The First World War gave us Remembrance Day. But long before anyone began observing two minutes of silent reflection, people were preserving the first photographic memories of modern conflict.

“It really was the first war of the camera,” said Don Bourdon, curator of images at the Royal B.C. Museum.

It was a conflict in which official photographers were attached to units, with cameras that could capture real action. Troops were photographed marching, moving and waving. The images made it into feature films. Pocket cameras carried by soldiers themselves furnished fascinating candid pictures of life on the front lines.

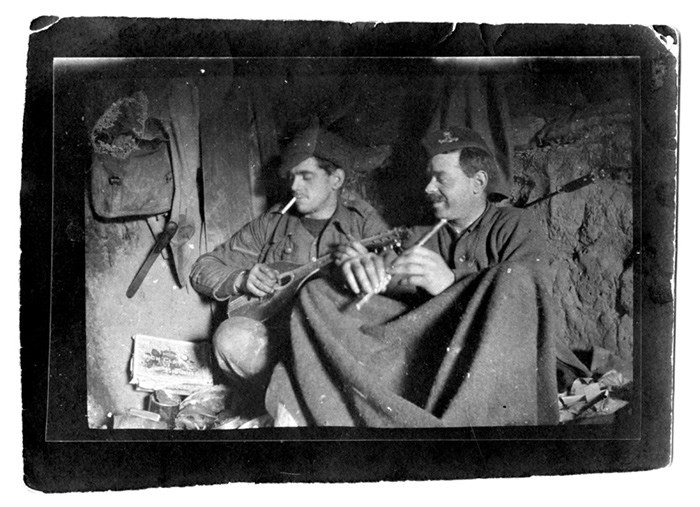

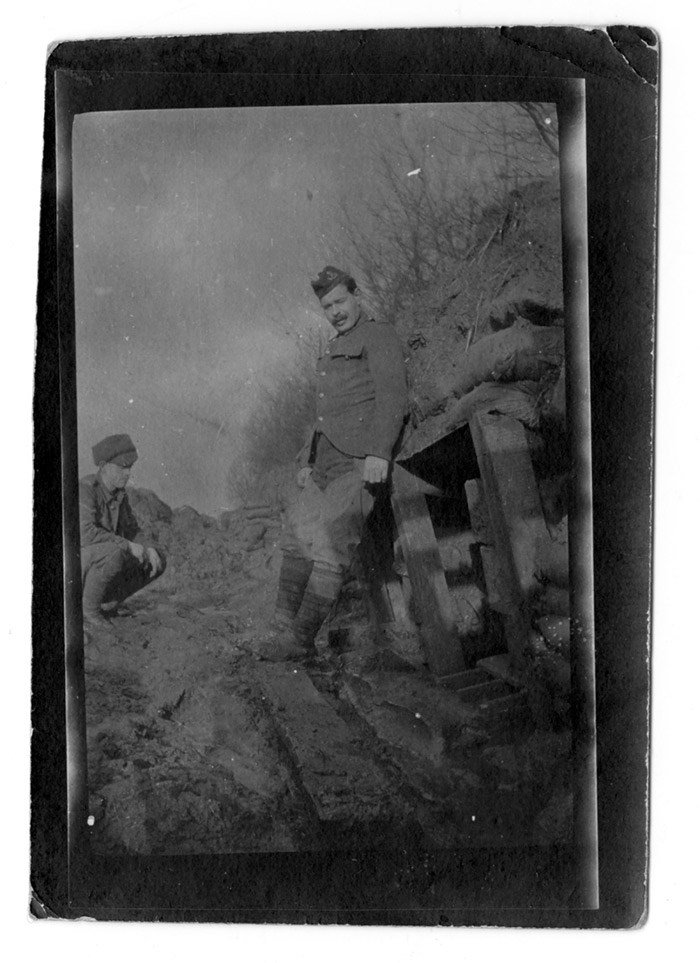

An image shot by a First World War soldier with a Kodak pocket camera shows members of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), which consisted of troops from Victoria, Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and Hamilton, Ont. Image G-06594, courtesy of the Royal B.C. Museum and Archives

