It’s an anniversary city officials will not be celebrating next week.

For the 10th consecutive year, hundreds of volunteers will take to the streets and shelters March 12 and 13 to count the number of people who do not have a home in Vancouver.

Mitchell Lagimodiere and Kelli Lubbers are tenants at the Sarah Ross House modular housing building on Kaslo Street. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

Mitchell Lagimodiere and Kelli Lubbers are tenants at the Sarah Ross House modular housing building on Kaslo Street. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

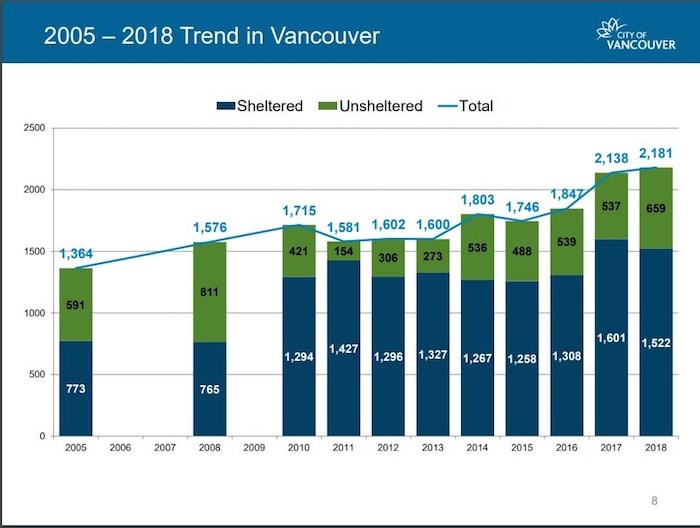

Last year, were recorded as homeless — 1,522 in some form of shelter and 659 on the street. It was an all-time high for Vancouver, with previous Metro Vancouver-led counts showing the city’s homeless population was once at 1,364 in 2005.

So what will the population be this year?

If the number of temporary modular housing units opened across the city since last year’s homeless count is used to answer the question, then the easy math would suggest �鶹��ýӳ��will see a decrease in its homeless population.

Only the 78-unit complex in Marpole was open during last year’s count. Since then, nine more modular housing buildings opened across the city, including in Fairview Slopes, Renfrew-Collingwood and the Downtown Eastside.

The most recent one — Nora Hendrix Place at Union and Gore streets — opened Sunday.

Some units in the buildings still have to be tenanted, but about 500 people are now living at the 10 sites. When all of the units are occupied, that will mean 606 people will be housed.

Not every tenant — who range in age from 20 to 89 — came directly from the street, but the city contends 80 per cent were either in a shelter or living outside before moving into a suite. So that accounts for about 400 of the 500 tenants.

The 52-unit modular housing building on Kaslo Street is known as Sarah Ross House. It opened last summer. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

The 52-unit modular housing building on Kaslo Street is known as Sarah Ross House. It opened last summer. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

The remaining 20 per cent were at risk of becoming homeless or living in precarious housing situations, according to Abi Bond, the city’s managing director of homelessness services and affordable housing programs.

The breakdown suggests fewer people will be on the street and in shelters this time around.

But that’s the easy math.

What complicates an answer to the equation of whether Vancouver’s homeless population has decreased since last year are two sobering data points.

The first one is that 78 per cent of people surveyed in the March 2018 count said they last paid rent in �鶹��ýӳ��prior to becoming homeless, dispelling a long-held myth that the city's population is being fueled by migration from other cities and provinces.

The second point is that 52 per cent of people surveyed said they had been homeless for one year or less.

That has been a reoccurring trend.

The reasons vary, but the drivers of homelessness, as identified in city reports, have included expensive rents, low vacancies, job loss, people living with mental health and addiction issues and lack of housing for people leaving hospitals, jails and foster care.

Those are factors Mayor Kennedy Stewart is keenly aware of, and it is why he could not provide a prediction on what this year’s count will reveal, although he pointed to the opening of the modular housing buildings in his response to the question.

“All our hopes are really pinned on the temporary modular housing,” said Stewart, who plans to participate in next week’s count. “I’m hoping that makes a difference.”

‘Stepping stones’

Mitchell Lagimodiere on the path that he and friends made outside Sarah Ross House. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

Mitchell Lagimodiere on the path that he and friends made outside Sarah Ross House. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

It has made a difference for Mitchell Lagimodiere, who lives in a suite at a modular housing building on Kaslo Street near the 29th Avenue SkyTrain station. It’s called Sarah Ross House. The 56-year-old self-described jack of all trades was not counted in last year’s count.

Why?

“I was hiding,” he said. “They couldn’t find me.”

Lagimodiere may be familiar to as the guy who built a bunker into the side of a hill in a ravine near Lakewood Street and 12th Avenue. He lived in the fortified space, complete with a bed, lighting and venting for about seven months. He even rigged up a DVD player.

