Being on income assistance makes a person almost 2 1/2 times more likely to die during a heat wave, according to a new study from the BC Centre for Disease Control.

Researchers looked at heat-related deaths from the 2021 heat dome that killed 740 British Columbians and found that poverty and several chronic diseases put people at a higher risk of dying.

Schizophrenia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Parkinsonism (which includes Parkinson’s disease and other related conditions), heart failure, chronic kidney disease, ischemic stroke and substance use disorder also all significantly increase a person’s risk of injury or death during high temperatures.

Those who are “most at risk are often people who don’t have means to adapt personally, in family or community, to extreme temperatures,” said Sarah Henderson, one of the study’s authors.

Henderson is the scientific director for environmental health sciences at the BCCDC and an associate professor at the University of British Columbia school of population and public health.

“No one is at risk from extreme heat if they have safe indoor temperatures,” she added, noting that the majority of heat deaths happen in private residences.

If you have chronic health conditions and access to cool indoor spaces or are healthy but have warm indoor spaces, then you may be extremely uncomfortable but survive, she said.

“But if you have poverty and any of these conditions, then you may be more than uncomfortable.”

The 2021 heat dome, when temperatures climbed 16 to 20 C above seasonal norms between June 25 and July 2, 2021, was the deadliest extreme weather event in Canada’s history.

The deadly temperatures would have been “virtually impossible” without human-made climate change, according to a report by World Weather Attribution.

Lytton made headlines for hitting the hottest outdoor temperature ever recorded in Canada at 49.6 C, with Kamloops, Abbotsford and Quesnel also hitting 47.3, 42.9 and 41.7 C, respectively.

“If you can’t afford air conditioning or you can’t afford to run the air conditioner because the cost of energy is so high, then the risk is your indoor environment puts your health and safety in danger,” Henderson said.

Following the 2021 heat dome, B.C. launched a program that provides low-income households with a free portable air conditioner.

The Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation said it has distributed 15,000 units so far, with more than 75 per cent installed in the Lower Mainland.

The government has committed to distributing 28,000 free air-conditioning units.

When asked why the government is distributing air conditioners instead of heat pumps, which also filter the air and could protect people with COPD from poor air quality, the ministry said in an email the air conditioner program is “designed to help people who are most vulnerable during heat emergencies — those who are low income and ‘medically heat vulnerable.’ This is meant to be an immediate solution to support these individuals.”

The ministry also pointed to its CleanBC Better Homes Energy Savings Program, which offers rebates for buying heat pumps.

“Through this expanded program many families can switch to a free heat pump without needing to pay up front,” the ministry wrote.

The ‘quadruple whammy’ of poverty

Poverty impacts people’s health in several ways, in what Henderson calls the “quadruple whammy.”

Being unable to afford life-saving technology to keep oneself and one’s family safe during extreme weather compounds with the chronic stress from living in poverty, which can create health conditions that put an individual at higher risk from extreme heat.

“We know people living in poverty are not as healthy as those not in it,” she said.

Then you add how many impoverished people in B.C. are socially isolated and living in poor-quality housing that doesn’t protect them from the heat.

Often, people living in poverty can only afford to live in older buildings with single-pane windows “that collect heat like nothing else on this Earth,” don’t have thermal curtains and are located in all-concrete, no-shade areas, Henderson said.

Age, mental illness and pharmaceuticals affect heat perception

Older British Columbians and those using certain pharmaceuticals are also harder hit by heat waves.

As people age, their bodies’ ability to thermoregulate changes and they might not notice until they’re in trouble, Henderson said. Older people can also perceive heat differently, which can put them at risk if they don’t feel sick and realize they need to cool down.

All age groups over 50 saw a doubling of mortality during the heat dome, Henderson said.

Certain pharmaceuticals can also impact a person’s ability to thermoregulate or affect their perception of heat, she added.

Chronic diseases also put people at higher risk of death during extreme heat events. However, it’s often where these chronic diseases intersect with poverty that puts people at greater risk, Henderson said, adding that everyone should have access to safe indoor temperatures.

Schizophrenia made a person nearly two times as likely to die during an extreme heat event, according to the research.

Poverty and social deprivation can feed into these risks, said Randall White, a clinical professor in the UBC department of psychiatry.

