A shot from a rifle. A trap. Poison. For decades, a grizzly bear’s encounter with a humanity’s footprint often meant death as settlers spread across North America.

Grizzly range across the continent sits at less than half what it once used to be. And while conservation efforts have helped buoy some grizzly populations over the last several decades, some places remain more deadly than others.

Over the last seven years, young grizzlies in British Columbia’s Elk Valley have faced the lowest survival rate recorded in North America, according to a published in the journal Conservation Science and Practice.

Lead author Clayton Lamb, a wildlife scientist with and researcher at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, said roughly half of the young male grizzlies in the area were dying every year — a combination of human conflict and collisions with a train, truck or car.

“These bears are dying at extraordinary high rates,” said Lamb. “For any one year it's like a coin flip if you're gonna live.”

Elk Valley grizzlies were involved in a third of all road collisions in the province despite only making up 0.6 per cent of the province’s grizzly population. And when it comes to rail collisions, nearly half the recorded mortalities occur in the Elk Valley, the study found.

As a result, the researchers estimated government mortality databases are underreporting grizzly deaths by 65 per cent — meaning that for every dead grizzly, two go uncounted.

A ripple effect

The high death rate for young grizzlies has meant habitat in the Elk Valley is regularly opened up for more young bears to move in. Grizzlies from as far away as and Glacier National Park in the U.S. find a valley rich in both food and humans.

Known for massive coal mines, the Elk Valley is laced with busy highways and rail connections that weave through towns as they link Canadian provinces east of the Rockies with ports on the coast.

It’s here where Lamb and his team of biologists — one from the provincial government, others from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature based in Kaslo, B.C. — set out to understand why grizzlies were dying at such high rates and what was keeping the their population afloat.

