Vancouver’s tree canopy cover increased to 25 per cent in 2022 from 21 per cent in 2013, according to a consultant’s study commissioned by the city.

The Diamond Head Consulting report — published in June and recently posted to the — found the four per cent increase was distributed among both public and private land.

Street boulevards, parks and private land showed the highest increases in canopy, while laneways and city-owned properties saw a more modest increase in canopy cover, the report said.

At the same time, the report included a map of �鶹��ýӳ��that showed some city blocks saw a net loss in tree canopy between 2018 and 2022.

Those areas included sections along the Cambie Street corridor, where the Oakridge redevelopment continues and neighbourhoods where housing developments have either been built or are under construction.

Downtown and pockets of the east side also saw some tree loss, with tree removals on private land comprising most of the canopy loss.

'Canopy loss is usually permanent'

Under the city’s protection of trees bylaw, replacement trees must be planted for trees removed, but it is often not possible to replace the canopy area lost on a development site, the report said.

“In these cases, the canopy loss is usually permanent unless it is compensated for with new trees on public land or on other private properties,” the report said.

The study was done prior to the mass ongoing removal of trees in Stanley Park related to the hemlock looper moth infestation. Park board staff has estimated 160,000 trees have to be cut down. That project was announced in November 2023.

“The 2022 canopy analysis detected a significant amount of dead/dying trees in Stanley Park,” the report said.

“The major hotspots of tree mortality are in the northern portion of the park and just south of third beach on the west side of the park. These observations are only representative of the year 2022 and are subject to change.”

East-west canopy cover gap remains

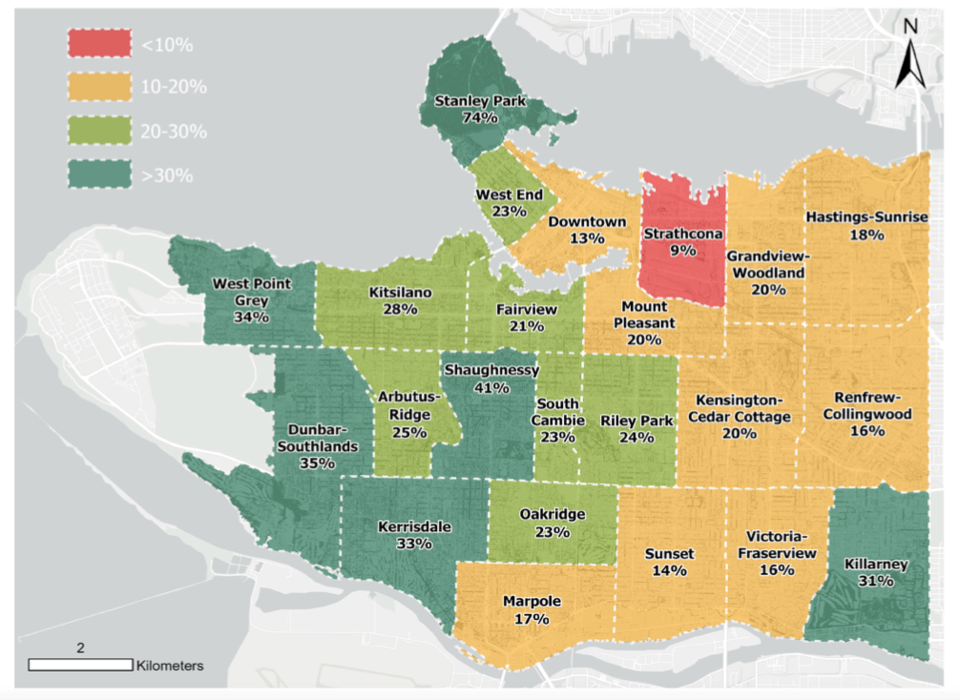

The report showed that Vancouver’s canopy cover has not been evenly distributed across neighbourhoods. The consultant found canopy cover was highest in neighbourhoods with larger properties containing more soil volume and space for trees.

