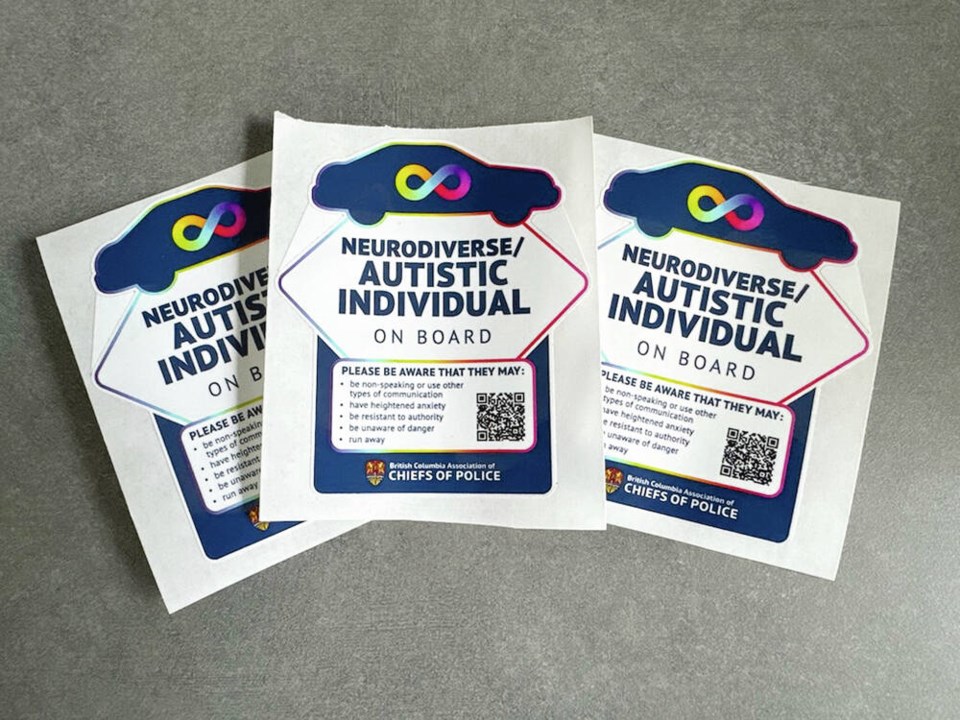

A new decal that can be put on vehicles or homes to indicate someone has autism so police officers adjust their response is much needed, say advocates.

The decals, which have been given to police departments across the province for distribution to the public, indicate a neurodiverse or autistic individual is in a vehicle or lives in a residence.

It asks officers to be aware that the person may be non-verbal or use other types of communication, may have heightened anxiety, may be resistant to authority, may be unaware of danger and may run away.

“The decals will be able to tell the officers at car traffic stops and going to a home, you may not get the reaction you expect. So you have to re-evaluate how you’re going to approach this person,” said Const. Sherri Wade of Nanaimo RCMP, which is embracing the by the B.C. Association of Chiefs of Police and the B.C. Law Enforcement Diversity Network.

A one-hour online training program is being developed that will be available to officers across the province to better understand Autism Spectrum Disorder.

The goal of the training offered by Pacific Autism Family Network is to help officers learn how to recognize behaviours and responses associated with being on the spectrum, learn communication skills for interacting with people on the spectrum and understand how to gain co-operation with people who are neurodiverse.

A 2023 incident in which a 12-year-old boy with autism was handcuffed in B.C. Children’s Hospital highlighted the need to look for ways to improve interactions between officers and neurodiverse people, said Tiffany Parton, executive director of the B.C. Association of Chiefs of Police.

A mother recorded officers holding her son on the floor of the hospital in handcuffs. The two had been taken there by officers who were called because the boy was “pushing” at a Sky Train station, she told The Canadian Press at the time.

They had been to the hospital before and her son became upset because the room they had waited in during other visits wasn’t available. She said officers pinned him to the floor “at the first sound of his whining,” without asking him to calm down.

It was an incident that could have had a better outcome if the officers had reacted differently, Parton said.

“If you know someone is living with autism and they don’t comply, your response is different to that individual instead of just instantly putting them in handcuffs. There’s just a different way to engage,” she said.

Wade, an officer with Nanaimo RCMP’s vulnerable persons unit, said someone who is neurodiverse and becomes overstimulated might shut down in a way that makes officers perceive them as defiant.

“The person we’re talking to could act in a way that we might even feel threatened by because we’re not getting the response we expect,” she said.

The decals are a visual reminder to slow down and adjust their approach, keeping in mind someone might be sensitive to touch or sound, she said.

Wade said she has experienced firsthand the importance of interacting with someone in a way that works for them, citing an incident with a young woman who was having a mental-health crisis. She had been the subject of calls previously, but there was no information about how she wanted to be dealt with, Wade said.

“When I came in the house, she actually just gave me a card. She had come up with that with one of her support workers and that was extremely helpful, because it clearly outlined how she needed to be treated in order not to escalate [the situation],” she said.

The card provided information on the woman’s physical triggers and the tone of voice she needed, and helped the interaction go smoothly, Wade said.

Victoria police have decals at their 850 Caledonia Ave. headquarters and their office in Esquimalt at 1231 Esquimalt Rd. They can be picked up Monday to Friday between 8:30 a.m. and 4:30 p.m.

Saanich police have received the decals but say they are not quite ready to distribute them to the public. The department is in the process of creating a plan for distribution.

Wendy Lisogar-Cocchia, co-founder of the Pacific Autism Family Network, said the non-profit was happy to partner with the B.C. Association of Chiefs of Police to create “this meaningful way for police to address the unique needs of the autism and neurodiverse population.”

Giving people on the spectrum and their families a way to shape their interactions with police will give them “a sense of peace,” she said in a statement.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]