Due to the digital revolution, death and data are becoming intertwined.

With more and more of our lives recorded and stored in different ways, a group of University of British Columbia (UBC) researchers wanted to look at how what should happen to it. Janet Chen, , grew up during the digital revolution and wondered about how social media will deal with her data post-death.

"It struck me that many of the platforms I use don’t have great tools to support that data after I’m gone,” she says in a press release. “We wanted to look at how to curate this data both while living, and after death.”

Chen and her fellow researchers felt Facebook and Google options currently available fell short.

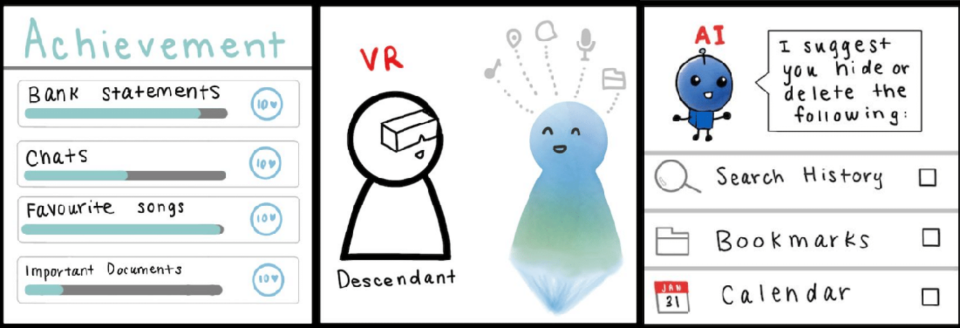

The study offered participants 12 different options and had participants go through a workbook and react to the different ideas. The options varied in what they offered and how they worked, ranging from an AI that people in the future could interact with, based on a person's data to a preparedness badge that one would get once they set up their data to setting up a way to share stories or photos far into the future (at least 50 years).

Another, called the 'Box of Data' posed the idea of data becoming physical. So someone's favourite songs would become a vinyl record, their favourite places according to Google Maps would become postcards, and popular social media posts could be made physical in other ways.

"The researchers also explored different levels of user-control by presenting human-selected, computer-selected and AI-powered alternatives," states UBC in the release. "These employed techniques such as nudging the user to complete tasks, collaborating with family and friends and gamifying the process.

The least popular option was the AI, only a quarter liked that idea. The most popular was the 'Made for You' idea, where a smart assistant would create video montages of photos and videos. People could choose during life if photos or videos should be added to that.

"One concept people clearly did not like at all was an AI-powered replica of the deceased person, which would interact with future generations. They said it was scary and creepy," says Chen in the release.

Some of the different data ideas. By UBC

Some of the different data ideas. By UBCChen and her fellow researchers don't think it'll be long until this issue is commonplace.

“Ten years from now it will likely be quite commonplace for people to be thinking about the reams of data they have online, and there is a huge opportunity for research with larger populations and new interfaces to support people who care about what happens to their data,” said Dr. Joanna McGrenere, who co-authored the study.

In the conclusion of the study the authors write about how people will need to balance wanting to leave something meaningful with what should be shared, deleted and saved.

"Maintaining control over after-death self-representation was also important for maintaining a sense of agency, as highlighted by participants’ reactions to AI replicas and collaborative games," they write. "These results and the design directions we present can help anticipate evolving user needs for how to prepare an ever-increasing amount of data distributed across a myriad of services and platforms."