Private George Agustus Johns was six-feet tall with a ruddy complexion, blue eyes and brown hair, and at 27, he’d signed up to fight in Siberia just as the First World War in Europe was coming to a close.

Johns would never make it.

Somewhere between his army base in Borden, Ont., and the CPR railyard in Port Coquitlam — a waypoint on the way to Russia — the young army teamster was among the first in B.C. to come down with the Spanish flu — a highly virulent strain of the H1N1 virus that would snuff out the lives of between 50 and 100 million people across the planet and go down as the most deadly virus in history.

Johns stepped into the railyard with eight days to live. Like the rest of the other roughly 3,000 soldiers who made up the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force, Johns was getting set to ship to Vladivostok as part of a multi-national force tasked with securing a supply line for Tsarist Russia during the Bolshevik revolution.

Within days, his first symptoms would have come on suddenly, a sharp pain in the back or joints immediately debilitating him before a wave of dizziness spun him into a delirium of fever and chills.

As the days wore on, a secondary infection would have begun in Johns’ lungs with the onset of pneumonia and no antibiotics yet in existence to ward it off. His skin would likely have turned blue as it went cyanotic. By 5 a.m., Oct. 10, the young private’s lungs had filled with enough fluid to .

A FOREIGN THREAT COMES HOME

Canadians first heard of the Spanish flu from dispatches a world away. As the Allied armies advanced on German positions in the summer of 1918, the silent killer started making headlines at home.

On June 29, 1918, the 麻豆传媒映画Daily Sun published dispatches from the European front reporting a ‘Hun army’ unable to fight, prostrated by an influenza epidemic known locally as the ‘Flanders grippe.’

Still, it was a far-away threat, and as late as Aug. 15 that same year, the 麻豆传媒映画newspaper reported that there was “no ground for the general fear that the outbreak of Spanish grippe which has ravaged Europe will spread to this city.”

Few on the West Coast could have known that the fated troop carrier train, which rolled out of Sussex Camp in New Brunswick on Sept. 27, 1918, did so on the same day the base reported its first cases of the flu, according to historian Mark Humphries. When Johns came aboard at Borden, Ont., he, like the rest of the soldiers aboard, knew little of the germ theory which governs the spread of a virus through droplets in one’s breath.

As the train rolled through the Prairies, soldiers disembarked in towns and cities like Winnipeg and Calgary, seeding local outbreaks across the Canadian west.

“Because they knew that they would be shipping out, they said goodbye to family members. That distributed the flu into many small communities,” said Mary-Ellen Kelm, a historian at Simon Fraser University who has tracked the effects of Spanish flu in British Columbia.

By the time the train pulled into the railhead at Port Coquitlam, the soldiers — packed into the overcrowded cars — had already started to show symptoms of the illness.

CONTAINING THE CONTAGION

The first case was reported Oct. 1, and by the next day, the entire troop train was under quarantine at the CPR yard. From that moment, Port Coquitlam would become an early battleground in the fight against the Spanish flu.

In a desperate attempt to contain the contagion, the military commandeered the city’s agricultural hall, or ‘Aggie Hall,’ on Oct. 12, the same day Johns’ death was first made public in the Coquitlam Times newspaper.

“Private Johns succumbed to the disease Thursday and will be interred at Westminster,” it read.