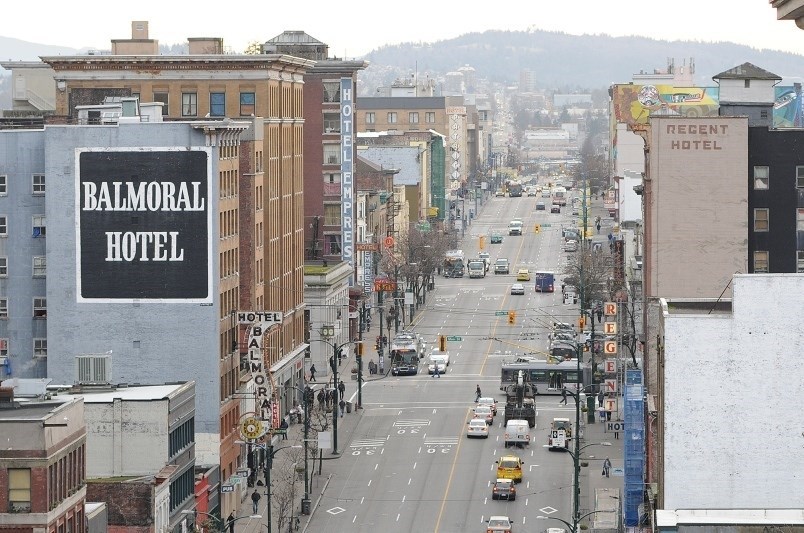

People with chronic mental disorders are often unemployed and receive disability assistance payments. But these payments are so low that people are forced to rent substandard housing such as single-room occupancy hotels, which rarely have air conditioning, White said.

People’s behaviour can come across as “bizarre” and schizophrenia is stigmatized so “their social circles can also be impoverished,” White said. This can mean no one checks on them during extreme heat.

Physiologically, people with schizophrenia may not be aware of their internal state or may not notice they need to drink water or cool down, he added.

Pharmaceuticals can also play a role. White noted that antipsychotics can impact a person’s ability to thermoregulate and antidepressants can reduce a person’s sense of thirst.

Agencies like the BC Schizophrenia Society have implemented extreme-heat protocols after the 2021 heat dome, Henderson said. These include increasing the number of home check-ins during high temperatures.

Increased risks for those with COPD, Parkinsonism and heart failure

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a lung condition that was likely made worse due to the elevated levels of ground-level ozone and fine particulate matter that happened at the same time as the heat dome, the study said.

Having COPD, Parkinsonism or heart disease made people almost 1.5 times more likely to die during the heat dome.

Heart failure signals that a person’s heart isn’t working well and they’re likely on a suite of medications, Henderson said. The heart is the body’s primary mechanism for cooling because it pumps blood to the skin. If your heart isn’t working well, then your body may struggle to cool itself.

Medications taken for Parkinsonism can impact thermoregulation, Henderson said.

Chronic kidney disease made people 1.4 times more likely to die, ischemic stroke 1.3 times more likely and substance use disorder 1.1 times more likely to die during the heat dome, the research said.

Staying hydrated is another key way to stay safe, Henderson said. When your kidneys aren’t working properly, this can impact the fluids in your blood, which hurts the body’s ability to cool down.

An unrelated study from 2019 found chronic exposure to high temperatures could increase a person’s risk of dying from kidney disease by 30 per cent.

If a person has had a stroke, they may have mobility issues or take pharmaceuticals that impact thermoregulation, Henderson said.

Substance use could be related to higher mortality because some people were intoxicated during high temperatures and unable to respond, or their substance use disorder could signal they had other health issues, Henderson said.

White said he and Liv Yoon, an assistant professor at the UBC school of kinesiology, interviewed 35 people with schizophrenia and asked them how they coped during the 2021 heat dome. The research is currently being peer reviewed and has not yet been published.

But in those interviews, he heard people used substances to deal with their stress and discomfort during the extreme heat.

Alcohol and benzodiazepines can reduce people’s awareness or even make them pass out, which means they can’t respond to extreme heat. Amphetamines increase a person’s level of activity, which generates more internal heat, White said.

Adjusting for low income

When the risks associated with schizophrenia and substance use disorder are adjusted for low income, both risks decrease. That shows that some of the risks associated with schizophrenia and substance use disorder are actually due to poverty, Henderson said.

The study compared 1,597 adults who died between June 25 and July 2, 2021, with 7,968 adults who survived, and looked at differences in chronic disease and social vulnerability between the two groups.

B.C. has a free online that explains how to make an emergency plan, what symptoms to watch out for during extreme heat and how to stay cool during extreme heat events.