Tareef Dedhar is spending the next few weeks lying in a bed on the first floor of his grandmother’s Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»home. The 25-year-old Squamish resident isn’t able to walk while he recovers from an open tibia fracture, a broken pelvis, a shattered ankle and a couple of broken ribs, plus some nerve damage to his left wrist.

He’s lucky.

“All things considered, it could have been much worse,” Dedhar said.

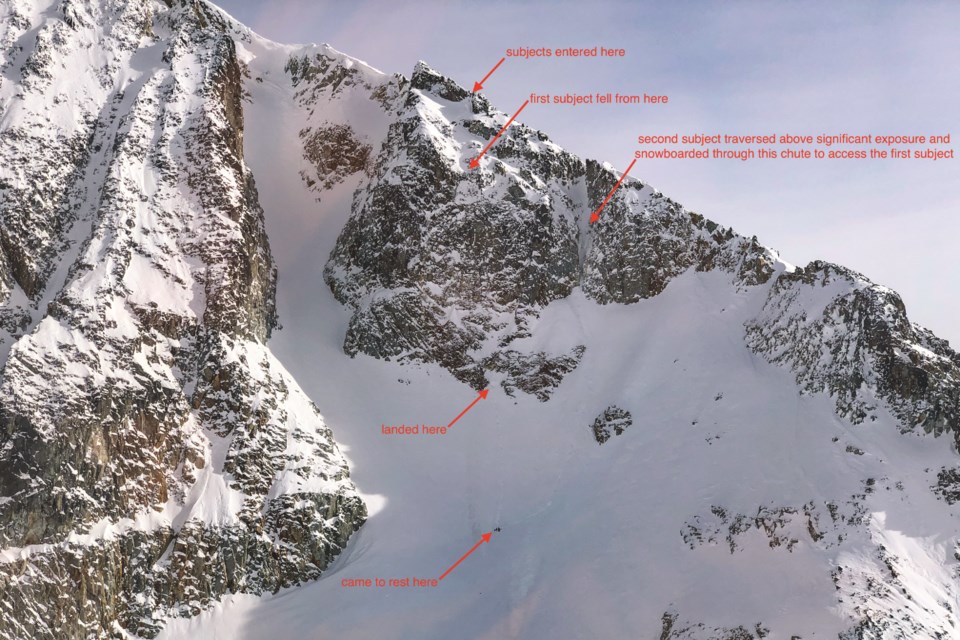

Dedhar suffered that laundry list of injuries falling off a cliff face on Wedge Mountain, in the Whistler backcountry, on March 17. According to his tracking watch, Dedhar fell about 150 metres, or nearly 500 feet, reaching a top speed of about 80 kilometres per hour. That’s roughly the equivalent of falling off a 45-storey building. Doctors estimate it will take between nine months and a year to regain most of his functionality.

The skier found himself above the rock face, attempting to navigate his way into the Northwest Couloir after realizing he and his touring partner, Charles-Antoine Leblanc, had missed the corniced entrance to their intended line. They had travelled too low on the ridge while following a digital map on their way down from the summit.

Tired after a few minutes of retracing their steps uphill and still far from the top of the couloir, the pair spotted what they observed to be a potential entrance to the slope. They knew the sheer terrain to skier’s left of the couloir was “unskiable,” said Dedhar, but after looking at maps, were satisfied a hard traverse right over a couple of small ridges would lead into the couloir and save them the uphill travel.

“I kind of wanted to go back up, but he was pretty confident that he could traverse there,” Leblanc recalled. “But I said, ‘I’m not going to go first.’”

That confidence was misplaced. Sitting on a ledge, Dedhar clipped into his skis and dropped in. The shallow, sugary snow gave way instantly, taking Dedhar with it.

“I was fearing the worst, that he was dead, because I couldn’t see what was after the last point where I saw him,” Leblanc said. “I thought it was probably a cliff, but I didn’t know how big it was.”

Dedhar tumbled along the slope for a few seconds before realizing he was airborne. “I thought it was over,” he said. “After what felt like a second or two, I saw that little snow patch where I ended up landing [and thought], ‘If I land there, there’s a chance.’ I was lucky enough to get that chance and land in that snow, and I managed to escape with my life and most of my body.”

Dedhar wrote about the experience ing, Tareef’s Mountain Misadventures, earlier this month—a practice the self-described “peakbagger” has kept up during his first full winter of ski touring. “For me, my trips are never fully complete until I do that,” he said. “The process of writing about that … is something I enjoy, and in this case, it was definitely a good way to process the entirety of the events.”

What went wrong?

Leblanc and Dedhar had climbed to Wedgemount Lake the night before. They slept for a few hours in the emergency hut, with a plan to set off early enough to avoid skiing sun-baked slopes later in the day.

(B.C.'s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, which encompasses BC Parks, confirmed the Wedgemount Lake hut is for emergency use only. "It is not to be utilized as a first come, first serve accommodation as it must remain available for emergency situations at all times," the ministry explained in a statement provided to Pique on April 28. A spokesperson for the ministry confirmed signage at the hut indicating that restricted use had been vandalized recently, and will be replaced by the park ranger during their next patrol. "All public visitors are asked to abide by the use restriction so that the hut can remain open and available for emergency situations," the statement concluded.)

It was the pair’s second venture into the backcountry together after meeting through the South Coast Touring Facebook group. The week prior, they had climbed Mount Matier, in the Duffey Lake area, in less-than-ideal visibility.

Leblanc, a splitboarder, was new to the Sea to Sky—and relatively new to the backcountry—after moving to the corridor from the Yukon late last year. He was looking for crews to tour with. “I saw how he was [on Matier] and I kind of wanted to do something bigger with him," said Leblanc, because he perceived Dedhar's mountaineering experience to be "pretty good." Leblanc suggested Wedge, an iconic but high-consequence, experts-only ski mountaineering route in Garibaldi Provincial Park. "He accepted," said Leblanc.

