The Overdose Prevention Society has found a new location for a drug consumption facility after learning it had to vacate its current site set up in a parking lot on West Pender Street by the end of the month.

Sarah Blyth, executive director of the society, said the new site will open in April in a private building at 151 East Hastings St., which is adjacent to the Insite supervised drug injection site.

“I just kind of raced around and found a place,” she said Thursday. “I’m happy because it will be more of a permanent location for now. We’ll be able to accommodate the people we accommodate now on West Pender.”

Blyth said the back of the property has a large outdoor space for people who choose to smoke drugs — a method of drug use that has grown in popularity in recent years and has been the leading mode of consumption linked to overdose deaths.

The society sees several hundred drug users per day visit the site at 99 West Pender St., which is a large open-air space with tents, picnic tables, washrooms and surrounded by a tall fence.

The property belongs to Kenstone Properties, which said in an email that the short-term lease with the society is coming to its natural end date at the end of the month.

“OPS has been circulating a narrative that we are forcing them out of the site — this is not the case,” said Ming Leei-Lim, property manager at Kenstone, noting she advised the society months ago that the lease would not be renewed.

“This was always meant to be a temporary arrangement during the pandemic. We need to proceed with environmental drilling and testing as part of our listing of the site.”

How long the society will operate at its new site on East Hastings Street is unclear, with the city announcing in February that the Balmoral Hotel will be demolished this year. The notorious single-room-occupancy hotel is adjacent to the society’s new location.

The city purchased the Balmoral in 2020 from the Sahota family. The sale occurred three years after the city forced the Sahotas to close the hotel because it was in poor condition.

In February, the city said that after receiving two third-party engineering reports on the current fire and structural risks at the hotel, it became clear the building has deteriorated to the point that it poses a danger to the public and adjacent buildings.

The city’s decision to demolish the Balmoral was confirmation of what BC Housing CEO Shayne Ramsay told Glacier Media in May 2021 — that the Balmoral would be demolished and possibly part of a land assembly purchase to develop a large housing and health centre on the block.

Such a real estate move would mean buying at least two properties from Concord Pacific, another property belonging to the Sahota family, a building that houses the Insite injection site, a cannabis dispensary — located in same low-rise building as the society’s new location — and a few other properties.

Land trust

Developer Peter Wall of Wall Financial has proposed the city and province work with him to build at least 168 units of housing, a medical centre, injection site and treatment rooms on the properties.

In the meantime, Blyth said she had a meeting scheduled this week with the Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Community Land Trust Foundation to explore ways of securing a permanent site to avoid having to move again.

Drug consumption sites have increased in Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and across the province since Insite opened in September 2003 — one of the first legal sites in North America, along with a small facility at the Dr. Peter Centre in the West End.

As of December 2021, there were 39 overdose prevention and supervised consumption services in B.C., including 13 sites offering inhalation space, according to the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions.

But there are no large, indoor stand-alone inhalation sites in the province.

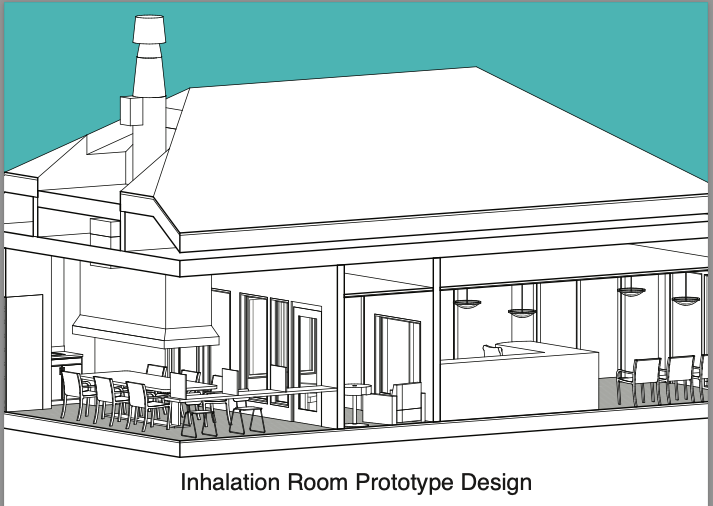

In 2019, Russell Maynard, a board member of the Overdose Prevention Society, secured a $30,000 grant via the provincial government to develop a prototype for a stand-alone inhalation room.

