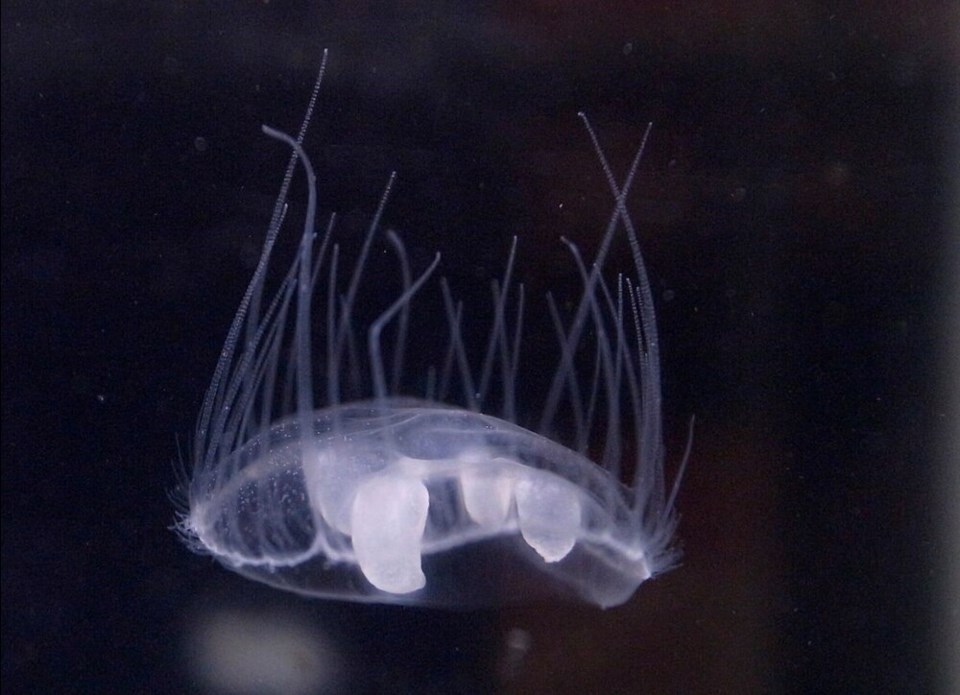

It may only be the size of a human thumbnail, but with up to 500 tentacles and an arsenal of poisonous harpoons, the hydromedusa has at least one B.C. scientist concerned.

Native to the Yangtze River valley in China, the tropical freshwater jellyfish — also known as the peach blossom fish or Craspedacusta sowerbyi — has hitched rides across the world over the past century, popping up as an in watersheds across Russia, Australia, South America and the United States. In Canada, the jellyfish had been spotted in southern Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes.

Then, in the summer of 2020, zoologist Florian Lüskow got a report from a local resident on Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island — they had found something at Killarney Lake on the edge of Mount Work Regional Park.

“I travelled to this tiny lake on Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island close to Victoria,” said the University of British Columbia PhD candidate. “I found it’s not like one or two jellyfish… it’s like hundreds of thousands.”

Since then, the reports continue to come in.

When he published his last year, Lüskow found sightings of the jellyfish stretching back at least 30 years, but since 2010, the number of people who spotted hydromedusae spiked dramatically.

The researcher suspects that with enough eyes on the province's lakes and reservoirs, he will be able to track just how widespread Craspedacusta sowerbyi are in B.C.

From there, he hopes to track the damage they are causing.

Watch your eyeballs and open wounds

You may have encountered a hydromedusa and not even known it. Unlike some jellyfish, their cnidocyst cells — which explode venom into prey on contact — can paralyze small fish, but aren’t powerful enough to penetrate human skin.

The human weak points, says Lüskow, are when the jellyfish swim into our eyes, say when they get trapped in goggles or a mask, or when their harpoons come into contact with an open wound.

“I have seen a couple of incidents on Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island,” he said. “These two kids needed to go to the hospital.”

After a week or so of antibiotics, however, people usually recover.

What’s more worrying, says Lüskow, is the risk the hydromedusa poses to the multiple freshwater ecosystems it appears to have invaded.

