The data is contained in an audit report that says reasons for the decrease are likely related to new province-wide policing standards implemented in January 2020 in combination with the simultaneous adoption of a VPD policy on street checks.

“It is a fair argument to make that to whatever extent discrimination played a part in previous street check practices, the arrival of the [provincial] standard and VPD policy has had the practical effect of virtually eliminating street checks in Vancouver,” said , which goes before the В鶹ҙ«ГҪУі»ӯPolice Board Thursday.

The report’s authors acknowledged “public dialogue” also played a part in the decrease in street checks, which police say they use to make enquiries into “reasonable and legitimate” public safety concerns such as suspicious activity, crime prevention or intelligence gathering.

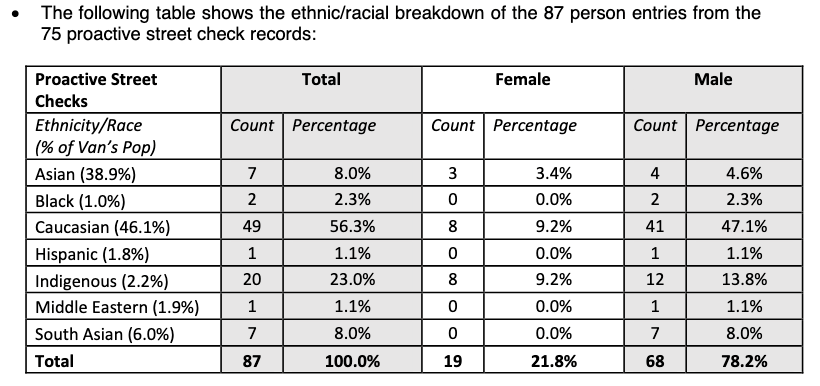

Data for the period Jan. 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 shows police conducted 75 “proactive street checks” involving 87 people across all four policing districts, including 20 on Indigenous people and two on Black people.

Eleven of the checks on Indigenous people stemmed from an officer’s concern about a person’s well-being or safety, said the report, which provided an example of an officer who questioned a violent sex offender from the Fraser Valley, who was accompanied in his car by a female passenger.

The passenger requested to leave after police made the stop.

“The driver was released and he left,” the report said. “Police then spoke with the passenger who stated she had not been harmed by the driver, but also stated he was ‘really weird.’"

Other people police checked last year included 49 Caucasians, seven South Asians, seven Asians, one Middle Eastern and one Hispanic. Of the 87 people, 68 were men and 19 female.

Police said the majority of checks were conducted for a public safety reason.

“Eighty-seven percent of the people in the 75 proactive street checks were a suspect in an average of 19.5 different criminal investigations prior to the street check,” the report said.

“The remaining seven street checks did not have an articulated public safety purpose. This is not to suggest that the officer did not have a public safety purpose at the time, rather they did not provide it in the record.”

Image courtesy VPD

Image courtesy VPDThe report noted the decrease in street checks from 2020 to 2019 was 94 per cent.

However, that percentage is based on an additional number of “street check records” filed by police in 2020, which were later determined not to fit the definition of a street check.

Police actually produced 261 “street check records” in 2020, involving 353 people.

The audit found 186 of those “records” were “misclassified as a street check, while the remaining 75 records were an actual proactive street check” — an oversight police say is typical of sweeping changes to any practice.

Police generated 4,544 “street check records” in 2019, but the report doesn’t say whether all or how many constituted a “proactive street check,” as defined under new provincial and VPD policies.

The report also doesn’t break down the 2019 data for racialized groups.

A in November 2020 said data obtained under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act showed the proportion of checks in В鶹ҙ«ГҪУі»ӯtargeting Black people rose in 2019 to more than five times their share of the population.

Checks on Indigenous people hovered around six times, according to the report by reporter Jon Woodward.

The VPD’s own data posted on its website in 2018 showed that Indigenous and Black people were overrepresented in street checks between 2008 and 2017, when police conducted 97,281 checks.

Of those checks, 15 per cent (14,536) were of Indigenous people and more than four per cent (4,365) of Black people. Indigenous people make up just over two per cent of the population in Vancouver, and Black people less than one per cent.

That data prompted the B.C. Civil Liberties Association and the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs to lodge complaints with the Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner and demand the practice be abolished.

The organizations said the data created “a strong suggestion” that street checks were being conducted in a discriminatory matter, which Police Chief Adam Palmer flatly denied.

The audit report said an important question to consider is whether groups overrepresented in the data are because police acted discriminatorily, or are there other factors in play.

“Indigenous peoples are consistently overrepresented in homeless counts, they are 10 times more likely to use a homeless shelter, and are even more likely to be living on the street, unsheltered, or ‘absolutely homeless,” the report said.

“It would be unrealistic to expect that police contacts at an aggregate level would remain unaffected by all these troubling societal issues and risk factors.”

The audit comes after more than two years of debate in the community, at city council and at the police board over street checks. The VPD has conducted its own review of the data and an independent report was commissioned into the practice.

Both reports concluded there was no bias towards any one racialized group.

Mayor Kennedy Stewart, who doubles as chairperson of the police board, and city councillors, have also called on the practice to be abolished, saying it is not necessary and further targets racialized and vulnerable people.

Representatives from the B.C. Civil Liberties Association and Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs could not be reached to comment on the audit report before this story was posted.

@Howellings