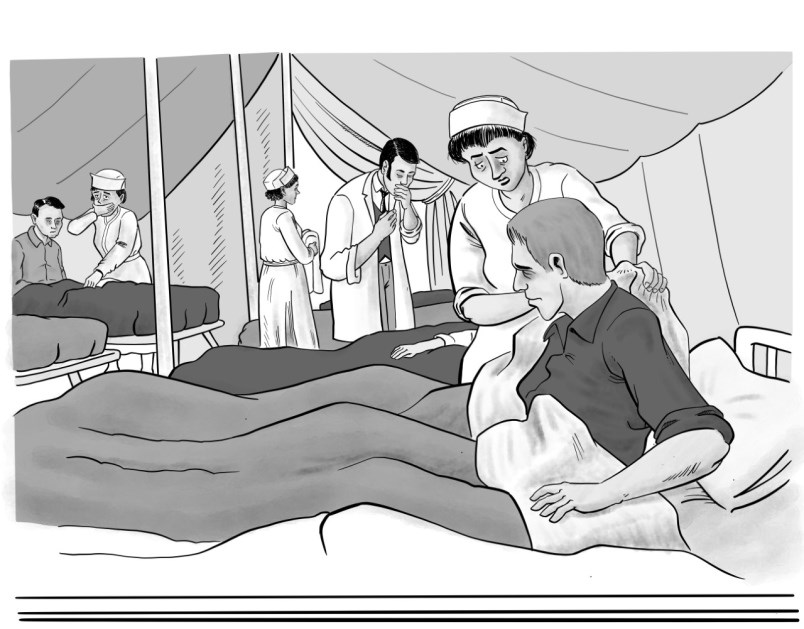

Soon the makeshift hospital filled with so many sick soldiers that patients overflowed into tents on the surrounding lawns.

Not unlike some of the measures suggested today with COVID-19, the Times went on to state the civilian population should “avoid travelling in closely confined carriages” and take part in “plenty of open air exercise with scrupulous care of mouth and throat.”

Soldiers were put on a mandatory lockdown as a no-go perimeter was erected around the building, according to the Times. But with so little known about the spread of viruses, the overcrowded field hospital — like so many across Canada and the world — would trigger an outbreak across the region.

“They couldn’t do much but set up convalescent nursing stations,” said Kelm. “They quickly ran out of nurses because nurses and doctors were some of the most affected.”

But while today personal protective equipment has at times been tough to come by amid the COVID-19 pandemic, in 1918 it was nearly non-existent. Without a powerful enough microscope, no scientist had yet seen a virus, let alone calculated the spray radius of virulent droplets.

Still, upon the virus’s arrival in the Lower Mainland, the tone in the Vancouver-area press went from one of disbelief that the contagion could ever hit its communities, to a state of general lockdown. “Doctors said to be preparing for the worst,” warned one newspaper on Oct. 1, as reports came in from Montreal that schools, picture shows, dance halls and public theatres were to be shuttered.

Public health advertisements cautioned all ages of the dangers of wet feet and spitting in public, and in special advisories to children, health officials warned not to “lick off another child’s sucker,” bite another child’s apple and, “Boys, don’t lick your marbles.”

But it was too late, the virus was already amongst the population, spreading with asymptomatic soldiers along the rail lines and into Vancouver’s core.

“You can literally track where soldiers went and where they visited,” said Kelm.

THE SURGE

Within weeks of the train’s arrival, 麻豆传媒映画school gymnasiums and community centres turned into makeshift hospitals as caseloads surged.

The virus reared its head in North and South Vancouver; soon, 700 cases were reported in the capital of Victoria.

A found that almost half the people thought to have died from Spanish flu in 麻豆传媒映画did so at home, and most of those were pinpointed to addresses stretching from Gastown to the Downtown Eastside and Strathcona neighbourhood, a densely populated area just north of the railyards.

As the scope of the outbreak became apparent, public figures delivered often conflicting messages to deal with the contagion — sometimes with bizarre pronouncements.

By October 1918, health officials said it was impossible to quarantine people to their houses as “it would take an army to do the placarding.” Instead, the 麻豆传媒映画Daily Sun appealed to the public to look to the virtues of the outdoors. “Fresh air may be a foe of the grippe — call it Spanish Flu or the slippery sneeze from Timbuctoo if you want to — but a draft is its best friend,” the newspaper printed on Oct. 11.

At the Coquitlam Military Hospital at Aggie Hall, where the country air offered such “drafts,” over 160 soldiers had fallen ill, and by the end of the month, it would jump to 396, a massive spike in a town of no more than 1,200 people.

Soon, reporters at the Coquitlam Times newspaper had become suspicious of the state of the outbreak.

