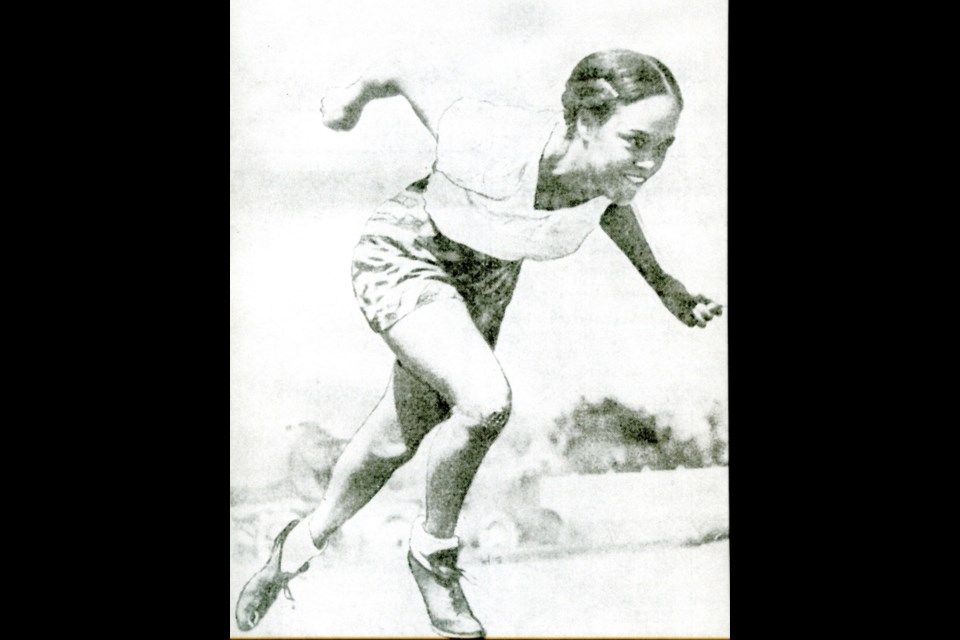

Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»sprinter Barbara Howard was the first black female athlete to represent Canada internationally in any sport. It happened at the 1938 British Empire Games in Sydney, Australia when she was still just a teenager.

At the time, Barbara had no idea she was making history. Mostly she felt disappointed with her performance. She advanced to the 100-yard final on the grass track of the Sydney Cricket Ground but finished sixth overall in the final in 11.6 seconds, half a second behind the winner, Decima Norman from Australia, who ran a Games record time. Sixth place in the British Empire was pretty good for a 17-year-old competing for her country abroad for the first time, but it wasn’t the gold medal Barbara had envisioned for herself.

“I was ashamed because I thought I was going to win,” Barbara lamented in a 2010 interview. “I didn’t do as well as I thought I could.”

Black female athletes rare in 1938 Australia

She felt she’d let down her country and those back home who raised money to cover her travel costs. Later in the Games though, Barbara helped Canadian relay teams to silver and bronze medals. And she did this while carrying a heavy burden that would have slowed down most young athletes no matter how talented.

“I’d never been away from home in my life before,” Barbara said. “I’d never been to Girl Guide camp or anything.”

The month-long voyage across the Pacific Ocean aboard the Aorangi liner disrupted her training. Then immersed in a completely new foreign land, Barbara battled homesickness. After appearing on the front pages of several Australian newspapers and becoming something of a local celebrity in Sydney, she also felt overwhelmed by the unfamiliar attention directed towards her. Black athletes, especially female, were a rarity at that time in Australia. Admirers showered her with gifts including one who gave her a plush koala bear. “I was spoiled,” she said in 2012.

She kept this koala as a souvenir for almost 80 years along with her kangaroo leather track spikes and BEG medals, now part of the BC Sports Hall of Fame collection.

Spent her childhood sprinting around Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»neighbourhoods

Barbara first discovered she could run like lightning while a student at Laura Secord Elementary School in Vancouver. When she heard the morning school bell ringing, she could sprint the block-and-a-half from her family’s house at 10th and Nanaimo and be sitting comfortably at her desk in time for class to begin. By the time she attended Britannia High School, she was known as one of the city’s fastest sprinters. She often trained on the grass infield of Hastings Park, dodging the droppings of the racehorses.

To earn selection to the Canadian BEG team, Barbara scampered 100 yards in 11.2 seconds at the Western Canada British Empire Games trials at Hastings, one-tenth of a second faster than the existing Games record. She beat established Canadian international sprinters Lillian Palmer and Mary Frizzell (both also from Vancouver), who had helped Canada’s 4x100m relay team to a silver medal at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, in the process becoming the first-ever female Olympic medalists from British Columbia.

“Of course, they were all ready to go but guess who won?!” she said with a chuckle. “They probably had their bags packed!”

World War II changed course of Barbara's sprinting career

In almost any other era, Barbara would have used her experience at the 1938 British Empire Games as a stepping stone to further forays in international competition, the next being the 1940 Olympics in Tokyo. However, timing worked against her. World War II broke out in 1939 and the next two Olympics as well as most international competitions worldwide were cancelled. By the time the Olympics resumed in 1948, Barbara’s sprinting career was over. She had retired from athletics years earlier and was already well into her teaching career. She taught at several Vancouver-area elementary schools over 43 years after becoming the first member of a visible minority hired by the Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»School Board in 1941.

Barbara’s family had deep roots in Vancouver, predating the city’s incorporation. She liked to share the story of how her grandfather had owned one of Vancouver’s earliest barbershops, the Abbott Street Shaving Parlour and Baths, and when the Great Fire of 1886 engulfed the fledgling city, he outsprinted the flames to the safety of Burrard Inlet while carrying his barber’s chair on his back.

Recognition for Barbara’s trailblazing track career took decades to arrive. Canadian sports historian Ann Hall was likely the first to identify Barbara’s place among Canadian athletes in her 2002 book The Girl and the Game. After receiving the Remarkable Woman Award from the Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Park Board in 2010, induction into the Burnaby Sports Hall of Fame (2011), the BC Sports Hall of Fame (2012), and Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame (2015) followed.

A year after her death at the age of 96 in 2017, the City of Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»renamed a park near the Cambie Street Bridge as Barbara Howard Plaza in her honour. For many years now, tens of thousands of runners have jogged by this spot along the Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Sun Run race route. One of Vancouver’s great pioneer athletes who first learned she could run like the wind on Vancouver’s streets would have no doubt been delighted by that fact.

The celebrates over 150 years of sporting achievement in British Columbia, inspiring future generations through its collection of 28,000+ artifacts. With exhibits honouring legendary athletes, teams, and sports organizations, we highlight the history of sports in B.C. and the individuals who’ve shaped its rich sports culture.

Explore B.C.’s sports legacy — !