A British Columbia public health order requiring residents to show proof of vaccination is raising “grave concerns” it will further exclude several already marginalized populations.

That’s according to 25 organizations that advocate for everything from civil liberties to just treatment for drug users, undocumented and disabled British Columbians.

In a published Sept. 1 and addressed to Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry and Health Minister Adrian Dix, the groups claim the vaccine passport system will shut out thousands of already vaccinated people from public life because they don't have proper identification, access to a smartphone or legal immigration status.

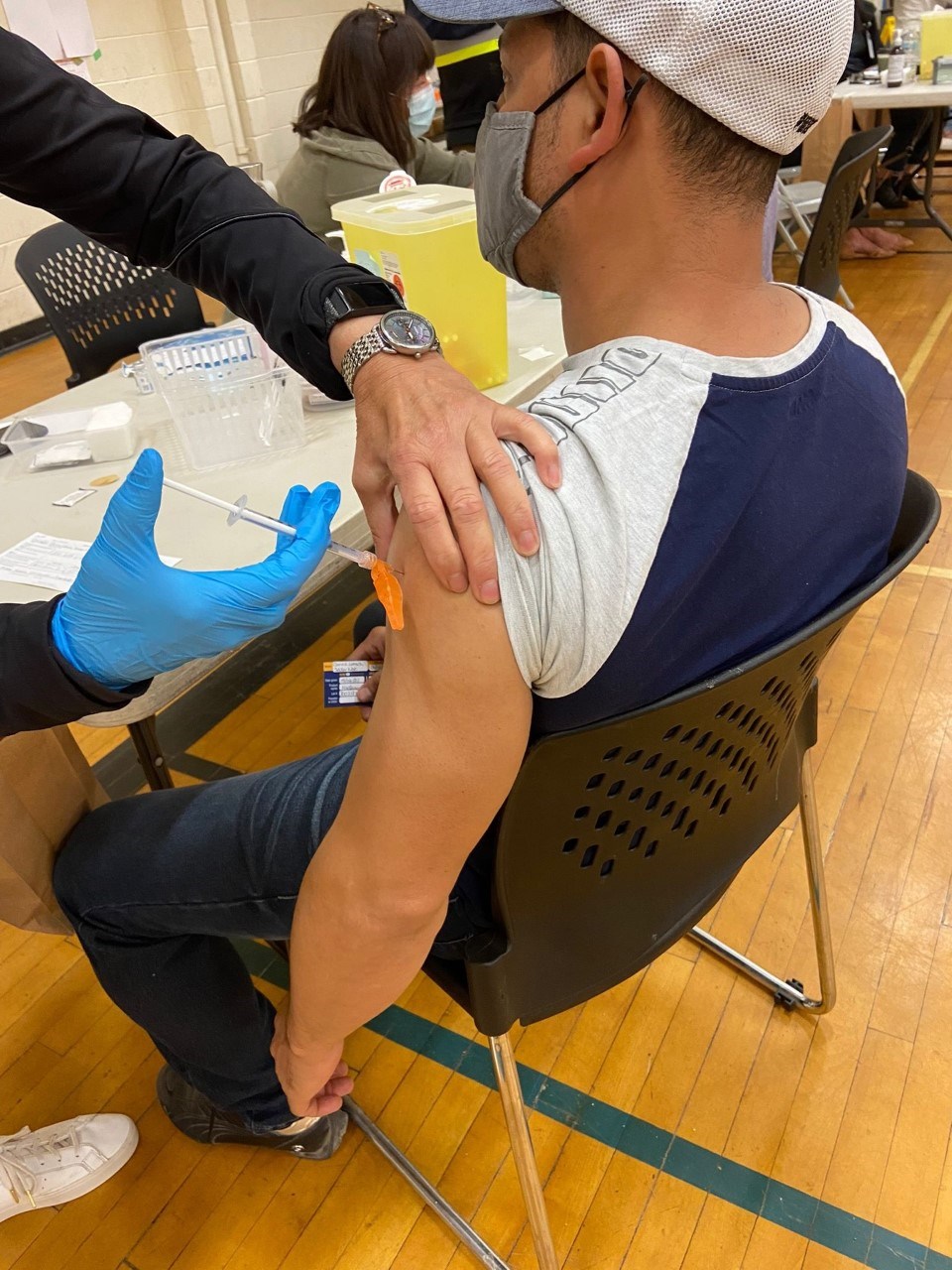

“We’ve had more than 2,000 people come to our vaccination clinics,” says Ingrid Mendez, executive director of Watari Counselling and Support Services Society, a community group that works with migrant workers and other marginalized people.

