Replacing single-crop farming with a diversity of plants, animals and farming techniques will maintain food production while increasing farmers’ income and reducing negative impacts on the environment and climate, a new global study has found.

For over a century, modern agriculture has been increasingly characterized by intensive farming systems that use large volumes of chemicals and simplified crops to yield the most food. But the so-called ‘Green Revolution’ has had its costs: an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss and an often unsustainable use of water, according to the published in the journal Science Thursday.

Claire Kremen, the study’s senior author and a researcher from UBC’s Biodiversity Research Centre, said the findings offer a evidence of a new path for food production at a critical time.

Agriculture “isn't really serving humanity — both from the environmental side and also the social side,” said Kremen.

“We have a lot of people who are now suffering from obesity, and another still large component who doesn't get the nutrition they need.”

Evidence from 2,655 farms shows diverse farming works

In the largest study of its kind, Kremen and more than other 50 researchers from around the world combined data from 24 studies across 11 countries — ultimately examining the diverse practices of 2,655 farms across Africa, Asia, the Americas and Europe to understand how different styles of farming impacted the environment, human health and income.

Some of the farms were large single-crop palm oil plantations in Indonesia. Others, in places like Brazil, rolled out some combination of mixing mammal livestock with birds, bees and fish; rotating crops throughout the year; conserving soil through the application of natural fertilizers like compost; conserving water; and planting non-crops like hedgerows to protect crops from wind, or strips of flowers to attract wild pollinators.

Diversifying livestock and conserving soil were the two strategies that led to the most consistent benefits for people and nature. But the study’s most novel finding showed that there was no silver bullet that worked on every farm. Instead, combining farming strategies most often led to “overwhelmingly strong benefits” — especially for wildlife and food security.

“Conversely, many national strategies and programs focusing on agricultural intensification did not achieve win-wins,” the authors wrote.

Diverse farming helps farmers through extreme weather, benefits wildlife

Zia Mehrabi, a former UBC post-doctoral researcher and now a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in Malawi, the government has pushed to intensify mono-crop maize production in recent years.

But those practices opened up vulnerabilities, while farmers growing a mix of crops tended to have better nutrition and fared much better through extreme weather events, the researchers found.

“The push toward monoculture has had a negative effect under drought. They can lose out completely with these climate shocks,” said Mehrabi.

​In North America, where industrial agricultural came to dominate production in the 20th century, Mehrabi said concentrated farm production has led to environmental disaster in many places.

“What we’ve seen is a massive collapse of biodiversity in our farmed landscapes,” he said, pointing to the over application of fertilizer and decimation of natural habitats.

While far from the continent's heart of agricultural production, Kremen said the consequences of oversimplifying farming can be seen locally on British Columbia’s blueberry farms.

“They pretty much grow from one side of the field to the other. It's all blueberry. There's very little of any other kind of habitat or any kind of diversification practices being used in that system,” said Kremen. “And since that has happened, increasingly, there's a pest issue that has emerged.”

“If we use more diversification practices, we probably wouldn't have the pest issue that we have. We wouldn't need to use such extensive pesticides that ultimately has negative consequences for human health and for wildlife.” ​

A race to rejig the farm

Amid calls to cut meat from human diets in order to improve health and the environment, the latest study shows farm animals play an important role if properly incorporated into a complex farm system.

“People just need to eat less of them. And we need to redistribute livestock,” Mehrabi said. “We essentially have a load of cows creating manure in one part of the country, and then farmers producing all the crops they eat in another part of the country. It makes no sense.”

The study said economically advantaged nations need to reverse course on such practices to “recover from environmental and social damage already done” while developing countries need to minimize the impacts from simplified agriculture before it expands.

On its current trajectory, the mechanization of agriculture is expected to begin taking over much of Asia by mid-century, and Africa by the 2070s, said Mehrabi. The process is largely driven by people moving to cities — without labour on farms, many turn to machines.

