Pesticide and air pollution exposures may be contributing to a spike in childhood inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn's disease, across several B.C. communities, a new study has found.

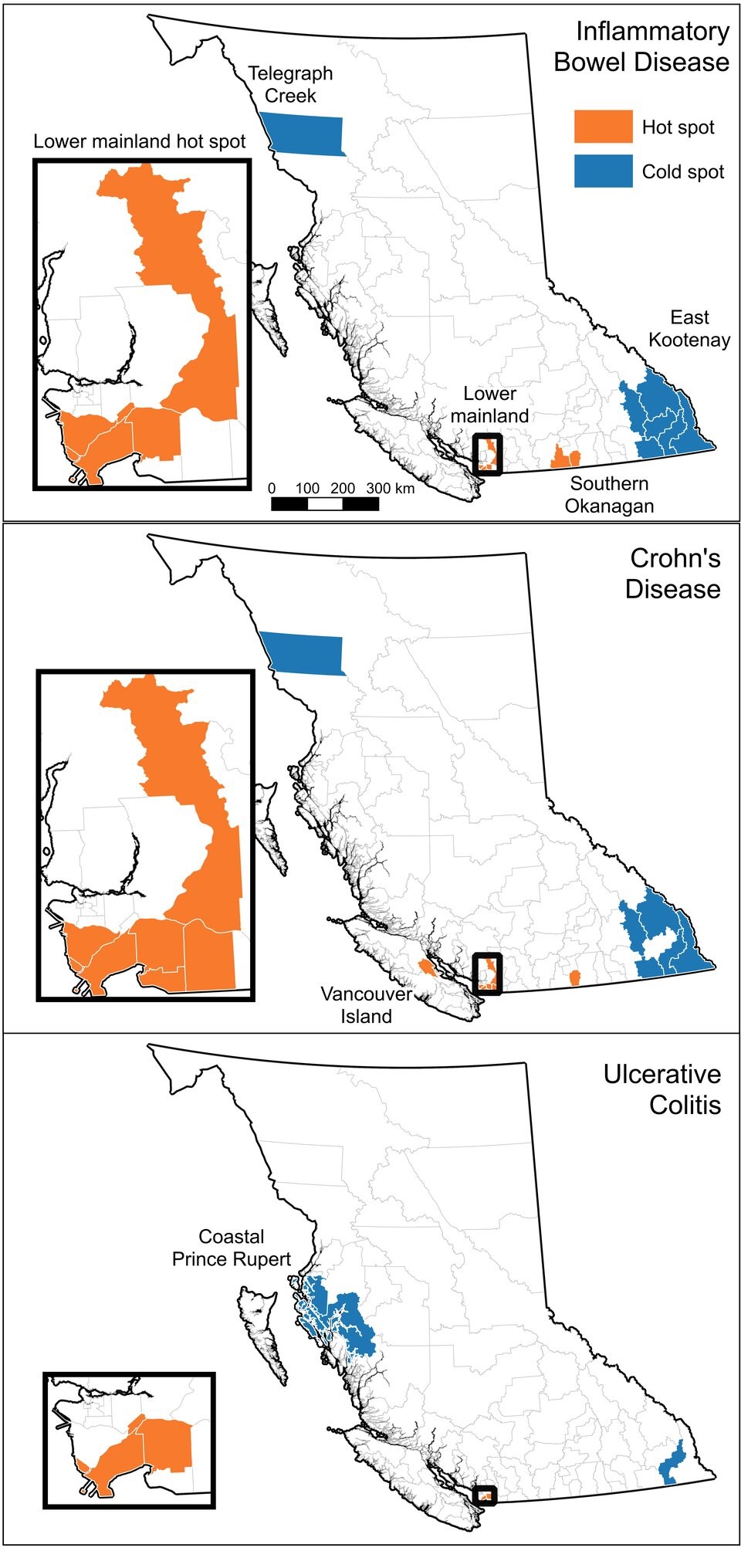

The , recently published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, points to a number of hot spots across the province, including suburban Metro Vancouver, the Okanagan Valley and Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island.

Dr. Kevan Jacobson, a gastroenterologist at B.C. Children's Hospital and a supervisor on the study, said the hospital is currently treating more than 900 children for childhood inflammatory bowel disease — a spectrum of diseases known as IBD that includes Chrohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

