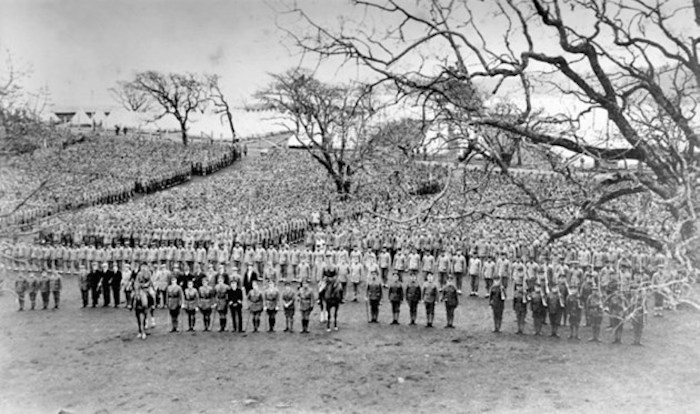

A parade drill led by the 5th British Columbia Company of the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery, charged with imposing discipline on the recruits. Photo via Metchosin School Museum

A parade drill led by the 5th British Columbia Company of the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery, charged with imposing discipline on the recruits. Photo via Metchosin School Museum

They laid 21 ghosts to rest near Victoria on Halloween.

Amid the Garry oaks of an old cemetery on the grounds of William Head prison, nestled between Juan de Fuca Strait and the building where the inmates lift weights, a memorial was unveiled Oct. 31 to a score of previously unidentified men who died there after travelling halfway around the world.

Prisoners? No. They were Chinese labourers, 85,000 of whom passed through William Head southwest of Victoria en route to Europe and the First World War.

You haven’t heard that story? Never mind. Few have. It was intentionally kept quiet, which is why those 21 men were all but forgotten for a century.

The tale goes back to 1916, when William Head was a quarantine station for people arriving in Canada by ship, and when, far away in France, war casualties were piling up at a ghastly rate.

The British government approached China with the idea of recruiting men to serve as non-combatants: building roads, fixing gear, digging trenches, that sort of thing. The idea was to allow the troops who had been doing those jobs to replace the front-line soldiers who had already been fed into the meat grinder of the Western Front.

“It freed more men to be blown to smithereens in the trenches,” is the way Peter Johnson, author of Quarantined: Life And Death At William Head Station, 1872-1959, put it Thursday.

China agreed to Britain’s request, but only if the scheme was kept under wraps; China was anxious not to be seen as breaking its neutrality. So when Canadian Dr. Harry Livingstone — the grandson of explorer David Livingstone of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume” fame — shepherded 85,000 men of what was known as the Chinese Labour Corps here, it was done on the down-low.

Ships like the Empress of Russia would disgorge them, thousands at a time, at William Head. There they lived in bell tents before being taken to Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»and locked in sealed trains for an eight-day journey to Halifax, where they boarded vessels bound for Europe. Ottawa, which had implemented a head tax to discourage Chinese immigration, didn’t want the men escaping and didn’t want the citizenry to know they were here.

“It really was a hush-hush thing,” Johnson said. “William Head was a perfect location. It was out of the way and essentially off limits.”

What France had in store for the labourers, many of them impoverished peasants recruited from northern China, wasn’t what was promised.

“They went into a horror story,” Johnson said.

Being non-combatants didn’t save them. Many ended up working at the front, where falling shells didn’t discriminate in their targets. Even after the war, it was the Chinese who had the grim, dangerous job of clearing the battlefields of corpses and unexploded munitions.

Some of the labourers didn’t even make it to Europe, or didn’t return all the way home after the war. They’re the ones who died, mostly of disease, at William Head.

The Old Cemeteries Society website says 49 people are buried there. They include merchant seamen and a couple of young soldiers who died in 1919 on the way back from Siberia, where Canadian troops had been sent to fight the Russian Bolsheviks. Most of the dead — 35 of them, according to the website — were Chinese labourers.

The thing is, only five of the Chinese were identified by name. Most were listed only by a labour corps number, their precise location within the cemetery unknown.

They would have stayed anonymous had the U.K. headquarters of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission not begun pressing to have the labourers treated as war dead of the British Army, to which they were officially attached.

That led Ottawa-based Dominique Boulais, of the commission’s Canadian office, to dive into archival documents, meticulously piecing together the puzzle. With the aid of the likes of former William Head librarian Kim Rempel, a picture emerged.

In addition to the five labourers already identified on grave markers, Boulais et al were able to name 21 others buried in the old graveyard. There may be more, but these are the ones who they are certain of, ranging from Wei Chen Shan, who died on July 17, 1917, on the way to the war, to Hsieh Shou Ch’ing, the last of those to perish on his way back home.

A memorial for 21 men buried on the grounds of Metchosin’s William Head prison was unveiled Thursday. They were among 85,000 Chinese labourers who passed through on their way to the First World War. Photo via Dominique Boulais/Commonwealth War Graves Commission

A memorial for 21 men buried on the grounds of Metchosin’s William Head prison was unveiled Thursday. They were among 85,000 Chinese labourers who passed through on their way to the First World War. Photo via Dominique Boulais/Commonwealth War Graves Commission

These were the kind of men who became real to Johnson as he researched his book. “There were some very poignant letters home,” he said. These weren’t warlike people, just poor ones desperate to feed their families in China. While waiting at William Head, the Chinese would make trinkets for the children of the quarantine station’s staff.

On Thursday, in a brief ceremony at the cemetery, that memorial to the 21 men was unveiled, listing them by name. No longer would they rest in what Boulais called “an impersonal, faceless tomb.”

Among the small crowd was a contingent of aging Chinese-Canadian war veterans who stood and saluted as The Last Post was played. Behind them, a few deer grazed placidly in a field where century-old photos showed thousands of long-forgotten Chinese men massed in ranks, waiting to go to war.