But Mehrabi said that process doesn’t have to lead to big mono-crop farms like those that have expanded over the U.S., Canada and Europe. Instead, Mehrabi said what he and his colleagues found should push people to look for hi-tech solutions that make old ways of farming more effective.

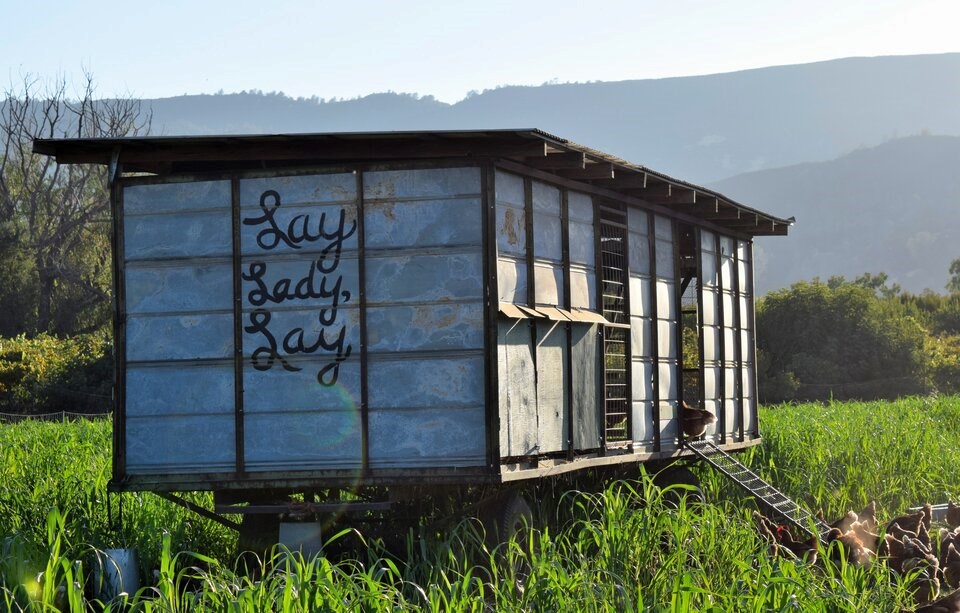

Allowing chickens to churn pasture for cows, while growing animal feed next door to vegetables is not a new idea. But amid a push to industrialize agriculture, diversified agriculture gained traction among a small but growing group of farmers after it was popularized by books like Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

What Kremen, Mehrabi and their more than 50 other colleagues have done is build a global body of evidence showing those once fringe ideas work for both nature and people.

“A few decades ago, it was a few people on the fringe saying this was a good idea,” Mehrabi said. “Now, we have evidence from real agriculture systems that it works. It’s a strong mountain of evidence.”

“It should inspire, give a vision of what the future of agriculture could be.”

Transition to new agricultural system needs new incentives, funding

Taking a new agricultural path is especially important now, the study warns, in a world where many farmers are “working against the odds” — against high land rents, short-term leases, stringent food safety regulations, supply chain pressures and trade agreements that often favour corporate concentration in the agriculture and food sector.

Kremen said the study is not calling for a breakup of large farms, but rather finding the right incentives to make farming better for people and the environment.

“Farmers that have large properties could adopt these practices,” she said. “It might be a tall order to do it all at once, but they could definitely do this in a phased in kind of way.”

Farmers looking to make a switch from industrial to diversified agriculture face some of the biggest hurdles early on in the transition, according to Kremen.

In some cases, government incentives for certain water-thirsty crops might push farmers to over exploit water sources. Another challenge, Kremen said, is most seeds currently available to farmers have been bred for single-crop farming systems.

Then there’s moving from supplying a global supply chain to growing crops for more local markets — not an easy or cheap task when profit margins are slim.

“We're not suggesting that it's backwards looking,” said Kremen. “It's like, take the best of what people were doing for many, many centuries, and bring it together with newer methodologies to make this really work.”