An image shot by a First World War soldier with a Kodak pocket camera shows members of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), which consisted of troops from Victoria, Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and Hamilton, Ont. Image G-06594, courtesy of the Royal B.C. Museum and Archives

Jim Kempling, a historian at the University of Victoria and project manager of A City Goes to War, a digital platform for Canadian research into the 1914-1918 conflict, said the First World War was the first widely photographed war.

Earlier conflicts such as the American Civil War, 1861-1865, and the Boer War, 1899-1902, were photographed. But cameras were big and clumsy. Pictures were mostly staged portraits, and moving pictures had not been developed.

The First World War came to Victoria in a movie. Kempling said a British silent movie called The Battle of the Somme arrived in November 1916 and played to packed houses at the Variety Theatre for an entire week, with continuous showings from 1 to 11 p.m. “It was a smash hit,” he said.

While much of it was staged, he said, the film included live-action footage of troops in conflict, getting hit by artillery and “all that kind of stuff.”

Kempling said The Battle of the Somme movie scored a propaganda victory: It eventually made its way to the U.S., where it helped convince Americans to enter the war in time to get troops into battle by 1917.

An image shot by a First World War soldier with a Kodak pocket camera shows members of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), which consisted of troops from Victoria, Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and Hamilton, Ont. Image I-83669, courtesy of the Royal B.C. Museum and Archives

An image shot by a First World War soldier with a Kodak pocket camera shows members of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), which consisted of troops from Victoria, Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and Hamilton, Ont. Image I-83669, courtesy of the Royal B.C. Museum and Archives

He said that propaganda victory stands in contrast with the battle itself, now often regarded as a military disaster. On the first day alone, July 1, 1916, the British Army suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 killed, the worst day in British military history.

Official photographers and propagandists weren’t the only ones providing a visual record of the war. Museum curators and archivists are uncovering a photographic treasure chest of casual, candid moments captured on film by soldiers themselves.

Kodak first produced its Vest Pocket Camera in 1912. Only slighter bigger than a modern smartphone, it was a favourite of allied troops and quickly earned the title the “Soldier’s Camera.”

A book published this spring, The Vest Pocket Kodak and the First World War by Jon Cooksey, details the kind of revolutionary exposure the instrument gave to the conflict.

Bourdon said that carrying the camera was against regulations and could earn a soldier a court martial. Nevertheless, officers seemed to turn a blind eye — many even carried one themselves.

“There were people just snapping away and the fact they just ignored the prohibition is very interesting,” said Bourdon.

With a fast enough shutter speed to capture action without the distinctive blur found in so many previous photos, the little Vest Pocket Kodak camera provided a candid picture of life in the trenches: Soldiers mending their uniforms or picking lice, message-carrying pigeons just released from an official pigeon coop or a bayonet casually jabbed into a trench wall.

A Kodak autographic vest pocket camera could be folded into a compact case. Photograph By DARREN STONE, TIMES COLONIST

A Kodak autographic vest pocket camera could be folded into a compact case. Photograph By DARREN STONE, TIMES COLONIST

The Royal B.C. Museum has a handful of these pictures, Bourdon said, but so does virtually every other museum across Canada, as do many people in their attics or garages.

One of the things that interests Bourdon is the contrast between the casual nature of soldiers’ pictures and the buttoned-up tone of the official images.

Unlike the soldier’s snaps, the official photographs seemed to follow a kind of script. Soldiers are always in full kit, and no photos of dead soldiers — except for enemy dead — were ever distributed. Captured Germans were often shown smiling and carrying Allied wounded.

“It was all to show: ‘We are winning the war and look: These Germans are surrendering and are happy because otherwise they would get it from our bombs,’ ” he said.

Read more from the