered physical, sexual and psychological abuse that "was commonplace, condoned and, arguably, encouraged."

The Federal Court lawsuit filed this month in Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»says Indigenous children across the country were forcibly removed from their homes and taken "to live with strangers — sometimes hundreds of kilometres from their families and Indigenous communities."

Lawyer Doug Lennox said the lawsuit seeks compensation for those harmed by the country's historic policy of assimilation.

"There have been a variety of forms in which this policy has been implemented," he said. "Most notably with residential schools, but in other areas as well, such as day schools, such as the 60s scoop, such as boarding homes."

From the 1950s until the 1990s, the Canadian government forced many Indigenous, Inuit and Métis children into group homes, and those taken from their families under the program haven't been covered by legal settlements involving residential schools, day schools and boarding homes, Lennox said.

"We got calls from Indigenous people asking, 'well, where do I fit in? My experience was similar, but I wasn't in a day school, I wasn't in a boarding home. I was in a group home," he said. "This is a group that has unfortunately been missed up to now, but I think that mistake can be corrected reasonably and fairly and hopefully soon."

Canada's group home program ran into the 1990s, and involved taking Indigenous, Inuit and Métis children from their families and placing them into dorms, hostels and group homes, "distinct" from foster homes and residential schools.

The class-action says the program was part of Canada's "policy of forcibly assimilating Indigenous peoples," leading to the systematic eradication of "the culture, society, language, customs, traditions, practices and spirituality of the plaintiffs and other class members."

Some of the homes were operated by church groups and others staffed by the Canadian government, and they didn't support Indigenous languages and cultural practices, causing those who lived in the homes to experience "profound disruption and disconnection" from their families and communities.

The lawsuit asks for unspecified damages against the Canadian government for breach of fiduciary duties and negligence, but there has been no response filed to the lawsuit and the allegations remain unproven and untested in court.

A statement from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada said that "Canada has taken significant steps to resolve claims concerning historic harms committed against Indigenous children outside of the courts, whenever possible."

"Canada recently received the claim and is in the process of reviewing it to determine next steps," the statement said.

The case has four lead plaintiffs, including Carol Smythe, a member of the Nisga’a First Nation in British Columbia, who claims she was placed in a group home in 1977 when she was 13 in Aiyansh, B.C.

She alleges she was verbally and physically abused at the home, and witnessed other children being physically and sexually abused.

"The entire experience was terrifying for her," the lawsuit says.

Another B.C.-based plaintiff, Reginald Mueller, a member of the Tsqéscen First Nation, claims he was taken from his community when he was 10 in 1969 to stay in hostels that "did not support Indigenous language and culture."

Plaintiff Donna Kennedy, a member of the Garden Hill First Nation in Manitoba, alleges she was 13 when she was removed from her home in 1966 and taken to a dormitory operated by the United Church of Canada for four years.

Plaintiff Toby Forest, of the Lac La Ronge First Nation in Saskatchewan, claims the Canadian government removed him from his community in 1968 when he was seven, and took him to the Timber Bay Children’s Home.

The home had a dormitory run by a religious group that was contracted by the Canadian government as part of the group home program, where Forest alleges he was physically abused.

"He tried to escape from the home, and to return to his family 11 times," the lawsuit says. "On his 11th attempt, he made it back to his parents in Sucker River, Saskatchewan. He did not go back to Timber Bay Children’s Home after that."

"Canada had detailed knowledge of the breach of Aboriginal and treaty rights and the widespread psychological, emotional, sexual and cultural abuses of the plaintiffs and other class members," the lawsuit says. "Despite this knowledge, Canada did nothing to remedy the situation and continued to administer the group home program, thus continuing to permit the perpetration of grievous harm to the plaintiffs and other class members."

Lennox said the lawsuit involves Indigenous people who "slipped through the cracks" of other compensation claims involving residential schools, day schools and boarding houses,

"This case is about recognizing this other program that has so far been uncompensated, the group homes program, recognizing that it was a similar and further form of harm on indigenous peoples," he said. "And trying to rectify that harm, trying to right this sad chapter of our history and to further goals of reconciliation in our country."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 14, 2024.

Darryl Greer, The Canadian Press