The study team for the research paper included Dr. Marcus Lem, the former senior medical advisor for opioid addiction and overdose prevention policy at the BC Centre for Disease Control.

Architect Sean McEwen, who designed Insite and Onsite, and Hannah Leyland, an intern architect in Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»whose graduating architecture thesis examined the design of drug consumption spaces, also worked with Maynard.

The team settled on a modular design similar to the modular housing that currently exists across Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»for people at risk of homelessness. Imagine a double-wide mobile home, with a pitched roof, a porch and enough space for six people in a room to smoke drugs.

Important to the design was a ventilation and filter system, with the space for smoking to be airtight and separate from staff and supervision areas. WorksafeBC would also be consulted about final design and workplace protocols for staff.

In the end, a prototype was never built.

“I wrote that report three or four years ago, and still nothing,” said Maynard, a former manager at the Insite injection site, in a recent interview.

'Cost is a factor'

The Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions referred questions about the report to the BC Centre for Disease Control, which said in an email that “the work did not continue once the project was complete.”

The centre noted that “feedback from stakeholders indicates that cost is a factor in designing indoor inhalation overdose prevention services.” The estimated cost to design and build a prototype was $850,000. Annual operating costs were estimated at $321,000.

“BCCDC continues to work with stakeholders on making safe inhalation sites accessible,” the email said.

“This includes providing recommendations for outdoor inhalation overdose prevention services of the BC overdose prevention services guide, as well as ongoing work to develop guidelines including ventilation standards for indoor sites.”

Dr. Mark Lysyshyn, deputy chief medical health officer for Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Coastal Health, also pointed to the costs of developing indoor inhalation sites.

In particular, he said, would be the expense to create occupational health and safety requirements that would be safe enough for workers "to rescue people having overdoses if there are other people smoking in the environment.”

“Ideally, we would like people to have indoor spaces, as well,” Lysyshyn said. “But unfortunately that would take away our budget for all of the other indoor supervised consumption spaces that we have. And so we have to sort of balance that.”

He said there are currently five sites in the Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Coastal Health region that provide supervised inhalation services, two of which are in Vancouver, including the site at 99 West Pender St. All are outdoor spaces.

'Model that is working'

Indoor sites mentioned in Maynard’s report included locations in Lethbridge, Alta. (capacity of three smokers), Copenhagen (12 smokers) and Paris (four smokers). Lysyshyn said he knows of a site in Victoria that offers an indoor inhalation space for one smoker at a time.

“If a person has an overdose, then the responder has to don personal protective equipment and go in,” he said. “I guess for a small site that's not very busy, you can serve some people like that.”

But such a model, he said, wouldn’t work in the context of the Downtown Eastside, where there are hundreds — perhaps thousands — of smokers. Lysyshyn believes the open-air site at West Pender is one of the busiest in the world.

“That is a model that is working,” he said, noting the high number of overdoses reversed regularly at the site. “Although it's nice for an individual to be able to smoke inside — and we agree with that — it's just that we need models that work. And so that's why we're continuing with this model.”

At the very least, Maynard said, the BC Centre for Disease Control and the health authority could park a construction trailer on the back of the property of the Overdose Prevention Society’s new site, add a proper ventilation system and test it for smokers.

While he agreed the number of drug users in Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»is substantial — and responding to their present needs is crucial to save lives. But having outdoor inhalation facilities continuing to operate in the city and in other parts of the province, where the weather is harsh during the winter months, is not a long-term solution.

“When you've been doing these outdoor sites for at least four years, at what point is it no longer an emergency?” Maynard said.

“That's all I'm saying — is there needs to be a transition from the emergency into a public health model. People sitting underneath a tent with water running under their feet in the rain, in low light and in the winter is not a public health setting by any definition.”

'Huge expense'

Blyth, meanwhile, is of two minds on the present and future of inhalation sites — agreeing with Maynard that permanent indoor facilities are required, while at the same time emphasizing the need to have emergency pop-up spaces in place now to respond to the overdose death crisis.

The cost to build and operate a facility may seem prohibitive, but not when compared to the health care costs associated to drug use, said Blyth, noting the number of people who end up with brain damage and other injuries.

“That’s a huge expense,” she said. “So if you think about in terms like that, you’re saving money.”

More than 2,200 people died of a drug overdose in B.C. last year.

Data released by the BC Coroners Service last month showed the highest percentage of overdose deaths in the province from 2017 to 2020 was the result of smoking rather than injecting drugs.

@Howellings