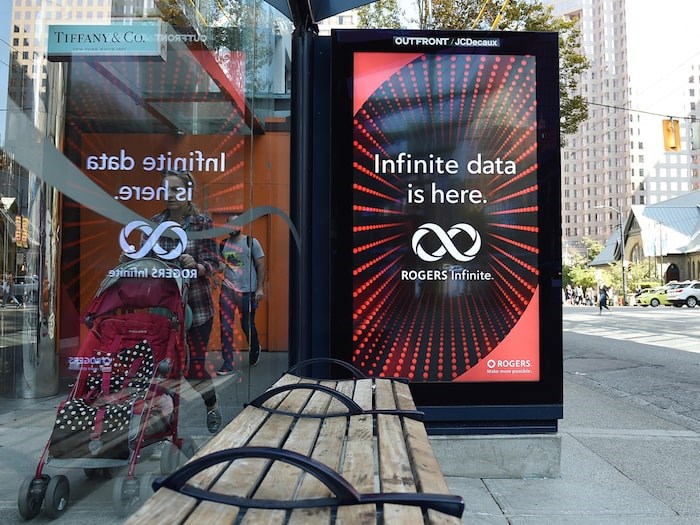

A bus stop shelter on Burrard between Alberni and Georgia has camera’s built into its video screens. Photo by Dan Toulgoet

A bus stop shelter on Burrard between Alberni and Georgia has camera’s built into its video screens. Photo by Dan Toulgoet

Next time you’re at a Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»transit shelter with a digital advertising sign, look closely at the sign’s frame. At eye level, you’ll find a thumbnail-sized camera.

Your bus stop is watching you.

“There’s definitely laws being broken here and a lot of questions about who is using the cameras and collecting the information,” said BC Civil Liberties Association acting policy director Meghan McDermott.

And, said the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner (OIPC), neither transit officials nor City of Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»officials alerted the office to the cameras.

“We were not aware of this matter and are now actively looking into it,” commissioner Michael McEvoy said.

In a shelter such as one opposite the Hotel Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»on Burrard Street there are four cameras. While some passers-by shrugged them off, one woman called it “creepy.” Everyone asked identified the small squares as cameras.

But there is no signage telling people of the cameras’ presence, another red flag for McDermott.

“It’s very clear in provincial law that for a camera like that, consent is required,” she said. “Unless the cameras are not operational, we sure have a situation where people’s privacy is being breached illegally. It’s very concerning that this is going on.”

A commissioner’s office statement said the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) requires an organization to inform people if it is collecting data – which includes photographic images that can be used to identify people through photo recognition software.

“Under PIPA, an organization usually cannot collect personal information unless they have an individual’s consent,” the statement said.

Vancouver’s shelters are provided by Outfront Media and JCDecaux, which in partnership supply and maintain street furniture in Vancouver. The partnership does so in exchange for rights to the transit shelter advertising, the City of Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»website said.

A bus stop shelter on Burrard between Alberni and Georgia has camera’s built into its video screens. Photo by Dan Toulgoet

A bus stop shelter on Burrard between Alberni and Georgia has camera’s built into its video screens. Photo by Dan Toulgoet

Neither France-based JCDecaux director of communications Agathe Albertini nor head of investor relations Arnaud Courtial could be reached for comment.

What is clear is that JCDecaux has made significant advances in the use of bus shelters for advertising using so-called augmented reality involving image projections and cameras in shelters. One eye-popping Pepsi project in the U.K. capital, featured UFO’s and wild animals as well as the people watching the images. The London project . The presence of a camera in the shelter is readily noticeable.

Other companies have acknowledged cameras are used to profile customers using facial recognition.

Samsung, for example, said as part of its augmented reality campaigns, “cameras would detect the audience profile, which consisted of age, gender, expression, composition, and engagement. Based on that profile, one of the thirty videos would play to engage the prospect.”

The current contract between JCDecaux and the city was signed in July 2003 for a 20-year term, although a deal was in place for more than a decade before that, replacing a contract with a Jimmy Pattison company. The contract shows a guaranteed minimum revenue of $29.5 million over the term.

The city shares in revenue from the advertising, which is permitted only on modular bus shelters and automated public toilets.

The contract says the city general manager for engineering services must approve all design elements for the infrastructure.

And there’s a potential for anywhere between 675 and 900 shelter locations throughout Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»or a minimum of 1,380 ad panels, the contract said.

The document also contains provisions for electrical data connections for which the city shall not be charged.

While the OIPC has no process for approving or allowing cameras or other technology on public infrastructure, it does regulate the collection, use and disclosure of personal information by public bodies and organizations, including images captured by video cameras.

“In other words, a public body or organization may choose to install a camera, but any personal information collected must comply with the privacy laws that we enforce,” the OIPC statement said.

It said any data captured by such cameras is subject to the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act in the case of public bodies and PIPA in the case of other organizations. “Both set out limits on collecting, using and disclosing personal information, as well as requirements on keeping in secure and providing for a right of access, among other requirements,” the statement said.

City spokeswoman Ellie Lambert said officials are looking into the situation and expect to have some answers next week.

TransLink officials would not say if authorities were aware of the cameras targeting their passengers or if the advertising company had alerted them to the cameras’ presence.

“Metro Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»bus shelters are owned by the various municipalities in the region,” senior media relations advisor Ben Murphy said. “They are responsible for any decisions relating to the operation of bus shelters.”

McDermott said there have been problems in the past with TransLink sharing data on people’s travel patterns it has collected with law enforcement without court warrants.

“The collection and use of this footage and passage of that to law enforcement is extremely troubling.”

This is not the first time Canadians have found themselves targeted by cameras for commercial purposes.

In 2018, it was revealed that mall operator Cadillac Fairview had cameras installed in shopping centre digital maps in Calgary. The cameras were recording information such as shoppers’ ages and genders.

McDermott said the bus stop situation is similar.

“As technology is getting better and better, it’s going to be easier and easier to hide this kind of surveillance,” she said.

This story has been updated to include comment from the City of Vancouver