“Many of them are coming to us: ‘What am I going to do. How am I going to access this vaccine card?’ People are getting stressed because of this.”

Last week, the B.C. government announced it would be launching a vaccine passport system that would bar unvaccinated British Columbians entrance to everything from movie theatres, concerts and sporting events to gyms and restaurants.

Anyone entering such venues will be required to show proof they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine by Sept. 13 and full vaccination status by Oct. 24.

In an email to Glacier Media, a Ministry of Health spokesperson said the B.C. government would share details on how people can access documentation ahead of the Sept. 13 deadline.

“The province is working to ensure vulnerable populations, like people experiencing homelessness or those who may struggle to access computers, have options when it comes to accessing their proof of vaccination,” wrote the spokesperson.

VACCINATED THREATENED WITH FURTHER ISOLATION

The "proof of vaccination" plan, rolled out to protect people from a rising number of cases, appears to be driving the unvaccinated to clinics.

Mendez says that goes for undocumented people across Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»as well. But unlike many British Columbians, Mendez says there are upwards of 10,000 people in the Metro area whose immigration status prevents them from proving they’ve been jabbed.

For Adriana, a 36-year-old mother of two in Vancouver, the prospect of not entering businesses or community centres threatens to throw her life back into seclusion. Adriana says she fled to Canada from Mexico four years ago after someone tried to kill her and her husband (Glacier Media has not published the woman's last name for fear of deportation).

Since arriving in Canada, the husband has worked in construction, earning enough money for the family to get by. But without immigration status, they don't have access to medical insurance and every trip to the doctor threatens to cost a fortune.

During the pandemic, Adriana says she's spent most days alone with her children, isolated from friends and her family back in Mexico. So when Watari offered to get the couple vaccinated, they jumped at the chance.

Since receiving their second dose in July, life has opened up once again — that is, until she learned there would be a proof-of-vaccination requirement for people like her.

"We won’t be able to enter a community centre, enter a restaurant," she says. "I’m frustrated. I’m worried they are going to ask my husband for proof at work."

It's people like Adriana the letter points to when it claims sweeping vaccine passport policies, however well-intentioned, “can have the effect of forcing people into isolation, cutting off their lines of resources, and making their lives even more dangerous during a pandemic.”

What is she supposed to tell her 10-year-old who regularly goes swimming and plays soccer at a local community centre, asks Adriana.

"How can I explain to my kids we can’t enter when we are both vaccinated? I didn't realize what was going to happen."

Then there are the over 9,000 temporary foreign agricultural workers in the province, many of whom have trouble accessing a Medical Services Plan (MSP), the gateway to accessing a digital or paper proof of vaccination.

“Agricultural migrant workers who come here and grow the food we eat. Many are not enrolled with MSP,” says Mendez. “Many don’t have a phone that will deal with an app.”

Watari has an office in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where a high proportion of people live without proper housing. There, Mendez and her team offer counselling, run a youth outreach program and cook food for people on the street and in Single Occupancy Resident (SRO) hotels.

Like agricultural workers, Mendez says many of the Canadian citizens she comes into contact with also don’t have access to a smartphone to download the Ministry of Health app so they can prove they have been vaccinated.

As the letter to Henry and Dix notes: “The PHO’s order directs people to register online at the B.C. vaccine card website, and references a secure paper version, but has not included any additional support for registering people without required identification, or those without regular internet access.”

PROPOSED FIXES

The 25 organizations are calling on the B.C. government to close several gaps before the vaccine passport program comes into effect Sept. 13.

That would mean stepping up supports to help register low-income people without a government ID as well as drug users who rely on access to community support services but could be barred from them under the new system.

The group says the province should find another option for undocumented migrants and those without identification, so they can prove their vaccination status without a personal health number or government identification like a driver’s licence or a B.C. services card.

Anyone who can’t get vaccinated due to a pre-existing medical condition should be offered alternatives as well, the group says, such as exemptions or even hospital-based vaccinations to ensure they can get proper treatment if there are unforeseen side effects.

Mendez says that with 10 days to go before the Sept. 13 deadline, concern is building.

“We’re marginalizing people even more,” she says. “We need to find another way to do this.”