Those neighbourhoods were Shaughnessy, Dunbar-Southlands, West Point Grey and Killarney, which all had canopy coverages of more than 30 per cent. Strathcona, Sunset and downtown had the lowest canopy cover.

Strathcona was the only neighbourhood with tree canopy cover of less than 10 per cent, with the report explaining the area contains “impervious light industrial uses,” including food terminals and a rail corridor.

Sunset's tree canopy was at 14 per cent, while downtown was found to be at 13 per cent.

�鶹��ýӳ��tree canopy increase comes amid regional decline

Canopy cover describes the area shaded by a tree's branches, stems and leaves when viewed from above. The consultant assessed Vancouver’s tree canopy by using aerial imagery and light detection and ranging technology.

The growth in Vancouver's tree canopy comes after a recent Metro �鶹��ýӳ�� that found the region's overall canopy had declined one per cent between 2014 and 2020. In some rapidly developing communities such as Coquitlam, tree canopy loss climbed to four per cent, while Vancouver, Maple Ridge and the City of Langley saw slight increases.

The City of �鶹��ýӳ��has adopted a 30 per cent canopy cover target by the year 2050. For comparison, Seattle has a 30 per cent target by 2037 and Portland wants to be a 33.3 per cent by 2035. Toronto's target is 40 per cent by 2050.

Last month, �鶹��ýӳ��council unanimously approved a motion from OneCity Coun. Christine Boyle and Green Party Coun. Adriane Carr that called for a plan to plant 100,000 new trees that can withstand the changing climate.

The timeline on when that goal could be reached is now in the hands of city staff, but Carr said Monday that she wants to see a focus on Strathcona and the Downtown Eastside, which continue to see a deficit of trees.

'A matter of money'

In the summer of 2021, 117 people died in the city of, according to a �鶹��ýӳ��Coastal Health “heat dome” report referred to by Carr A factor in those deaths was “the absence of tree canopy and other green space to provide protective cooling,” the report said.

“I'm not going to give this as an excuse, but just as a reality check — where you have a lot of pavement and you don't have as many side boulevards to sidewalks, it costs a lot more to plant a tree,” she said.

“So, it's a matter of money. You've got to invest in the tree canopy, both in the planting of trees, but also in the care and maintenance of the trees.”

In addition, Carr wants to see the city return to a program that offered small trees for sale to residents at an affordable price — she believes it was $10 at the time — to encourage more people to build more canopy in neighbourhoods.

An “adopt-a-tree” program is another idea, she said, noting the present drought conditions.

The urgency in growing the city’s tree canopy come as Vancouver’s government and its provincial counterpart move to open up single-family neighbourhoods to townhouses, six-storey residential buildings and other forms of multi-family housing.

“So you can imagine, as the ball gets rolling on that kind of development, there are many lots that have trees on the private portion of those lots — a lot of trees,” Carr said. “So that's one big worry.”

Vancouver's tallest tree is 66 metres

Some of the consultant’s other findings state:

• Approximately 35 per cent of the city’s public land was covered by trees compared to only 17 per cent of private land uses. Private land had almost twice the land area of public land, but roughly half the canopy cover.

• Parks had the highest canopy cover, followed by roads, city-owned properties, private land schools and then laneways. Increases in park canopy cover was attributed to tree regeneration through restoration efforts in locations such as Everett Crowley Park in Killarney.

• Of the 2,887 hectares of canopy area in Vancouver, 1,805 hectares or 63 per cent was on public land and 1,082 on private land.

• Stanley Park is home to the tallest trees in Vancouver, with 100 trees taller than 60 metres. The tallest is 66 metres.

• Carbon storage and annual sequestration increased by 23 per cent between 2018 and 2022.

An additional 116 hectares of tree canopy is needed to achieve a one per cent increase in Vancouver's canopy cover. That would require planting 23,000 trees, according to calculations in the report.

On a larger scale, the report concluded that boosting the city-wide canopy to 30 per cent from its current 25 per cent would require planting 175,000 new trees, including 50,000 to make up for losses due to age, weather, pathogens and pests.

X/@Howellings