Mammoths lived on the land that is now Greater Victoria and all the way up Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Island, and thrived in a landscape of grasses, spruce and pine trees and other plant life, according to the author of new research into the prehistoric elephants.

A study from Simon Fraser University said the giant mammals — ice-age cousins of the modern elephant — roamed here 23,000 years ago and possibly longer than 45,000 years ago, thousands of years earlier than scientists had originally believed.

Adult woolly mammoths stood up to 3.7 metres tall and weighed up to 7,300 kilograms. They ranged from the B.C. Interior to the San Juan Islands and western Washington state, where remains have been found.

Laura Termes, a Qualicum Beach native, conducted the research at SFU and published the findings in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. She said the study examined 32 suspected mammoth samples collected on Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Island.

None of the Island fossils came from intact, fully articulated skeletons. Rather the pieces of bone, tusks and teeth were collected at beaches, construction sites and aggregate mines from Victoria to Cumberland and Courtenay.

Termes said of the 32 samples, 16 were suitable for radiocarbon dating.

The youngest sample was found to be around 23,000 years old and the oldest turned out to be beyond the range radiocarbon dating could measure, meaning it was older than 45,000 years.

“A lot of the [remains] were found in aggregate pits and beaches around Victoria and a lot of other places on the Island, and there are probably a lot in private collections, which is very exciting,” Termes, a PhD candidate in SFU’s department of archeology, said in an interview.

She said the study showed that mammoths lived on Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Island for a long time, much longer than originally thought.

Termes said she was initially expecting similar results to the two samples previously dated, but found mammoths that were much older than 23,000 years.

“It is fantastic that they could be preserved for that long.”

Termes said having the support of the Royal B.C. Museum and the Courtenay and District Museum and Palaeontology Centre, which both allowed access to their collections, was invaluable to the study.

The University of British Columbia’s Ancient DNA and Protein Research facility confirmed that the fossil samples were mammoths and not those of whales or other ancient animals, Termes said.

She said the samples of mammoths showed they thrived here between “environmental episodes” of colder temperatures and glacier sheets. As temperatures grew colder, plants changed to mosses, likely causing the mammoths to move on, possibly south. “They could have died in Victoria, trapped, or squeezed out,” she said. “The sea levels were low enough that they moved on. It’s not known,” she said.

Termes is expanding her study into the Interior.

It isn’t clear how large the population of woolly mammoths was on the Island. They were large and dominant, she said, and existed with other mammals like the short-faced bear and ancient bison.

“Mammoths were ecosystem engineers. Their body size was enormous and they could trample saplings to allow grasslands to expand and to support more plants and vegetation. Their big poops would also give more nitrogen to the soil and maintain food supplies.”

In late 2022, workers excavating a site for a long-term-care home in Saanich unearthed ancient bison bones dating back at least 12,000 years.

Pieces of horn, skull, backbone, shoulder, rib cage and feet were found, and are now stored at the Royal B.C. Museum.

Termes said archaeologists need all the help they can get because while mammoths were enormous, finding intact samples in British Columbia is quite rare. And in places like aggregate mines and construction sites, it’s like “looking for a needle in a haystack.”

She said unlike in the arctic regions, where preserved mammoths have been found, in southern B.C. that just does not happen. “Instead, we may get an isolated molar that’s been tumbled around in the water for a long time, or maybe a piece of a tusk. And these are what everyday people are encountering,” she said.

“So maybe it’s a dog owner, taking their puppy for a walk on a rainy day, or a gravel pit operator at work. I really like how these magnificent animals are finding their way into people’s lives in routine and everyday ways.”

Victoria Arbour, curator of paleontology at the Royal B.C. Museum, said the research highlights the important role of museum collections for understanding how life has evolved and changed in British Columbia’s deep history.

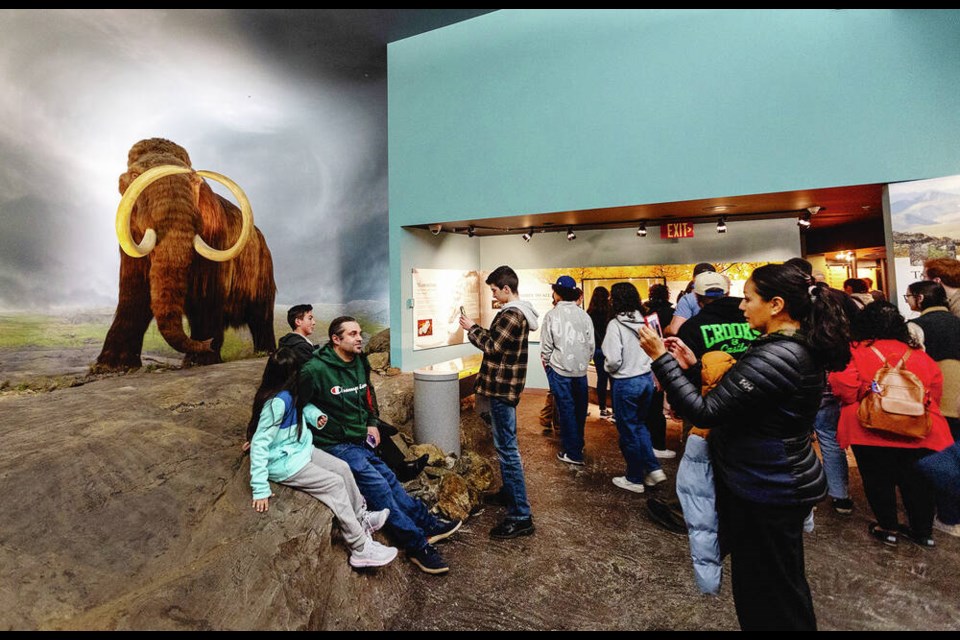

“It’s great to see Woolly’s relatives in the Royal B,C, Museum’s collections in the spotlight through this research study,” said Arbour, referring to the famous mammoth display at the museum.

Termes said her study is part of a larger look at megafauna in B.C. and she plans on radiocarbon dating mammoth samples from other parts of the province.

The Courtenay and District Museum and Paleontology Centre has one of the Island’s most treasured mammoth relics. A mammoth’s molar was discovered on the Brown’s River in 1928 and has been radiocarbon dated to about 29,000 years ago.

This molar is considered unique in being the most northerly mammoth tooth found on Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Island. It’s on display on the main floor of the museum.

The mammoth study is part of SFU’s B.C. Megafauna Project looking at ice-age animals found in British Columbia. The aim is to find and document as many of the ancient animals as possible, from both public and private collections. “We want to know when they lived [from radiocarbon dating], information on their health and age [from the bones], and also information on their diet and how and where they moved across ice-age British Columbia [using chemical analysis],” the project says.

Wondering if you have a piece of an ice-aged animal? Contact the project and scientists will help identify it. Go online to: sfu.ca/megafauna.html