Kennedy Stewart has been out of the ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠mayor’s chair for almost a year now.

Thousands of voters miss him, thousands are glad he’s gone.

Stewart won the support of almost 50,000 people in the October 2022 election.

But the former NDP MP proved no match for ABC Vancouver’s Ken Sim, who convincingly bounced Stewart from city hall after he collected 85,732 votes.

Why did Stewart lose by such a large margin?

There have been many takes, including reasons outlined by Glacier Media in this election night piece. Not included in that analysis was that Stewart partly lost the race because of his successful push to decriminalize drugs.

“I definitely think it contributed to my loss,” he said in an interview last week.

In November 2020, the city council of the day unanimously approved Stewart’s motion to have the City of ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠request a federal exemption under the country’s drug laws to decriminalize personal possession of all illicit substances within the city’s boundaries.

That move eventually led the provincial government to push for a provincewide exemption, which ended with the federal government giving the B.C. government the green light to run a three-year experiment across the province, which .

Did the province steal Stewart’s thunder?

Does he really believe the ballot question in 2022 was decriminalization?

Those are questions Stewart answers in his new book, “Decrim: How we decriminalized drugs in British Columbia.” The official launch is Sept. 26 at an event in Chinatown.

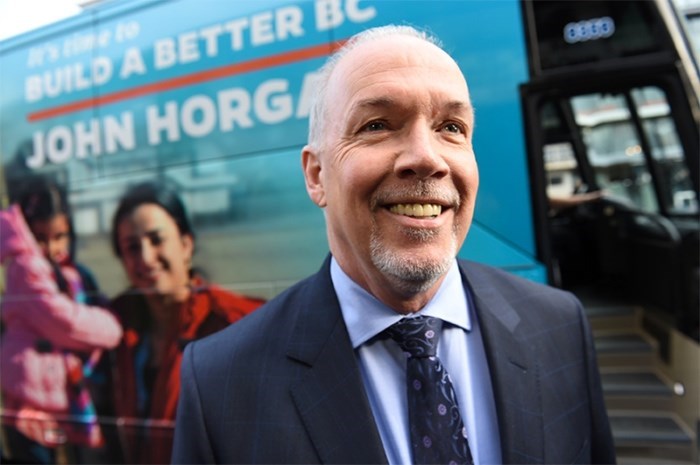

Glacier Media spoke to Stewart last week to learn about the fight for decriminalization and other insights into his time in the mayor’s chair, including his frosty relationship with former B.C. premier John Horgan and why Sadhu Johnston quit as city manager.

The following is a condensed and edited version of the interview.

When you ran for mayor in 2018, you did not campaign on decriminalization. Why?

I was quite practical and trying to work on things I thought I could accomplish. When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau says twice to your face that he's never going to decriminalize drugs, I didn't think it was something that I could accomplish. I thought it was something that was necessary. The drug user community had been advocating for this for a long time. But I didn't have it on my agenda because I didn't think there was any way I could do it.

What changed?

That all changed when Patty Hajdu became [federal] minister of health and proactively said to me, ‘Our lawyers have looked into this, and if you want to decriminalize drugs in ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠without the permission of the province, you can do it.’ So I said, ‘let's go.’

Earlier this month, the provincial government tightened up the three-year decriminalization experiment to ensure public spaces such as playgrounds cannot be areas where drug users can legally use drugs. What’s your take on the new rules?

Well, my first take was disappointment. Now that I've had a bit of a time away from politics, and more time to contemplate things as a professor, I think it's just a brand new thing that's starting to settle in. So it seems like more of an adjustment than a rejection. I’m kind of seeing it as positive because it's not municipalities and mayors and council saying we're against this in total. They’re just saying we want to protect our kids, which I think is a reasonable thing. In the end, it may mean that this has a better chance of surviving over the long term, if the community that opposes it has an opportunity to have their input, as well.

Throughout the book, you write that you believed the provincial government was never really interested in decriminalization, yet an application was sent to Ottawa and eventually approved. Did I read that correctly in the book that you believe Vancouver’s unanimous support in November 2020 for decriminalization forced the B.C. government’s hand?

I think that [then-B.C. premier] John Horgan was definitely against this. But what they underestimated was my very strong relationship with the federal health minister [Hajdu]. Of course, Horgan never spoke to me about anything. So how would he have any information about my relationship with the federal health minister? She had my back all the way through the whole process.

She was kind of saying you can go out on a limb if you want, but I'll be with you. Then we did it together. I think, in the end, the province was stunned when the federal ministry of health accepted Vancouver's application and was considering it. I don't think that they expected that at all. Then they had to quickly pivot and say, ‘Oh no, this is our idea.’

I didn’t realize you had such a contentious relationship with John Horgan when he was B.C. premier.

It was awful. I mean, especially through the pandemic. Everything was melting down — whether it was financially or unrest in the city. There was a very real threat of a convoy blockade in the downtown of Vancouver. And it's pretty disheartening when you can't get through to the premier to say, ‘We need help here.’ Luckily, the VPD [¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠Police Department] and local activists were able to make sure it didn't happen.

