The cold is a kind of teacher.

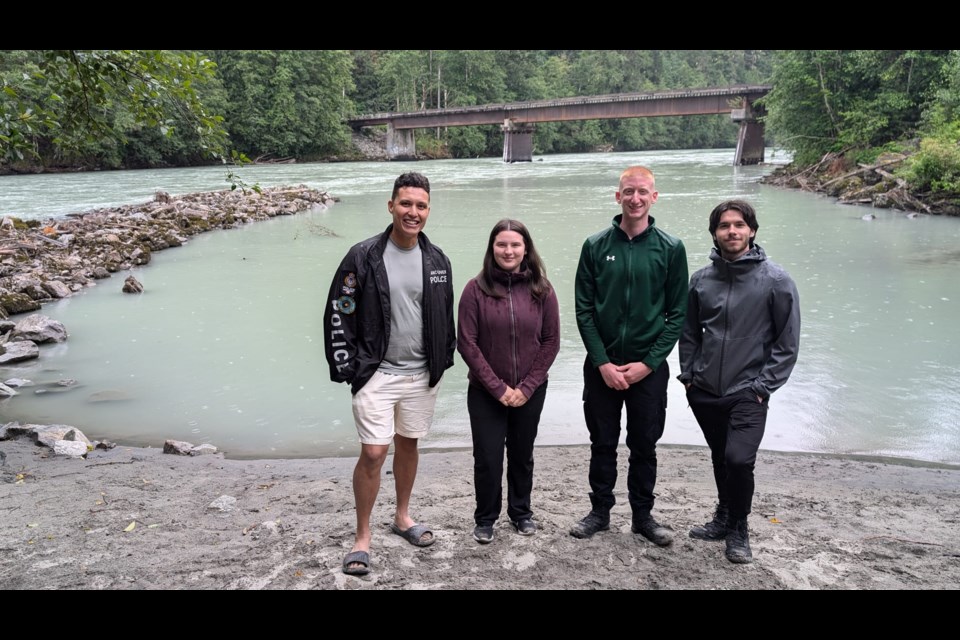

This week, on the remote banks of a Squamish river, Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Police Department Const. Freddy Lau stood shivering in the mountain wind with three Indigenous cadets and three fellow officers. They’d come to the Sea to Sky Corridor to experience a spirit bath, a ritual led by the department’s Indigenous protocol liaison, Rick Lavallee. Rocks had been arranged into position to create individual pools for them to plunge into, and it was time to dunk.

The glacial water was absolutely freezing.

“Rick explained to us why we do this. It’s about cleansing your mind, a sort of mind over matter thing. He coaches you through how to fight through it, and the more you do it, the easier it becomes. He used it as an analogy for life,” Lau told The Squamish Chief.

“If you come through an obstacle the first time, it’s tough, but the more these things happen, the more resilient you become.”

This is one of the life lessons Lau hopes to share with the Indigenous cadets he works with this summer. As a diversity liaison officer and co-ordinator of the Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Police Department (VPD) program, he’s tasked with exposing cadets to the many different facets of law enforcement—and that doesn’t mean just handing out tickets or going out on patrol.

The youth were given the opportunity to tour a courthouse, participate in the annual and help refurbish a sweat lodge.

They’re about three weeks into their program, which runs until Aug. 23.

It is a full-time paid position, and can act as a stepping stone for pursuing a career not only in policing, but in any vocation related to the law.

“In the beginning, we do an orientation where we educate them on the tip of the iceberg: legal use of force, radio etiquette, basically a crash course. During the Musqueam Canoe Races, they were helping out the community and driving Elders around, doing whatever needs to be done,” Lau said.

“Some days, we have guest speakers such as the major crimes unit, or forensics, the school liaison or maybe the gang crime unit. Last week in provincial court, they got a little taste of what court is like. They were able to see a trial from beginning to end, the cross-examination, how the lawyers argue.”

He’s seen firsthand how these experiences inspire the cadets.

“Some people who do this program may not be interested in law enforcement or considering a career in it. Some want to pursue one, but don’t know how. In our last class, two cadets ended up becoming community safety officers, and one now works full-time at the jail,” he said.

Lau feels awareness about the program is currently low, and he’d like to see more applicants.

“We’ve had this program for more than 15 years and I feel this program could be bigger. We do recruiting events, and our recruiting department reaches out to schools, and counsellors, but a lot of people still don’t know about it. At this point, a lot is just word of mouth,” he said.

Ultimately, Lau would like future cadets to join him on the banks of the river, just like this year’s cohort did. Learning from Lavallee's teachings, which involved songs and lessons from the river, Lau reflected on the fact that many Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»officers travel up the Sea to Sky highway to have these spirit baths or to bask in the sweat lodge and forget the stress and tension of the job.

This is one way that police officers are slowly strengthening their relationships with Indigenous communities in the time of Truth and Reconciliation, by learning about their customs and participating.

“I feel it’s important for us as police officers to listen and learn. It’s just as important as having people who are willing to teach. It goes both ways. I believe police can move forward and make things better with open communication and there has to be an effort on both sides,” he said.

“For me, it was a great experience.”

The program is made possible through funding from the Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Police Foundation and ACCESS Employment centre.

To learn more about the Indigenous cadets program,.