Scientists at Environment Canada are working on a system to quickly tell the public how much an extreme weather event was made worse by climate change, Glacier Media has learned.

Known internally as the Rapid Extreme Event Attribution Project, scientists from Victoria, Toronto and Montreal first got funding for the project in November 2022, as part of Canada’s National Climate Adaptation Strategy.

“We hope to have a prototype in place a year from now,” said research scientist Nathan Gillett, who’s leading the group.

“From a communication perspective, people are interested in the event shortly after it occurs, or while it’s occurring. It helps people understand how climate change is affecting them.”

The project is part of a larger federal effort to bring more transparency to the effects climate change is having on Canadians. Other projects to bring “locally-relevant information” to residents across the country include , a climate portal that allows people to “access, visualize, and analyze climate data” and “tools to support adaptation planning,” a spokesperson for Environment and Climate Change Canada said.

Rising pressures from heat and floods

Gillett says the extreme event system would attribute the impact of climate change on everything from extreme rainfall to blistering heat and cold.

In B.C., modelling suggests the province will face increasingly wet winters, with more rainfall falling in bursts during extreme events. Just how that will raise the risk of floods is currently being assessed through new national flood maps currently under development.

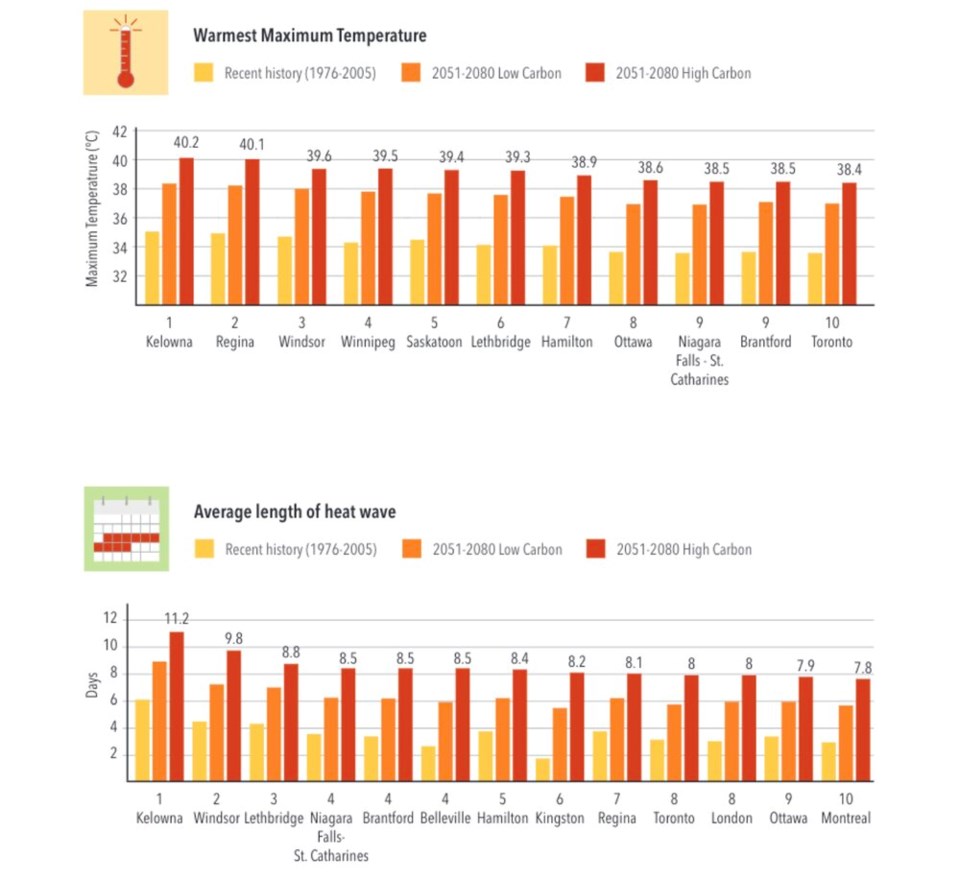

Meanwhile, many communities across B.C. are expected to see a precipitous rise in temperature. A report last year from the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation found that in the last half of this century, Kelowna is likely to see the warmest maximum temperatures and longest heat waves of any major city in Canada.