But we could have very easily had an Ottawa-style occupation here, as well. But from talking with big city mayors across Canada, their relationships with their premiers are often like this, but I don't think any of them were as bad [as my relationship with Horgan].

You write that he refused to reply to your team’s repeated meeting requests throughout your time as mayor.

At first, I was stunned by this because it took me weeks and weeks and weeks to schedule our first meeting. I went to Victoria and the meeting was like five minutes long, and he didn't want to talk to me about anything. And then there was maybe one or two [meetings] after that during the whole four years [I was mayor].

He just wasn't interested in Vancouver. It was just a big headache. That's what it seemed to me — a big headache, a big urban headache. And he was just way more interested in resource development and not so much in the core of the economy, which is, you know, cities.

And at one point, when you were still serving as an MP, he told you to “f@?! off.” What’s the story there?

It was all around the Trans Mountain pipeline. He wasn't the only other elected official to tell me to f@?! off. I was the basically the shadow minister for pipelines. I decided to go out against Trans Mountain and the federal NDP, the provincial NDP, the Alberta NDP — all of them were pro-Kinder Morgan. Things were getting pretty tense.

There was a call scheduled between me and John Horgan. He was the energy minister at the time and when I said I was opposed to this, he just told me to f@?! off and hung up the phone. That's probably where the bad blood started. It’s unfortunate he held a grudge or whatever it was because the city really could have used more help, especially through COVID.

When you were mayor, you mentioned a couple of times at news conferences that you had lost a family member to overdose in Vancouver. You never provided details on that person, but readers will now learn it was Susan Havelock, your brother-in-law’s sister. Why did you include her name and story in the book?

Post-election, I was able to sit down and talk with [Susan’s brother] and learn more about her history. I got specific permission from him to include her story in the book. I wrote the drafts and then showed it to him to make sure he was comfortable with what I wrote. Really, this is her story and it's trying to help people understand just how this is really different than anything else we faced before. It's not weakness, it's just a terrible thing that's happening to us socially that we need to come to grips with.

There have been various takes by many municipal politics’ watchers on why you lost the 2022 election to ABC Vancouver’s Ken Sim. Pushing for decriminalization was not among the takes I heard. But your press materials for the book says you believe it contributed to your loss. How so?

I definitely think it contributed to my loss because it just kind of reinforced this narrative that came from [Conservative Leader Pierre] Poilievre, and the Rebel News crews and [the documentary] ‘¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠is dying.’ That ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠is dying video got, I don't know, three million views. Just no way to counter it. My support for harm reduction was a big centre of that social media attack.

I’ve explained the structural reasons why I won and lost. I was pretty hard left and still am. That’s not the norm for ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠mayors. They're usually kind of much more centrist. Building a lot of rental housing, or at least getting it approved on the west side of the city certainly kicked that hornet's nest, too. The Broadway plan, subway expansion. So I think the west side of the city just had enough for me — and decriminalization didn't help that at all. (Editor's note: Sim told Glacier Media during the 2022 election campaign that he supported decriminalization.)

You mentioned former federal health minister Patty Hajdu earlier in our conversation. In the book you refer to her as “our Ottawa champion.” Explain.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made it explicit on many occasions — twice to me and in the media many times — that drug decriminalization wasn't on the table. And yet when Hajdu was appointed health minister, she knew that. But then she discovered that she had the autonomous ability to approve decriminalization — an exemption — and went for it.

She may say different because she's still in a fairly powerful cabinet position, but I think it contributed to [Trudeau] shifting her out of that position. I mean, she was a harm reduction practitioner in Thunder Bay, and very much believed in this and saw a window and joint minds met and away we went. So I'm really very grateful for her.

And now we get to see the impacts. The sky hasn't fallen. It hasn't stopped overdose deaths, but it hasn't caused the mayhem the right wing said it would.

You probably missed it, but ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠Deputy Police Chief Fiona Wilson said at a police board meeting this summer that “just to be clear, we don't think there's necessarily been a dramatic increase in public consumption” since decriminalization came into effect Jan. 31.

Oh, that's great.

But at the same time, people continue to die of overdose at a rate of about six per day in B.C. There are people who point to decriminalization and say the death toll is proof that the policy doesn’t save lives. So what do you say to those critics?

My observation is that it hasn't had any negative effects from what I can see. And it's probably had a few minor positive effects. So there has been drugs that have not been seized. Nobody ever thought that it would end [overdoses], but that it would just make things a little better. The kind of gruesome way I look at it is if 10 people are dying of toxic drugs, maybe with decriminalization only nine will die. So maybe it will have a slim impact.

But we have to get going on many other things [safe supply, treatment]. If we just continue the way we're going, or we roll things back, you're just going to have six people a day dying in British Columbia. The drug supply has changed forever. People still use drugs.