His large collection of tools took up much of the space.

A combination of a police incident involving a friend and media attention ended his days in the bunker. He found a spot in a shelter at East First and Commercial Drive, which connected him with people who arranged for a suite at the Sarah Ross House.

Lagimodiere was grateful for the room. It was a bonus, he said, that it wasn’t in the Downtown Eastside. He moved in last August.

“I had a bad drug habit when I was younger, and to go downtown would be just asking to get back into it,” he said, sitting at a table in the building’s common room while an episode of The Simpsons played on the television. “There’s no way I’ll go back down there.”

His room has a bed, small kitchen and washroom. He’s filled it with his tools. He’s got a lock on his door, which, he said, gives him peace of mind. He also has access to laundry and a computer room. If he doesn’t cook himself, he can get a meal prepared in the building’s community kitchen.

Atira Women’s Resource Society, the non-profit that manages the 52-suite building, ensures tenants have access to support services such as health care, counselling and help with income assistance. Harm reduction supplies are available near the front door.

Movie nights, bingo nights and a women’s sharing circle are some of the programs available. Tenants can volunteer in the kitchen and management is currently developing a life skills program.

The cost for Lagimodiere to live there is $375 per month, a sum that is paid for with the income assistance he receives from the provincial government.

For all he has, his new surroundings took some getting used to.

“I just couldn’t come inside,” said Lagimodiere, who is originally from Winnipeg but moved west to �鶹��ýӳ��as a young boy with his mother to escape being recruited into gangs. “It took a while to adjust. I actually didn’t sleep here for the first month. I found it real uneasy. I’d spend the day here and then turn around and go sleep outside.”

Having a place to live has allowed him to reconnect with some of his 12 children. He believes one of his sons from Prince George will be in town to celebrate his birthday later this month.

In the past few months, he said, he’s also been thinking about returning to �鶹��ýӳ��Community College to improve his limited literacy skills; up until three years ago, Lagimodiere said, he couldn’t read or write.

Kelli Lubbers and her dog, Bubba, in her room at Sarah Ross House. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

Kelli Lubbers and her dog, Bubba, in her room at Sarah Ross House. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

For now, he spends his days doing odd jobs around Sarah Ross House. He recently built some gravel walkways with fellow tenants and friends. He’s also built shelves for tenants, including Kelli Lubbers, who was in hospital during last year’s homeless count.

Lubbers, 40, had been living in a single-room-occupancy hotel in the Downtown Eastside until she contracted an infection, which she blamed on the condition of the hotel. She learned about Sarah Ross House through the building’s manager.

“This definitely helps with my stepping stones,” said Lubbers, who noted she was once certified as a “Red Seal” chef. “My next goal is to get clean [from using drugs]. I don’t use very much, I use actually very little but I can’t get rid of it. And I really need to. I don’t know how I’m going to go about doing that, yet.”

Since Lubbers moved in, she got a pit bull puppy she named Bubba, which played at her feet for a portion of her interview with the Courier.

“I’m much more stable, way more relaxed,” she said of her life at Sarah Ross House.

Lagimodiere feels the same.

“I love it — it’s great,” he said. “I feel at home here now. I got friends out there right now who would kill to get in here.”

$66 million for 606 modular units

This City of �鶹��ýӳ��graph shows the steady increase in homelessness.

This City of �鶹��ýӳ��graph shows the steady increase in homelessness.

The mayor wants to get more people into housing, but he’s not promising what his predecessor, Gregor Robertson, did — to set a deadline to put an end to the number of people living on the street.

“I was a boy scout for a long time and the motto is ‘I’ll promise to do my best,’ and that’s exactly what I’m doing,” said Stewart, noting he’s met with politicians in Victoria and Ottawa to press for more funding for modular and permanent housing in Vancouver.

As Robertson acknowledged in to end “street homelessness” in 2015, any reductions to homelessness have to be done with millions of dollars of commitment from the provincial and federal governments.

Robertson, who served 10 years as mayor, believed the governments of Christy Clark in Victoria and Stephen Harper in Ottawa would address the homelessness crisis and help him meet his goal. That didn’t happen, he said, and the homeless population increased from 1,576 in 2008 to 2,181 last year.

During the provincial Liberals’ time in government, they funded 13 supportive housing buildings, bought and renovated more than 20 Downtown Eastside hotels and provided funding to operate shelters and offered rent supplements for low-income people.

Still, the homeless population increased in �鶹��ýӳ��and throughout the region.

Then-housing minister Rich Coleman would repeatedly tell reporters the Liberal government had invested more in housing than any jurisdiction in Canada. The provincial Liberals and Harper’s Conservatives lost both elections as Robertson was winding down his last term.