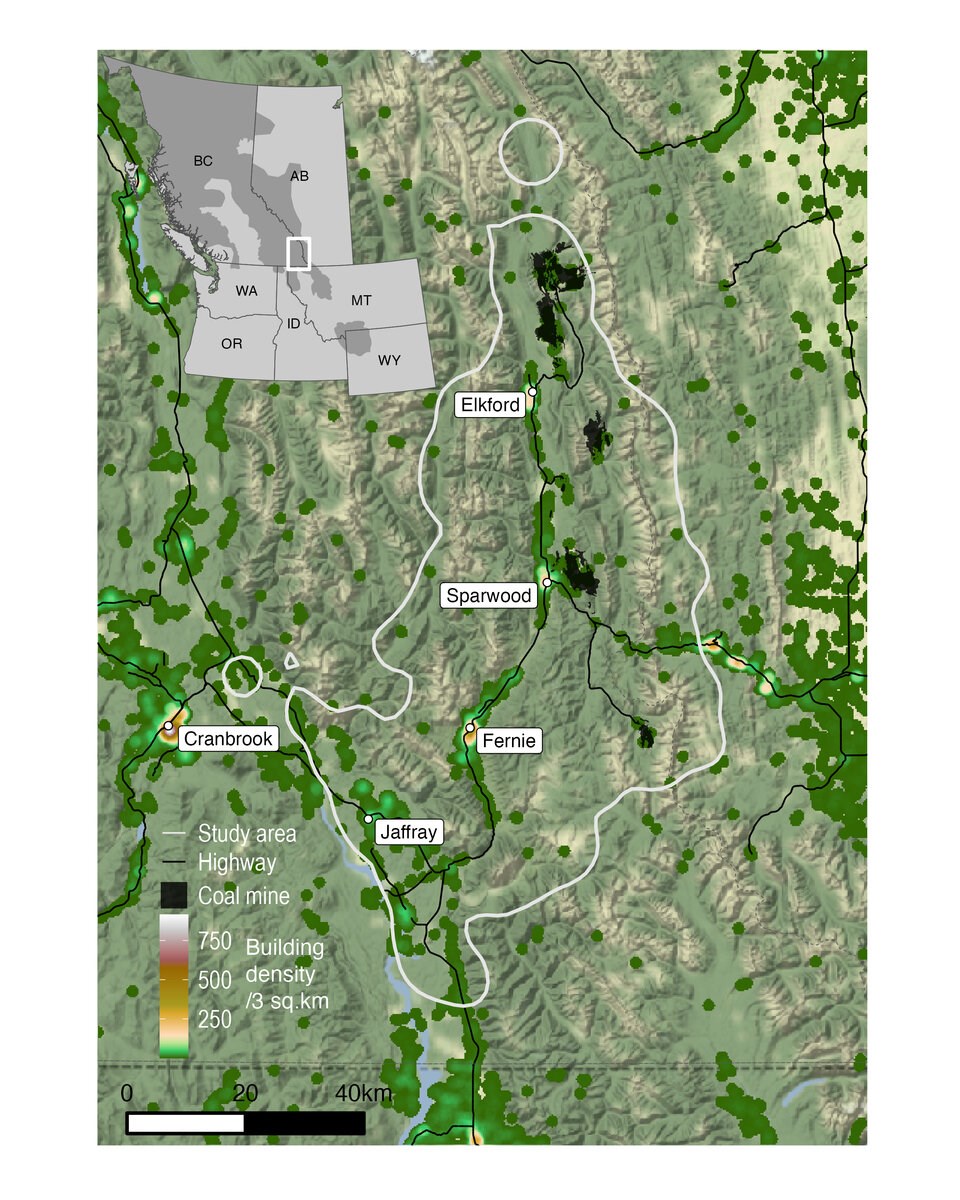

To find out, the research team captured 76 grizzly bears between 2016 and 2022, monitoring their behaviour, reproduction and survival using radio collars. While the bears roamed an area stretching seven kilometres into Alberta, most of their territory occupied a swath of the Rocky Mountains east of Cranbrook that contains five large open pit coal mines, and the towns of Elkwood, Sparwood and Fernie. The region is also an active recreational area, popular among off-road vehicles users, hunters, fishers and mountain bikers.

Over seven years, they tracked 14 grizzly bear deaths — six due to human-wildlife conflict, six involved in collisions with a vehicle or train, one which died of natural causes, and another whose death was suspected to be connected to a human.

Lamb recalls the gruesome task of tracking down the young grizzlies after their radio collars stopped moving.

“They'd be hit, and then they could make it a few hundred metres and I would find them dead,” said Lamb. “You know that the driver obviously knew they hit something but that as soon as that bear gets off the highway, it essentially doesn't exist from a data perspective. The province doesn't know about it. It just dies in the bush and nobody knows.”

Local bear population overwhelmed by high death rate

Whether in a rail or road collision, Lamb estimates as few as one in five dead bears gets recorded. For a population of roughly 100 grizzly bears, Lamb says it’s generally accepted that a mortality rate of roughly five per cent, or five bears, is sustainable.

Road and rail deaths alone pushes the death rate to six per cent. Then there are deaths due to conflict with humans, which regularly doubles that death rate, meaning that without in-migration, seven more bears are dying every year than the population can sustain.

Grizzlies from elsewhere have moved in, filling the habitat left empty by those dead bears. But a population that relies on migration raises serious questions over its long-term survival.

“We're always wondering, how sustainable is this on our end?” Lamb said. “For example, if some of the wilder areas around the valley, if they all of a sudden get developed and we build a coal mine there or we build new towns in these places, and we kind of reduce the pool that we're pulling dispersers in from — maybe this currently sustainable dynamic, maybe it all collapses.”

Relying on migration to replace a fast-dying bear population could be a problem beyond B.C.’s grizzly dense Elk Valley. The more Lamb and his colleagues count dead grizzlies in somebody’s front yard or on the side of the road, the higher chance their deaths could lead to a “ripple effect” that impacts the demographics of bears up to 100 kilometres away in places we think of as protected national parks.

As Lamb put it: “It’s just this wicked spiral that we're in.”

Coexistence still a long way off

In recent decades, a move to protect grizzly populations has often focused on reducing human-bear conflicts, either by locking away attractants or reducing the number of bears killed by hunters.

From Yellowstone to the southern Canadian Rockies, conservation programs have allowed grizzlies to reclaim some of their lost historic range, which today sits at 55 per cent of its historic total.

But even as grizzly populations rebound, humans have continued to expand their settlements, setting up a test as to whether people and bears can coexist.

​For Lamb, Elk Valley might be the deadliest place for grizzlies in B.C. But that fact also makes it an easy candidate for conservation. By focusing attention and dollars in one small area of the province, he says governments and locals could remove between a third and half of all grizzly road and rail collisions in all of B.C.

“There's a lot of bang for their buck investing in conservation solutions here,” Lamb said.

Despite at least 40 years of progress in advancing the protection of B.C.’s grizzly populations, Lamb says many communities have yet to switch to a “coexistence mindset” fast enough and are still not set up to live alongside large carnivores.

More support needed for electric fencing, fruit tree removal

Part of the gap is financial. Unlike Alberta or Montana, the B.C. government doesn’t have dedicated coexistence programs to reduce the availability of attractants, namely garbage, livestock and fruit trees.

Lamb said B.C. lacks a cost-sharing program that helps ranchers with electric fencing. Other residents, he said, may be convinced to remove a fruit tree in their backyard if there was better financial support.

Glacier Media reached out repeatedly to multiple ministries for comment but had not heard back more than 48 hours past its initial deadline.

When it comes to roadway deaths, Lamb says there’s already a project that aims to set up electric fencing — a proven deterrent for grizzlies — along 27 of the valley’s 100 kilometres of highway.

The project, which is not finished and not fully funded, includes dedicated wildlife road crossings in what Lamb describes as a “positive” move forward.

“Railway collisions? Almost no progress,” he said of negotiations with CP Rail, which recently rebranded as CPKC after buying out Kansas City Southern Railway in 2021.

“We really struggle working with the rail company.”

CPKC spokesperson Terry Cunha said the company has engaged with the Canadian government and “other institutions concerning rail-related wildlife strikes.”

“Actions we have taken include focusing efforts on vegetation management along the tracks in key areas through the mountains to reduce wildlife activity close to the railway, support wildlife sightlines and ensure room for animals to safely exit the tracks,” Cunha said in an email.

“Bear-train collisions pose a complex problem, with no simple solution.”