colinross1 Colin Ross, 37, continues to battle a heroin addiction while pushing back against stereotypes associated to drug users, the homeless and people living with mental illness. Photo Dan Toulgoet

colinross1 Colin Ross, 37, continues to battle a heroin addiction while pushing back against stereotypes associated to drug users, the homeless and people living with mental illness. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Being Colin Ross can be complicated.

His 37-year-old life, as far back as he can remember, has been this way.

Why?

Itās a long story.

But to tell it, the former chef wants you to reconsider the first impression you may have of him after studying his photograph: yes, heās a heroin user, looks a little rough and is one of those determined guys who roots through dumpsters for discarded goods that he turns into a profit on the street.

Sit him down in a Main Street cafĆ©, with a coffee in front of him, and the Edmonton-born, Canmore-raised āhurtinā Albertanā will tell you thereās more to his life than a dependency on drugs and the grind of binning and vending.

Ross lives in a subsidized apartment in the West End, where he creates art with some of his dumpster finds. He remains connected with his sister in Kerrisdale and regularly visits his niece and baseball-playing nephew.

Then thereās his long-held passion ā educating students, doctors, politicians and others interested in his life as a drug addict. He estimates heās done at least 60 talks in eight years at schools and conferences.

The sharing of his story was inspired by his membership with the Mayorās Task Force on Mental Health and Addictions, the cityās advisory committee of people with lived experience and his participation in the Mental Health Commission of Canadaās At Home/Chez Soi housing experiment and speakersā program.

In April, he spoke to city council on behalf of Megaphone Magazine to help secure an $85,000 grant to set up a speakersā bureau. The goal is to continue the work of the At Home program, his work with the city and focus on removing the stigma many in the public attach to drug users, the homeless and the mentally ill.

āIām very passionate about changing the way people look at people who are struggling,ā he said in one of a series of interviews with the Courier in recent months. āIām a decent person and a drug user. It doesnāt have to be two different things.ā

Trust him, he said, he didnāt choose to lead the life of a drug addict. That reality can be traced to an untreated bipolar disorder, severe anxiety and having alcoholic parents who separated before his first birthday.

Depression, anger, isolation and going through his own bout of alcoholism have been other experiences. Ross, who had a criminal record as a juvenile in Alberta ā mainly for petty stuff such as shoplifting and vandalism ā has lived on the streets and overdosed once.

He himself is amazed he's still lucid, still here.

The frequent illicit drug death reports from the BC Coroners Service suggest Ross is vulnerable: the largest group of people dying from drug overdoses are white men in their 30s, who have had a long history of addiction.

So much of the reporting about the opioid crisis has focused on the dead.

Ross is a survivor.

How has he done it?

The answer involves a caring sister, a good doctor, finding his own apartment, trying a variety of treatment options, being asked to share his story with people in power, some luck and an internal drive to stay alive.

That drive, as well as some of the frustrations of managing an addiction, was evident on the days the Courier accompanied Ross to a pharmacy, a doctor's appointment, on walks through the Downtown Eastside and visits to coffee shops.

What follows is a chronology of sorts, beginning in April and finishing in July, that provides a glimpse into the life of a man who doesn't know that he'll ever be drug-free, but is determined to get stable and be more present in the lives of others.

āWarm hug from Godā

In the back room of Pier Health Resource Centre, near Main and Hastings, Ross is sitting in a chair as nurse Amanda Pelcz prepares a dose of liquid hydromorphone, a pain management opioid designed to reduce cravings for heroin.

It's a mid-morning on a Thursday in late April. The sun is out and Rossās bike ride from his West End apartment has left him wiping his brow with paper towel.

Ross is one of 53 participants in the pharmacy's injectable hydromorphone program. He became a patient in June 2017. Twice a day, he injects himself under the supervision of a nurse. Then he takes an oral dose of hydromorphone in the evening at his neighbourhood Shoppers Drug Mart.

Itās a daily routine that he admits can be onerous, but has substantially decreased his dependence on heroin. Itās also meant he doesnāt have to spend as much time binning to pay for his heroin habit, which at its high point can reach $40 a day.

āWhen you see people beat to shit, itās because of what youāve got to do to get the drugs,ā he said. "Coming in here, I deal with a pharmacist and a nurse as opposed to some dealer in a piss-smelling back alley. Itās a completely different atmosphere, which puts you in a different head space. It gives you some dignity, is the other thing.ā

Colin Ross at the Pier Health Resource Centre near Main and Hastings, preparing to inject liquid hydromorphone into his arm. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Colin Ross at the Pier Health Resource Centre near Main and Hastings, preparing to inject liquid hydromorphone into his arm. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Ross takes the syringe from Pelcz and injects 50 milligrams of hydromorphone into his tattooed left arm. He gives the drug a few moments to take effect before he explains the sensation.