In leaving office last fall, Robertson argued the newly elected NDP-led provincial government and the Liberal-led federal government were more aligned with the city and region’s push to build housing for homeless people.

He pointed to the $66 million for the 606 modular units in �鶹��ýӳ��and the federal government’s $40-billion, 10-year national housing strategy announced in 2017 to reduce chronic homelessness by 50 per cent in Canada.

That is an alignment Stewart — a former NDP MP — has also referred to when discussing homelessness, noting the provincial government’s recent budget forecast called for another 200 modular housing units province-wide this year.

“The province is the reason we have the first 600 units of [modular] housing, but I’m glad that they’ve made more available and I’m going to take as many as they’ll give me,” the mayor said.

But while Stewart and Abi Bond of the city’s homelessness services department say funding for modular housing is crucial, it’s the drivers of homelessness that they say need to simultaneously be addressed by the provincial and federal governments.

“As long as we still find people entering homelessness in that way, we’re going to see the homeless numbers affected,” said Bond, referring to people living with mental health and addictions and other factors related to poverty that leave people on the street. “We need big system changes in order to prevent that from happening. And we need more investment in supportive housing, not just in �鶹��ýӳ��but across the region, as well.”

Added Bond: “If new people are becoming homeless every day, every year, then we need a system that’s going to pick them up quickly and re-house them as fast as possible. But right now, our shelters are full to kind of bursting and we don’t have sufficient supportive housing options for people in the year that they’ve become homeless. So unless we can start to do that, I think we will see continued pressure on our system.”

All types of housing for all types of people

Housing Minister Selina Robinson, Mayor Kennedy Stewart and Abi Bond, the city’s managing director of homelessness services. Photos by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

Housing Minister Selina Robinson, Mayor Kennedy Stewart and Abi Bond, the city’s managing director of homelessness services. Photos by Dan Toulgoet/�鶹��ýӳ��Courier

Housing Minister Selina Robinson and Social Development Minister Shane Simpson are troubled by Vancouver’s homeless crisis, as they are about people living on the street and in shelters in the rest of the province.

In separate interviews last week, both ministers rattled off a list of initiatives the NDP-led provincial government has taken since elected in 2017 to address homelessness.

Some of that list included modular housing, investments in mental health and addictions services, increases to income assistance, the move to set up a rent bank, keeping the allowable rent increase at 2.5 per cent and making post-secondary free for young people leaving foster care.

The government, however, did not open any new stand-alone permanent housing for homeless people in �鶹��ýӳ��since last year’s homeless count. Only 52 units of the 198-unit Olivia Skye building at 41 East Hastings — which opened in March 2018 — rent to single women at the provincial welfare rate of $375 per month.

In addition, the government paid $12.5 million for the Jubilee Rooms near Main and Hastings, which opened in June 2018. But that purchase was done to accommodate nearly 80 tenants evicted from the Regent Hotel, which the city closed because of its dilapidated state.

Both ministers would not predict whether Vancouver’s homeless population would decrease this year but said they were hopeful progress had been made since last year’s count.

Robinson, who was in �鶹��ýӳ��March 3 to open the 52-unit Nora Hendrix Place at Union and Gore streets, said her ministry continues to work with municipalities to bring housing to their communities, noting homelessness is a B.C.-wide problem.

She provided some examples of progress — one in the Whalley area of Surrey, where people were moved off a notorious strip and into modular housing, and another in Smithers, which she said will close its shelter because of the construction of modular housing in the northern community.

“As a town, they are very excited that they don’t need their shelter anymore,” Robinson said.

'30-point' housing plan

But, she said, the government is not solely focused on modular housing to reduce homelessness. She pointed to the government’s 30-point housing plan, saying addressing homelessness has to include providing all types of housing for all types of people.

“We recognize it’s not any one thing,” Robinson said. “We need affordable rental, we need seniors housing, we need housing for families, we need to address what’s going on for renters — the fixed-term lease loophole. Fixing all of those pieces is about preventing homelessness.”

The drivers of homelessness that Bond referred to are expected to be a focus of the provincial government’s poverty reduction strategy, which Simpson said he will reveal in a couple of weeks.

“We know much of [being homeless] is linked to poverty — the connections, obviously, are very strong,” he said, noting the plan involves input and action from a range of government ministries. “If the issue of poverty reduction rests with my ministry alone, it’s not going to succeed. It has to be bigger than that, or we’re not going to have a lot of success.”

In the meantime, Vancouver’s homeless count will go ahead next week for its 10th consecutive year. The data, so far, has shown no significant signs that an 11th or 12th count will not be necessary.

“Obviously, we hope we’re going to see some progress,” said Simpson, the MLA for Vancouver-Hastings. “That would be great. But there’s still going to be significant numbers of people out there who are struggling with homelessness. That’s a for sure.”