On the cusp of a global jellyfish explosion

Jellyfish tend to like warm water. For the hydromedusa, that means it’s usually only seen in the summer or fall.

In the colder months, the jellyfish can survive as colonies of dormant polyps, tube-like organisms that attach to debris on the lake bed and wave their camouflaged mouth at prey as it drifts by. When conditions warm, the polyps wake up and start producing blooms of jellyfish again.

But just how often that happens could be changing as climate change keeps lake temperatures warmer for longer.

“We expect that the temperature [in B.C.'s lakes] is getting warmer. Summers are probably getting longer, which paves the road for species like this jellyfish,” said Lüskow.

Last November, Lüskow and his colleagues published a first-of-its-kind study in the journal Scientific Reports, with modelling indicating the freshwater jellyfish would see explosive growth across many of the world’s ecosystems, invading high-latitude regions in Eurasia and North America, “with ecological consequences in already threatened freshwater ecosystems.”

No previous study had described the species' global distribution or how it was changing due to climate change.

Their found changes in precipitation, vapour pressure and temperature would drive an explosive period of growth over the next 30 years.

The biggest future hot spots were found in Canada and the U.S., as well as South America and Europe, where the jellyfish species is expected to expand its range by between 52 and 84 per cent. On North America’s west coast, even the lowest emission scenarios showed the hydromedusa’s habitat encompassing much of B.C., and stretching from coastal Alaska down to Southern California.

Aquarium dumping, dirty boats and waterfowl to blame

Today, however, it’s not clear how hydromedusa are spreading or even how the jellyfish arrived in B.C.

Lüskow suspects aquarium owners are partly to blame. Hydromedusa have been found in fish tanks, and when dumped out, they could easily make a new home in a local lake or pond.

From there, waterfowl are thought to pick up dormant polyps as they feed, and spread them to other lakes when they defecate or dip their beaks back in the water. In other cases, the polyps are thought to have attached to the hulls of boats, catching a ride from one lake to another with the owner.

“Without any food, fresh oxygen, they can basically just shut down and wait it out,” said Lüskow.

When the conditions are right, the jellyfish population could all of a sudden bloom, finding itself in a much bigger world.

​Once in a new lake, past studies have found hydromedusae feed on a number of larger zooplankton species, firing poison into its prey before coiling a tentacle around it and dragging the paralyzed victim to its mouth.

Some researchers have seen evidence the polyps feed on striped bass larvae, others speculate the invasive jellyfish consumes fish eggs.

Lüskow says the hydromedusa could be feeding on zooplankton to the point where fish have a hard time competing and struggle for a few weeks before recovering. Or maybe the impacts linger for weeks, months or even longer.

Whatever the case, he says the chances of finding the creature in B.C. is growing.

“We’re not as bad as the zebra mussel in the Great Lakes, which basically has spread all over, replaced local species and messed up the aquaculture.”

“It's not that bad yet, but we don't know where we're going.”

Tracking jellyfish invasion requires army of volunteers

Lüskow says there is a lot of educated guessing going on. That's where the public comes in.

To track the freshwater jellyfish and fill in the data gaps, Lüskow is calling on residents of B.C. to help spot the invasive species — especially in less densely corners of the province where the odds of someone spotting a hydromedusa are lower.

“Maybe they are already in the Interior or close to Port Hardy on Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island. We just don’t know that because nobody reported anything. But the absence of reports doesn’t mean there is no presence of this species,” said the researcher.

To find them, Lüskow says the best bet is to visit B.C.'s fresh water bodies from July to September. The little jellyfish usually move very quickly, pumping up to the surface before floating to the bottom of the lake.

Look for the classic bell shape of a jellyfish — only instead of eight to a half-dozen tentacles, you’ll see hundreds.

“They look a little bit messy,” said Lüskow.

***

If you find a hydromedusa, email Florian Lüskow at [email protected].

Observers are asked to share the place, time, conditions and “if possible, even a picture of the jellies,” said Lüskow.