This time, it was a bluebird day with temperatures in the valley forecast to approach double digits. They made it to the summit shortly after 11 a.m. without issue. Just a few hours later, Dedhar was propped up on the steep slope, broken but unsure of the extent of his injuries and hyperventilating from the cold, while he and Leblanc—who just as miraculously made it to his touring partner in one piece after cutting left and scraping his way over the highly-exposed cliff band and slipping down a narrow chute—waited the more than three hours for a search-and-rescue (SAR) helicopter to show up.

SAR volunteers managed to extricate Dedhar with a longline, flying him to the Whistler Health Care Centre before returning to collect Leblanc. The following day, Leblanc skinned up to Wedgemount Lake to collect the overnight gear they’d left at the hut, while Dedhar laid on an operating table at Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»General Hospital.

The gradient maps gave Leblanc an idea of the level of exposure at hand, “but looking back at the slope from the helicopter, I probably wouldn’t have guessed it was that big,” he said.

So, where did it all go wrong?

It’s a question both men have asked themselves since Dedhar rolled to a stop after his long fall.

Dedhar cited “a bunch of different factors” leading to the unfortunate outcome, in his view, from failing to probe the snow he was dropping into, to not even considering the less-taxing option to skin up to the couloir instead of bootpacking. A major takeaway, said Dedhar, is the importance of “asking yourself why you’re making the decision or the evaluation that you’re making,” he explained. “If I’m sitting there, putting my skis on, feeling that snow, and I say, ‘That seems fine,’ why? Why does it seem fine? … Not just waiting for someone else to second-guess your decisions, but second-guessing your own decisions.”

For Leblanc, the incident served as a lesson to listen to his intuition in the mountains.

Dedhar acknowledged his quick “ramp up to the objectives” he’s tackled since first venturing into the backcountry on skis, despite a lack of more experienced mentors to tackle those objectives with.

But, asked if they would still consider that day’s objective comfortably within their skill set with the benefit of hindsight, both Dedhar and Leblanc maintained they would.

“I was quite comfortable the whole way [up],” Dedhar claimed. “On the way down, clearly, it didn’t go as planned, but the things that led up to what happened are definitely mitigatable.”

While Leblanc clocked a few more backcountry trips in the days and weeks after Wedge, Dedhar’s journey back will take a little longer.

“Lots of slow, boring walks up forest roads for a while and a fairly good amount of nice, easy greens and blues on the resort for a bit before I’m back in the mountains skiing backcountry terrain, but I definitely plan to be back,” he admitted.

‘We’ve got to respect the mountains and listen to what they’re telling us’

Balancing that stoke with personal responsibility is crucial to a successful day in the mountains, if you ask Squamish-based mountain guide Evan Stevens.

“Part of the joy in the mountains is going to do new things and be challenged by those places, but you have to have the experience and the skills to know you can comfortably manage it, and set yourself up with expectations that are in line with the conditions,” he said.

“It’s awesome that we have this amazing access to unbelievable mountains all around us, but at the end of the day, we’ve got to respect the mountains and listen to what they’re telling us. We’ve just got to come prepared for all eventualities and we’ve got to understand that our actions might not just have consequences on ourselves, and that if we do get into trouble out there, you could be putting other people at risk who just want to help us out.”

Organizations like the British Columbia Mountaineering Club or the Alpine Club of Canada are great places to find mentors or a group that can serve as a sounding board for decision making and help you identify any knowledge gaps.

Aside from taking avalanche, mountaineering, glacier travel and crevasse rescue courses, Stevens also recommends working your way up to larger, higher-consequence objectives like Wedge with smaller stepping stones.

“You can’t force your agenda on the mountains,” he said.

As the International Federation of Mountain Guides- and Association of Canadian Mountain Guides-certified owner of Zenith Mountain Guides, Stevens’ initial reaction after hearing about the incident at Wedge was, “How did these people get here?” he recalled. “The second reaction is that these are two of the luckiest humans around, that they are alive at the end of that day.”

Don’t follow the blue dot

Armed with a background in cartography, Stevens recognizes mapping apps as an “unbelievable asset and a tool” in the backcountry. But especially considering how much terrain, routes and glaciers can change from day to day, week to week and season to season, “nothing can replace experiential knowledge,” he explained. “You need field time, in a variety of times a year, in places and conditions to just be able to read the nuances of the terrain.”

The incident at Wedge prompted Whistler Search and Rescue to issue a reminder to the backcountry community that the “first and foremost consideration in any travel route should be your exposure to risk. Getting there safely should be your only objective.

“Make a point of learning and incorporating situational awareness when travelling in wilderness settings,” the statement continued.

“Be aware that the blue dot is capable of seducing you into complacency by pretending to inform you of where you are. Remember… It is just a [blip] on a screen and bears little reference to the situation you are actually in. Take the time to properly plan your trip, get the pertinent info and conditions, choose appropriate, knowledgeable and risk-averse adventure partners. Be patient, one day the perfect conditions for that prized objective will present themselves. There are plenty enough other objective dangers that will snag you without adding haste to the list.”

Dedhar encouraged anyone who is beginning their backcountry journey to learn from his experience, and from others’ cautionary tales. “But at the same time, don’t be dissuaded from trying,” he added. “There are great resources out there to help you try things the right way, but I think the rewards are awesome. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be trying to go back as soon as I can.

“And for anyone who’s more experienced out there, if you have the capacity to try to be that mentor for someone else, it’s an awesome thing to do. And you can help people not be me.”