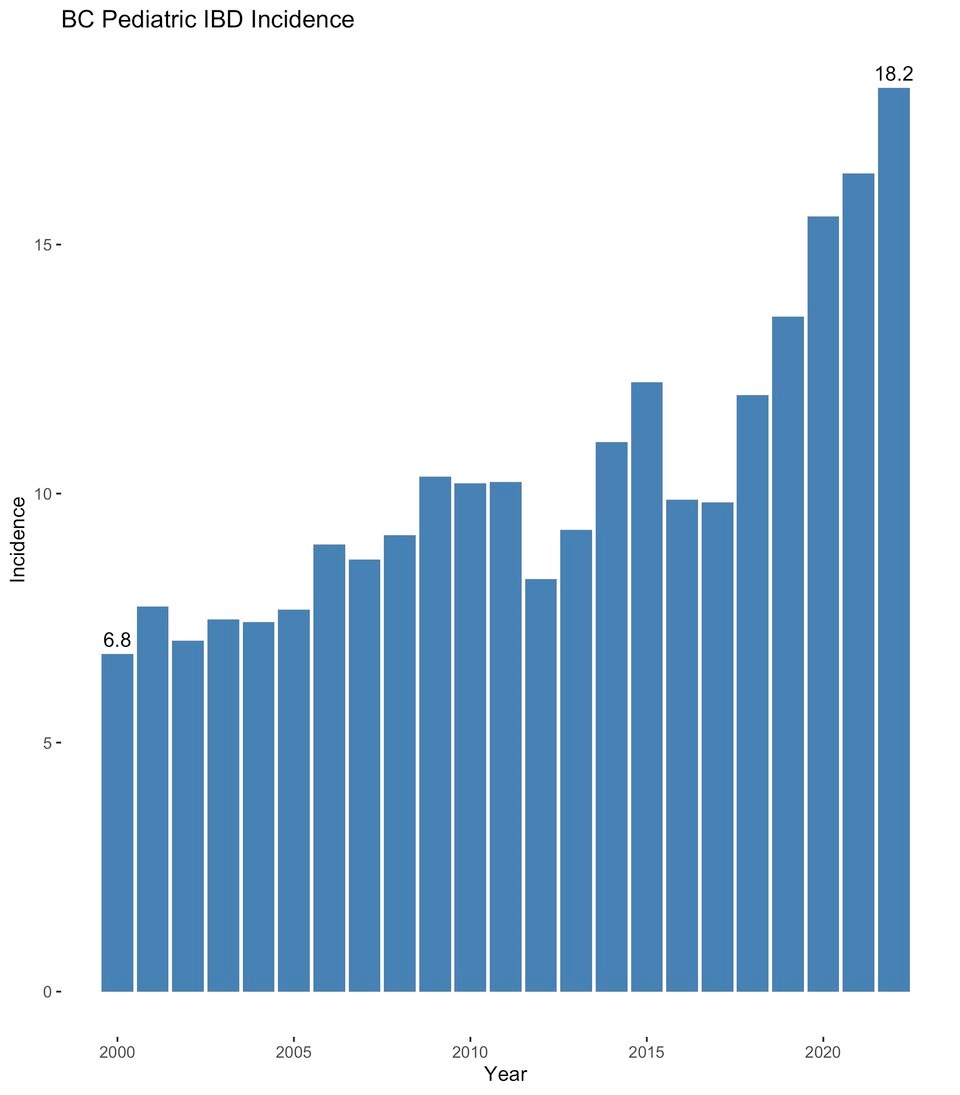

In the last few years, annual new cases have doubled, spiking to roughly 160 new cases in 2022, and joining the rest of Canada as a country with one of the highest rates of IBD in the world.

“We've seen a significant rise number of kids that we see,” said Jacobson.

Most IBD cases in B.C. are either diagnosed as ulcerative colitis, which causes bloody diarrhea, frequent bowel movements and a lot of abdominal pain, or Crohn's disease, a “much more insidious” condition that leads to slower onset abdominal pain, poor weight gain or loss, and chronic diarrhea, Jacobson said.

While there is a growing spectrum of medicines that can limit IBD symptoms, the diseases can't be cured and often lead to relapses throughout a lifetime.

As researchers look for solutions, the first-of-its-kind B.C. study offers a window onto what's causing the surge in cases across some parts of the province.

“We are the first study to identify agricultural pesticides as a potential cause of inflammatory bowel disease,” said lead author Mielle Michaux, a medical geographer at B.C. Children's and the University of British Columbia.

“We found a link between areas where we have more IBD cases and areas where we have higher population exposure to petroleum [pesticides] used in orchard and grapes. You see that a lot in the Okanagan, where there's a lot of fruit production.”

Another high risk factor for the disease, said Michaux: exposure to fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5.

“It can come from construction, from combustion from cars, but a major source of very high exposure events is wildfires,” she said.

B.C.'s farmland and suburbs hit hardest by disease

The research involved six experts from UBC, the University of Indiana and BC Children’s Hospital. Together, they drew on techniques in medical geography and ecological analysis to pinpoint different risk factors for the disease.

Using data from 1,183 patients who attended B.C. Children’s Hospital, the group examined spatial clusters of the disease, based on postal codes, from 2001 to 2016.

On the ecological side, they analyzed the disease prevalence and how it correlated with a national data set that included ethnicity, family size, income, urban versus rural living, as well as exposure to the sun, green space, pesticides and air pollution.

The study found significant spikes of the childhood bowl disease in the South Okanagan, Comox Valley on Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island, and in the eastern and southern reaches of Metro Vancouver, including Delta, White Rock, Surrey, Langley and New Westminster, as well as Maple Ridge in the Fraser Valley.

“Other studies in Canada often identify the very densest urban areas as hot spots for IBD,” said Michaux. “But for us, we're seeing, rather than say a very dense urban area of Vancouver, we're seeing some of the more suburban areas adjacent to that.”

Low incidences of the disease were found in southeastern B.C. and northern B.C., and on stretches of the coast.

South Asians children face higher disease rates

The study also found people of South Asian ancestry faced a higher risk for IBD. Jacobson said that was a curious finding because, while genetics is also thought to play a role in prevalence of the disease, very few South Asian children have a family history of inflammatory bowel disease when compared with kids of Western European ancestry.

Those who identified as Indigenous, on the other hand, were found to be at a lower risk, something Jacobson said could be a result of genetic protection or a different diet or lifestyle.

“It comes back to the environmental factors. You know, what we put in our mouths, and what we can be exposed to around us and what we inhale,” said the doctor.

The researchers say their findings are not a cause for panic, but should spur more science into how exposure to agricultural pesticides and air pollution are impacting peoples' health.