I found this national drug survey that said about 17 per cent of people had tried hard drugs in their lifetime. People go to a party on a weekend, they don't ever use drugs. Then one of their friends picks up cocaine and they have a little snort. It's laced with fentanyl, and they're dead. That's kind of where we're at. The policy prof in me says we’ve got to try different things, even though it's scary.

You have praise for Hajdu, but also have kind words for ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠Police Chief Adam Palmer. Some observers of your time in office might be surprised at that, considering your views on systemic racism within the police department, your strong words for the police union and budget fights with the VPD.

I very much respect Adam Palmer. I think he's one of the greatest assets of the City of Vancouver. Being the head of a police service is incredibly difficult. Drug users and their advocates have been pushing for [decriminalization] forever. The national association of chiefs of police issued their report in 2020 [to support decriminalization]. Adam Palmer was the president of the association at the time.

This is a big step for police. I was talking to a delegation from the U.S. that included a deputy police chief and his eyes just popped when I said that our top cop pushed for decriminalization. That's not a discussion you can have in many other places in North America.

Though the book focuses largely on drug policy and the history of its evolution in Vancouver, you do provide some insight into some city hall stuff that readers may be interested to read — namely why Sadhu Johnston announced his resignation in 2020. You say that he resigned because of increasing tension between him and councillors. Earlier in the book, you say he refused to stand with you when you declared a state of emergency during the early days of the pandemic. Do you think his resignation also had something to do with your leadership?

I think so in some ways. I say in the book that Gregor Robertson was a very good mayor for Vancouver. Now that I’ve sat in his seat for four years, I understand how tough the job is. Just the Broadway subway alone — getting that on the ground is a big, big accomplishment. But I think near the end of his third term, he left a lot more to the city manager to be independent. So where Gregor may have been focusing on other things, the city manager was increasingly coming up with policy ideas. I didn't see that as really what a city manager should be doing.

When I said, I'm going to go to the federal government and get money for housing, [Johnston] didn't believe me, and didn't really help. I was re-reading that part in the book the other night and thinking, ‘Oh, I hope that doesn't make him out as a bad person.’ It's just that the environment at work changed, and I had a very clear agenda that I wanted to implement. And I think he also had an agenda that he wanted to implement, and it led to tension.

You also tell a story in your book about “a local reporter” who “worked with opponents of mine who paid a struggling couple to set up a tent so as to block entry to the condo building where [my wife] and I rent, to generate a gotcha-news story when city staff asked the couple to relocate across the street.” That’s alarming on several fronts. I have so many questions. Let’s begin with who the opponents were.

I'm still finishing up one defamation case [involving the NPA], so I'm conscious of that. I don't think I'll name names at this point. But let's just say they've had successful political careers.

How do you know this couple was paid?

Park board staff interviewed these two folks and were told they were paid. They said the amount and the whole bit, and it was reported to the city manager, who contacted me and said they were paid to camp out in front [of the building] and positioned to make sure that where they were was illegal, and that the police would show up eventually.

I remember the incident making news, but had no idea about the background. So are you saying the reporter was in cahoots with these people who paid them?

Seems like.

Near the end of the book, you take a parting shot at Ken Sim, the man who convincingly beat you in the October 2022 election. Here’s the shot: “There is little hope Sim will champion new proactive measures to reduce the ever-increasing number of drug-related deaths in ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠or provide other services, such as social or affordable housing, as it will scare away his base. There is a very strong chance he will continue to more fully embrace criminalization and cruelty toward those needing the most help.” Sim has not yet served one year as mayor. Do you think your assessment is fair?

Well, the overdose prevention site in Yaletown — they've announced that that's being closed without a replacement.

¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠Coastal Health says it’s working with the City of ¬È∂π¥´√Ω”≥ª≠to find another site before this one closes next March.

It's not about finding a different location, it's about closing the overdose prevention site. In my four years, I worked very, very hard to get huge investments in social housing from the federal government and, later, the provincial government. I don't really see that kind of effort, but there's also probably not the knowledge.

When I asked him during a mayoral debate to name the housing ministers, he couldn't do it. Hastings Street. He took everybody's tents away. But everybody's still there, just in a much, much worse situation. So it's either complete naivety or just a lack of caring. People are continuing to suffer in the city.

Sounds like you’re in campaign mode?

I think about it. I’ve still got some time. In late 2019 [when I was mayor], I announced that I was going to run again. So this is about the time that somebody who's going to step up and push back needs to get there. And it's crickets. I don't see really anything on that side of things, and that really concerns me.

I'd love for [OneCity city councillor] Christine Boyle to come out this year and say she's running for mayor. That would be great because I think that she’s somebody people could get behind. Or maybe there's somebody else. I calculated that if you're going to go up against ABC Vancouver, you have to raise about $50,000 a month to match their spending starting now. You can't wait until six months out of the election, and then get crushed.

So am I going to be writing a story before the next election saying Kennedy Stewart wants to be mayor again?

Well, I can't guarantee you're not going to write that story.