āThereās a little initial rush, which I like to call a warm hug from God,ā he said. āItās like a deep breath. All your muscles ā everything ā is relaxed. Itās like a sigh, a full body sigh.ā

But itās not heroin, which he developed an addiction to as a teenager.

āGood heroin would do the same thing in a lot ways, but do it way better. Like decaf to real coffee.ā

Over the years, Ross has tried methadone, Suboxone and a steady oral dose of hydromorphone, which doesnāt produce the euphoria experienced with injection.

None, he said, has been as effective as heroin in treating his mental and physical pain; he has arthritis in most of his joints and various other nagging injuries.

Ideally, he wants to try diacetylmorphine, which is medical grade heroin. The Crosstown Clinic, located a few blocks from the pharmacy, is the only clinic in North America that offers the drug to chronic drug users.

Ross has expressed a desire to his doctor, David Tu, to become a patient. But the popularity of the program, which has seen impressive results where patients have stabilized enough to secure housing and jobs, has meant a long waiting list.

Tu is the reason Ross is more stable than heās ever been. It is difficult for Ross to talk about his doctor without getting emotional. On the advice of a friend, he searched out Tu more than seven years ago, who took him on as a patient.

āHeās a saint, he saved my life,ā Ross said after taking the required 15 minutes in the pharmacyās waiting room to relax and ensure heās showing no ill effects from the hydromorphone. āHeās a wonderful doctor, just a good human being. He really understands addiction. Heās done a lot of good for a lot of people.ā

āTherapy is a bridgeā

It was Tu who got Ross into the pharmacyās injectable hydromorphone program, which was developed by colleague, Dr. Christy Sutherland, the medical director of the PHS Community Services Society.

Sutherland entered into a partnership with Pier owner, Bobby Milroy, to set up the innovative and ground-breaking service, which provides another treatment option for those unable or not interested in accessing the Crosstown Clinic.

āYou end up helping a group of people who would not otherwise be allowed to be helped,ā said Milroy, standing outside the pharmacy on the day of Rossās visit in late April. āAs a result, youāre saving lives. It doesnāt work for everyone, and I donāt think it will be everyoneās choice of treatment, but itās simply one more option.ā

Ross was Tuās first patient to participate in the pharmacyās program.

Dr. David Tu meeting in his office with Colin Ross. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Dr. David Tu meeting in his office with Colin Ross. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Over lunch at a restaurant adjacent to his office at the Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»Native Health Society on East Hastings, where he sees about 70 patients on drug replacement therapy, Tu explained the referral.

He reiterated what Ross said about methadone, Suboxone and oral hydromorphone not providing the results they both hoped for.

āNone of that allowed him to not continue to use injectable street opiates,ā Tu said. āAnd when youāre injecting on top of whatās being prescribed to you, youāre going to develop a higher tolerance and experience those same withdrawal symptoms. So youāre not going to get that stabilizing.ā

For some context to Ross's situation, Tu recounted a brief history of opiate replacement therapy in the United Kingdom, Switzerland and other parts of Europe, which have been progressive on drug policy and harm reduction initiatives for years.

But what the body of literature concluded in those countries' experiments, and holds true in North America, is that about 10 per cent of addicts will not stabilize by oral therapy alone.

Diacetlymorphine and injectable hydromorphone were found through various studies to be the only option for that 10 per cent.

Tu pointed to the North American Opiate Medication Initiative, more commonly known as the NAOMI trials, which revealed almost 10 years ago that study participants in Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»could not accurately discern the difference between the effects of diacetylmorphine and injectable hydromorphone.

Hence the reason to get Ross started on the injectable hydromorphone program.

āThereās going to be five to 10 of my patients at one time that are not successfully stabilizing on oral for whom youāve got to look for something else,ā Tu said. āIt doesnāt make sense to keep on trying something thatās not working.ā

Tu said Ross experienced a ādramatic turnā in the first four months of his therapy and found the hydromorphone helped him stabilize and focus on his work in the harm reduction community.

The goal was to free Ross, whose monthly welfare cheques help pay for his rent, food and phone bill, from the stress of binning and vending, effectively decreasing his use of heroin.

āHeās starting to see himself as a good person, someone who can contribute,ā he said. āAnd when he has that, it will drive him to make choices that will likely be more positive and affirming, and put him on a good path.ā

Tu continued:

āThe therapy is a bridge ā hopefully ā to some sort of transformation. It can be a very long bridge, it could be a shorter bridge. But itās a means to an end, as opposed to an end itself.ā

āYouāre always playing Russian rouletteā

The path of that bridge took a turn two weeks after the Courierās interview with Tu.

