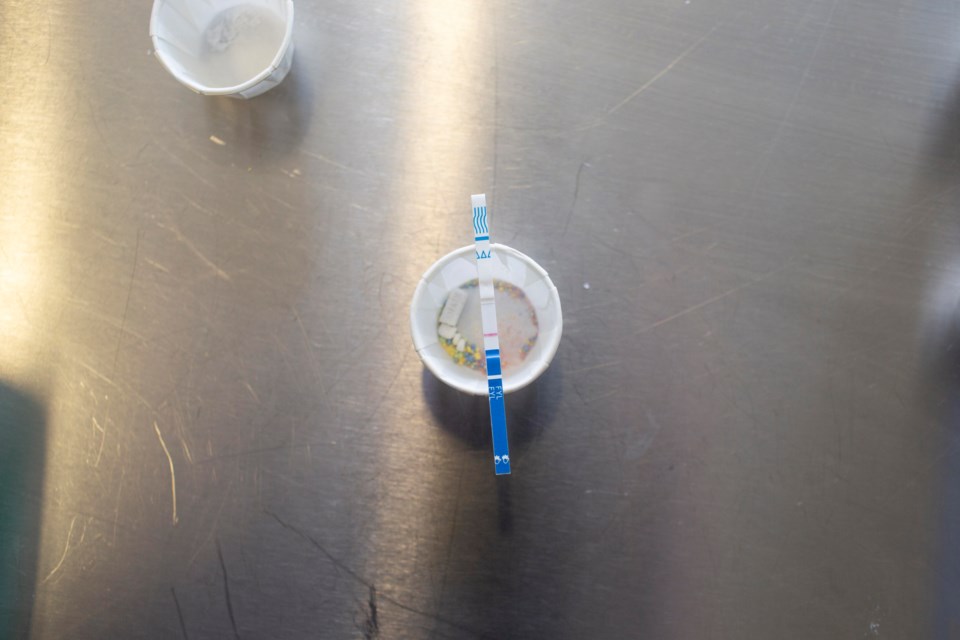

People who use drugs in Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»can use take-home strips to detect fentanyl in their supply.

But how accurate are the results from self-administered tests? And, perhaps more importantly, what is the likelihood that someone who uses drugs will use them?

A B.C. study finds that people who use drugs can detect fentanyl in their supply using take-home strips at positivity rates similar to those obtained by trained staff at harm reduction sites.

Among 1,768 opioid drug samples tested between April to July 2019, positivity rates for the take-home tests were around 90 per cent while those obtained by trained staff were 89.1 per cent.

The research study, , was conducted by Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Coastal Health (VCH), the BC Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU), the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC), Interior Health (IH) and the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) and published in the August 2022 edition of the International Journal of Drug Policy. The samples were collected from an area that comprised the Downtown Eastside and multiple smaller urban and rural communities.

Principal investigator of the study and Deputy Chief Medical Health Officer at VCH Dr. Mark Lysyshyn said over "80 per cent of overdose deaths in B.C. happened where people live" and the take-home strips provide a means for them to reduce their risk of drug poisoning.

Would the test program's participants use the strips again?

Since the pilot ran in 2019, VCH has made limited quantities of the take-home strips available at designated locations, such as supervised safe injection sites. Staff are available to ensure people who request the strips are familiar with how to use them.

In the study, the vast majority (95 per cent) of participants indicated they would use the take-home test strips again. Additionally, nearly one in three reported safer substance use behaviour as a consequence of a fentanyl positive test result.

"Drug checking, including the use of drug testing strips, is part of a broader harm reduction strategy employed by VCH and other B.C. health authorities, which allows an individual to identify the substances contained in illicit drug samples," explains a VCH news release.

Lead author and Associate Director with the BCCSU Clinical Addiction Medicine Fellowship program, Dr. Sukhpreet Klaire, told Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³» that the strips provide potentially life-saving information to people who use drugs in the space where they are most likely to use them: home.

While safe injection sites play a valuable role in harm reduction, "people don't always want to come into those spaces [to use] and [public health] may be missing people by only having those services situated in sort of physical settings," he explains.

Drug overdoses and fentanyl in B.C.

The study also showed most illicit substances in Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»likely contain fentanyl and "ultimately that is the drug [people who use drugs] need to use to prevent withdrawal symptoms."

But a positive result doesn't indicate how much fentanyl is in the drug — and the way a substance affects an individual depends on their tolerance. A small amount may be deadly for some individuals while someone who uses opioids regularly may tolerate a higher amount.

After using a self-testing strip at home, Klaire said some participants knew their drugs contained fentanyl, however, they exhibited "safer behaviours" after getting their test results.

Describing it as a "tool to use in a highly variable, toxic drug supply," Klair emphasizes that it won't prevent all overdose deaths.

"These findings demonstrate that in the absence of a regulated drug supply, strategies that provide people with information about the substances they're consuming are paramount to keeping them safe."

In 2023, British Columbia will remove criminal penalties for people who possess a small amount of certain illegal drugs for personal use — but experts say the exemption is largely political and will not solve the central issue: overdose deaths.

Find out why experts call B.C.'s new drug policy a 'zombie exemption.'