Smaller Interior communities like Kamloops, Penticton, Creston and Vernon are also expected to reach similar temperatures.

Whereas flooding and wildfire — expected to increase in frequency and intensity this century — will cost Canada vast sums of money, heat waves will ramp up as a kind of silent killer.

“The impacts of heat are death,” Joanna Eyquem, lead author and managing director of the centre's Climate Resilient Infrastructure, said at the time.

Understanding how much (or how little) climate change influenced an extreme event also serves as a tool for policymakers. After disastrous floods, politicians and bureaucrats need to know the probability of an event returning under certain climate conditions. That way they can plan infrastructure upgrades to handle future flooding or extreme heat.

Making extreme event attribution a 'push and play' solution

The science underpinning climate attribution has exploded over the past two decades.

Scientists first published an extreme event attribution in 2004, more than a year after a heat wave hit Europe. But it wasn't until 2015, in the wake of another European heat wave, when researchers from France, the U.K. and the Netherlands launched , an umbrella organization that now brings scientists from across the world to quickly assess the impacts of climate change on extreme weather.

To find the fingerprints of climate change on an extreme weather event, scientists first need observational data — like temperature and precipitation — often going back well over 100 years in some cases. Climate scientists then run that data through computer models under two scenarios.

In one case, they model a "counterfactual world" where humans have not belched vast quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere; in another, they model the planet's current lived reality, calculating how much fossil fuels have shifted the odds of such an event.

Whereas earlier attempts took up to a year to get results, in WWA's first attempt, it carried out the complex investigation within weeks of the heat wave. Since then, scientists working through the global initiative have published dozens of studies, attributing the impacts of climate change on hurricanes in the U.S., drought in East Africa, and typhoons in Japan.

After the summer of 2021, the spiked temperatures across B.C., Alberta and the American northwest — killing hundreds of people and devastating wildlife — scientists working through the WWA found human-caused climate change made the extreme heat event 150 times more likely.

The study, which took a week, suggested the heat wave was extremely rare, representing a one in a 1,000-year event in the present climate, according to Faron Anslow, one of 25 co-authors and then a Victoria-based climate scientist from the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium.

“We didn’t think we’d be here right now,” he told Glacier Media at the time.

When an atmospheric river triggered , rocking the province only a few months later, Anslow would later collaborate to quickly assess the event was made two to four times more likely because of the changing climate.

But those studies, which often involve scientists from several countries, are selective, and often only focus on the most extreme cases at a global level.

A made-in-Canada attribution system would regularly make the hard task of imagining a changing climate more tangible — over and over again. If you know a storm you just lived through is made four times worse because of climate change, it's easier to get a grip on a changing world, the thinking goes.

“Things that have had an impact on you recently, you’re more aware of those,” said Gillett. “It’s just the way humans are.”

The extreme event attribution system will act as a template where a variety of weather data and global climate models are fed into a single hub. Some events might require scientists to go out and collect more data.

In many cases, there will be limitations. Not having enough observational data or computing power to run small-scale models already make it more challenging to attribute the impacts of climate change on phenomenon like hurricanes, thunderstorms or tornadoes.

But Gillett says his and other teams are making progress. In the coming years, as scientific methods and technology advance, the idea is to have a attribution engine ready to go before disaster strikes.

“You pretty much push the button and you get results,” he said.

Gillett said the final system is still two to three years away, and before then, the Victoria-based scientist says they are planning on going to local communities for input to better improve its design.

“How it’s going to look to the public? That’s something we still need to work on.”

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)