“There seems to be a lot of puerile secrecy or a perverted conspiracy of silence in regard to the epidemic that can serve no good purpose. It is well that the public should at all times know the true state of affairs in regard to such matters,” wrote the Times in an Oct. 12 report.

Five days later, city council ordered the “closing tightly” of the local theatre, churches and public meetings. Fraternity clubs were shut down and parents were asked to keep their children away from playmates and confined to their homes. Public buildings, like the post office and railway station, as well as the shipyard bunkhouses, were fumigated as the publicly disclosed civilian caseload jumped to 13 in Port Coquitlam (it’s unclear how many were ultimately infected and died). Even dog owners were told to rein in their pets or else they’d be destroyed.

“Tie up Fido or annihilate him,” read one direct column.

Within eight days of the train’s arrival, the virus killed its first victim at the Essondale Hospital on Coquitlam’s Riverview lands, according to research by local historian Niall Williams. Over the next two weeks, at least eight more would die of Spanish flu.

DEVASTATION

By mid-November, with the war over in Europe, the pandemic had already peaked across the Lower Mainland (though caseloads would surge again in February). At the hospital in Coquitlam, 33 soldiers and a Canadian army nursing sister had died.

It’s thought the influenza death rate hit 8.3 per 1,000 people that season in Vancouver, higher than many other major cities across Canada (though measurements vary) and several magnitudes greater than what the country as a whole is experiencing today with COVID-19.

In a series of oral histories recorded in Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood half a century later, survivors of the 1918-19 pandemic remember seeing “bodies piled high like cordwood,” waiting to be taken away by overwhelmed funeral parlours. Nora Hendrix, grandmother of legendary rock star Jimi Hendrix, said she remembers how “plenty of people was dying, dying like flies. Oh the big, healthy people was just dying like nobody’s business.”

Or as historian Mary-Ellen Kelm put it, “It was just devastating.”

The pandemic is not only remembered for how many it killed, but for how it killed.

Unlike COVID-19, which so far has disproportionately taken older people and those with weakened immune systems, Spanish flu seemed to kill the strongest, most fit in society. The highest mortality rates, said Kelm, were among those between 15 and 46 years old, as well as pregnant women and newborns.

“The Spanish flu affected those in the prime of life rather than old people. It’s the opposite of what we’re seeing now,” Kelm said.

The spread of the virus across the Tri-City civilian population remains unclear, though studies suggest immigrants and Indigenous peoples were among the hardest hit across B.C.

Today, the odd recorded death stands out among local labourers, like Soo Joe Shing Chow, a 42-year-old Coquitlam foreman who died at 麻豆传媒映画General Hospital three days after he was admitted, or Lawrence Wainwright, a first-generation Coquitlam shoe clerk whose parents had immigrated from Britain and who died before his 16th birthday.

Yet those with money and power were not spared: Matthew Marshall Jr., a 31-year-old alderman (the old term for a city councillor) and timber inspector who never went to war, had gained further notoriety as a soccer star on the Coquitlam’s 'Black and Tan' squad before he too was taken by the flu.

A LEGACY OF DEATH

Over 100 years later, Kelm, like all of us, sits at home under quarantine in the face of a new contagion, worrying about how an economy crashing to levels not seen since the Great Depression will impact families.

“The economic results of COVID-19 have shown the huge vulnerabilities of the gig economy… We know that people are teetering on the brink of poverty,” she said.

Still, when she looks back at what stands as the deadliest pandemic in the history of humanity, all the stories point to one sobering reminder.

“People don’t recall anything but disease and death when they look back at 1918,” said Kelm. “I don’t see any record of people saying we lost our jobs. Yes, people couldn’t get crops. Economic hardship was widespread.

“But people remembered the dead.”

*The illustrations in this story are part of the recently released graphic novel, . Drawing on Port Coquitlam's archival history, the story traces several turbulent years when devasting fire, flood and the flu rocked the residents of a town then advertised as the next Pittsburg. Now in the midst of our own pandemic, hundreds of copies of the story sit in boxes waiting for quarantine to be lifted.

Read more from the