Ross was no longer participating in the injectable hydromorphone program. The hydromorphone was āmaking me feel really gross, which is really weird because Iāve always liked it.ā

The routine of having to bus or bike to the pharmacy twice a day was also grinding him down. He had been doing this for almost a year, living a life where he was tied to the pharmacy.

Thatās what he told Tu during an appointment in mid-June. A few weeks prior, Tu prescribed long-acting morphine capsules for Ross, which cut back his visit to a pharmacy to once a day.

Tu to Ross: āHow do you feel about continuing on the long-acting morphine?ā

Ross, sitting in Tuās office: āItās not ideal, but I wouldnāt say itās upsetting me or anything like that.ā

The conversation shifted to talk about the Crosstown Clinic and diacetylmorphine. Ross agreed to visit the facility while Tu would again try to get him in the program.

Ross: āIāve actually never been in there, but I think I know a lot of what goes on. Iāve never done diacetylmorphine, but Iām assuming it would be something Iād like more.ā

In the meantime, Ross hoped to get a prescription from Tu for several doses of long-acting morphine that he could take with him on a week-long trip to northern Alberta. He was feeling stable enough to return to his home province to attend a music festival.

His father, who had remarried and had kids, would be there. So would a lot of friends. He needed to recharge, he said, and get out of the city for a while. He raised money through a GoFundMe campaign for a plane ticket; two relatives donated the money.

Tu agreed to write a prescription, but had more questions for Ross.

Tu: āHow has your stress level and mood been over the last little while?ā

Ross: āFor the most part, pretty good. Iāve been a little stressed out and kind of pissed off a bit, but itās been in the face of things that would really stress anybody out.ā

Tu: āYeah.ā

Ross: āI havenāt been off the deep end. I havenāt had a day where I was really feeling uncontrollably angry just for being angry, or being set off and not being able to calm myself down.ā

Tu: āSo youāve been able to maintain a kind of equilibrium?ā

Ross: āYeah.ā

Tu: āMore good days than bad days?ā

Ross: āFor the most part, itās been pretty good to be honest.ā

Tu reminds of him of the contaminated drug supply that killed 365 people in Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»last year, and has killed 165 in the first five months of this year. More than 1,400 people died across the province last year, with the majority of deaths linked to fentanyl.

Rossās response to Tu, and one he repeated to the Courier several times, is that heās careful when using drugs. He uses injection sites when there are no lineups and always uses a small amount of heroin for his first injection. He ensures he's around people equipped with the overdose-reversing medication, naloxone.

Even so, Ross overdosed about a year ago in an alley outside the Washington Hotel, near Main and Hastings. He regained consciousness in the hotel's injection room, before being transported by ambulance to St. Paul's Hospital.

āYouāre always playing Russian roulette, but for me itās as close to playing with a gun full of blanks," he said, describing his overdose as "minor" and believes to this day the naloxone wasn't necessary. "I never say Iām not taking any risks, but Iām as risk-free as you can possibly be.ā

Bir Kaur OāFlaherty, Colin Rossās sister, became a guardian to her brother when he was 15. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Bir Kaur OāFlaherty, Colin Rossās sister, became a guardian to her brother when he was 15. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Special bond with sister

His sister, Bir Kaur OāFlaherty, has heard him say that a lot ā that heās careful, not to worry, heāll be fine.

It's little comfort for someone who pays attention to the news and hears story after story about the opioid crisis and how it's devastated families across the province.

"It only takes one time, and that's it," she said, sitting on a sofa in a cafe at the Jericho Village shopping centre. āBut I have a practice and belief in my life that if he's going to die, he's going to die. I would, of course, be devastated, but it doesn't matter what I do to not make it happen, I just have to let it go."

The siblings have a special bond, with OāFlaherty taking responsibility for her brother when he was 15; she was 18 at the time, and recently moved from Alberta to Commercial Drive.

She has watched her brother get entrenched in a drug lifestyle, argued with him about it ā which resulted in long stretches of not talking to each other ā and tried to get him help.

A few years ago, she was successful in helping him get into Onsite, the detox centre above the Insite supervised injection site on East Hastings; Ross has been through various detox centres in B.C. and Alberta at least seven times.

She's listened to him, offered advice and has been like a mother to her brother.

Ross often jokingly refers to his sister as the āblack sheepā of the family. Sheās married, with two young children, lives in Kerrisdale, works as a doula, an administrator at a midwives centre and teaches yoga.

The siblingsā mother, Jackie, lives in her basement.

Colin Ross with his sister, Bir, and parents Jackie and Colin in an undated photograph. Photo courtesy Bir Kaur OāFlaherty

Colin Ross with his sister, Bir, and parents Jackie and Colin in an undated photograph. Photo courtesy Bir Kaur OāFlaherty

Ross has had a challenging relationship with his parents, but said he is now close with his mother. His father, also named Colin, is still in his life, however tenuous the connection may be.

But itās always been his sister heās leaned on, which he again did a couple of weeks ago.

That trip to Alberta he was looking forward to?

He didnāt make it.

He called his sister in tears somewhere between Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»and the Abbotsford International Airport. He missed the last afternoon bus to the airport by eight minutes. The plane left without him, and he was unable to recoup any of the money he spent on the ticket.

āIt was shitty, just really shitty and it was the first time I'd been worried about him in a long time," she said. "He turned his phone off and I didn't hear from him for two or three days."

He eventually showed up at her son's baseball game, where he took his niece to a playground. He didn't look as rough as she thought he would. He seemed content, happy to be there.

"What I came to realize probably a good eight or so years ago is that my version of OK and his version of OK are two very different things,ā she said. āSo for me to look at his life based on what that would feel like for me, it's very not OK. But for him, when I look at where he is now, he's doing spectacularly well, comparatively."

That's when the conversation turns to Dr. Tu, whom she described as amazing. His quality of care convinced her that Ross is in good hands. Without Tu, without the treatment options, his subsidized apartment, the advocacy work, O'Flaherty is confident her brother would be dead.

"Like a long time ago," she said.

If he were a boy in todayās world, OāFlaherty believes her brother would be on a different path. As a child, he was hypersensitive, intelligent and talented. He was bored in school.

āThey know about this now, and deal with it differently,ā she said

OāFlaherty continues to have hope for her brother. He is showing signs of being more present and more comfortable in his own skin.

"In some ways, he's doing better than I've ever seen him doing. The anxiety has really lessened by quite a lot, and he's able to be open and honest with my mom and me with what's happening in his life."

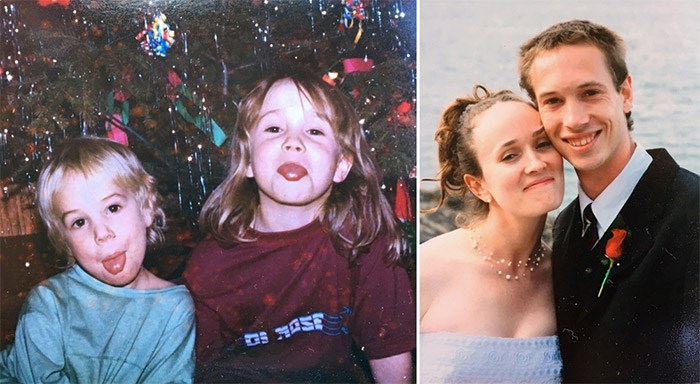

Colin Ross and his sister, Bir, as young kids and on Birās wedding day. Photo courtesy Bir Kaur OāFlaherty

Colin Ross and his sister, Bir, as young kids and on Birās wedding day. Photo courtesy Bir Kaur OāFlaherty

One day at a time

So what happens next for Colin Ross?

Last week, over coffee at a Main Street cafe, he said he hadnāt slept in three days. He was still taking the long-acting morphine, but was continuing to use heroin.

Evidence of that was his drug dealer buzzing his phone with text messages.

He talked a little bit about his failed trip to Alberta, shaking his head in disgust as he explained what happened.

āSo I spent a whole bunch of money to go to Surrey for the day,ā he said. āThat was my vacation. It was a big, big letdown.ā

Heās still waiting to hear from Megaphone Magazine about the speakersā bureau. Heās likely to get more speaking gigs via the cityās lived experience committee when school is back in session. His doctor also talked about having him speak at his kidsā school.

He needs a purpose, he said. Idle time is not good for him.

While heās talking about what he needs, he wants more to be done on the treatment front for drug users. Donāt get him wrong, he said, he is grateful to live in a city and province that is progressive in its drug policy.

But why isnāt there more widespread availability of medical grade heroin? Why canāt he take prescribed drugs home with him? Why does he have to be tied to a pharmacy up to three times a day?

Ross understands not every drug user can be trusted in a take-home program. But then, he said, assess each personās situation and create a plan that works for the individual, not hinders efforts to get better.

Because right now, he said, nothing beats the high he gets from the heroin he buys in the streets, where hundreds have died.

Will he ever be abstinent?

āI was thinking about that the other day. If things I need to happen in my life happen, and I can move forward, then I do see abstinence in my future. But if I spend another couple of years in this situation, Iām starting to get dug in and I donāt know that Iāll ever get out.ā

For now, itās one day at a time.

āIāve accepted myself for who I am, and Iām trying to make the best of it,ā he said. āMaybe my life is supposed to be silver, not gold.ā

@Howellings