As construction of B.C.’s newest pipeline got underway in late August, with route clearing in the northwest, Indigenous leaders burned a pipeline agreement and set up an on-going blockade.

The 800-kilometre Prince Rupert Gas Transmission (PRGT) pipeline would ship natural gas from northeast B.C. to a proposed liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility on the northwest coast. Conflict over the pipeline is growing as Indigenous and non-Indigenous leaders in the region oppose the project on the ground and in the courts.

Neither the pipeline project nor the roots of the conflict are new. Both have complicated histories that span more than a decade and thread through multiple governments.

John Rustad, current leader of the BC Conservatives, was Minister of Aboriginal Relations in the early 2010s when the province set plans in motion for a proposed massive expansion to B.C.’s natural gas sector. Tasked with getting First Nations to agree to pipelines to enable that expansion, Rustad set out to negotiate agreements with Indigenous leaders across the north — agreements now lighting the fires of conflict under the pipeline project.

As a key decision about the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline looms, the party that forms government following the Oct. 19 B.C. election will face a quagmire of conflict and tough decisions about how to navigate the unfolding situation.

The Narwhal dug into the complicated history behind the conflict, connecting the dots between political parties, industry and government deals. Here are five key takeaways.

How is the PRGT conflict related to Coastal GasLink?

The agreements and approvals for the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline happened around the same time as those for the Coastal GasLink pipeline. Until recently, both projects were owned by the same company, multinational pipeline giant TC Energy.

When construction on Coastal GasLink got underway in 2019, B.C. quickly became a focal point for conflict between industrial development and Indigenous Rights. The B.C. government and TC Energy had signed deals with five of six elected Wet’suwet’en band councils but did not receive free, prior and informed consent from Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs, who opposed the pipeline.

In early 2020, the world watched as Wet’suwet’en opposition to Coastal GasLink led to Indigenous-led solidarity protests that shut down railways and ports across the country. It was a flashpoint that signalled growing frustration with carbon-intensive resource extraction proceeding without consent from Indigenous leaders, held in stark contrast against political commitments to reconciliation and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Conflict over the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission project is a bit different, because agreements were signed with a mix of elected band councils and some Hereditary Chiefs across the north. But it’s been 10 years since the ink dried and some Indigenous leaders believe the pipeline should be subject to a new environmental assessment — or scrapped entirely.

Making things more complicated, TC Energy sold the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission line to the Nisg̱a’a government and its industry partners earlier this year. The Nisga’a government says the pipeline — along with the proposed Ksi Lisims LNG project it co-owns that the pipeline will supply — will help build economic prosperity.

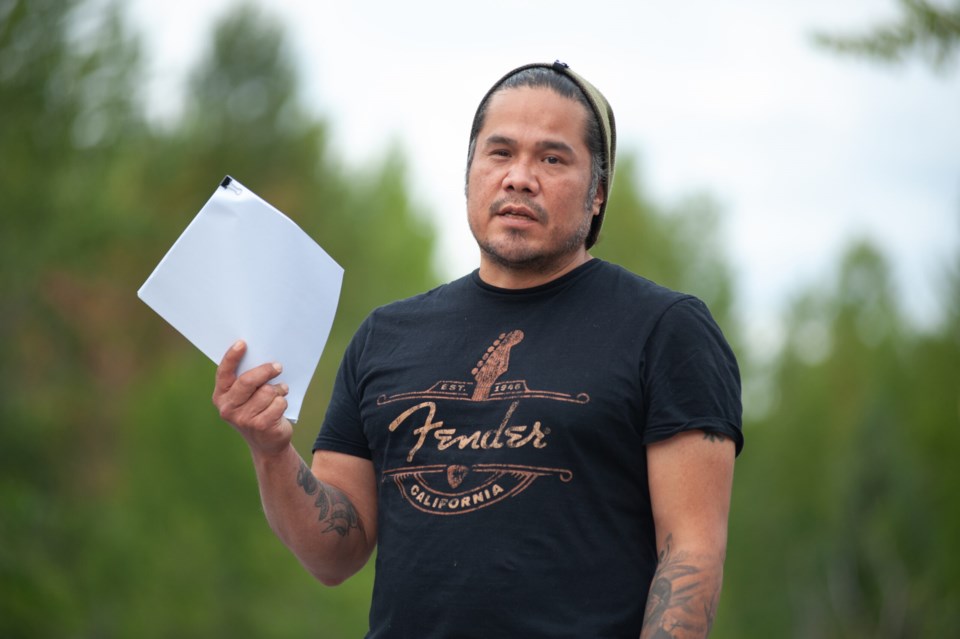

In late August, as construction began on Nisga’a territory, Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs burned agreements and set up an on-going blockade to stop traffic related to the project from crossing their territory. Indigenous leaders have said they plan to take whatever action is necessary to stop the project.

“​​I think everyone has the Coastal GasLink scenario in mind in the context of what is developing around PRGT,” Gavin Smith, lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law, told The Narwhal. He said if the project proceeds, he anticipates “very pronounced opposition.”

Where do B.C.’s political parties stand on LNG?

It’s a two-party race to form government between the Conservatives and NDP. Both support expanding the LNG sector.

Rustad is vying for the premier’s office on a platform promising to accelerate development of fossil fuel infrastructure in the province. The BC Conservatives have promised to “dramatically expand” B.C.’s natural gas production and LNG export facilities, touting the oft-repeated narrative that natural gas will displace more carbon intensive coal-fired electricity in other countries.

That narrative is widely disputed by critics, who point to how countries like China, frequently cited for its reliance on coal for energy production, are outpacing most in developing renewable energy projects.

While the BC NDP doesn’t use the same language as the BC Conservatives, it offers much the same narrative.

In an interview with Bloomberg this summer, BC NDP Leader David Eby said it’s possible to double initial production at the country’s first LNG export project, LNG Canada, while still meeting the province’s climate goals. LNG Canada, which will be supplied by the Coastal GasLink pipeline, is slated to commence export operations next year in Kitimat, B.C.

How will the B.C. election affect how the conflict unfolds?

David Tindall, a professor in the University of British Columbia’s sociology department, said the new pipeline being co-owned by the Nisga’a government will influence the B.C. government’s response to potential conflict, no matter which party wins the election.

He said he’s seen a trend where the NDP “is partly trying to do certain types of extractive development,” typically subject to opposition from environmental activists, “by facilitating these kinds of projects when they’re owned or run by First Nations communities.”

The response would look similar if the BC Conservatives form government, he added.

“If the Conservatives win the election, I would see them being a little bit more inclined to pick winners and losers and back the pipeline owners and basically oppose any groups that are opposed to the pipeline.”

Earlier this year, the BC Conservatives pledged to hold “activists who impede the activity of resource development through illegal blockades” accountable — a promise later quietly scrubbed from the party’s website.

What are the climate impacts of the PRGT pipeline?

The brewing conflict is a distraction from the real issue, according to Naxginkw Tara Marsden, a Gitanyow member from Wilp Gamlakyeltxw who works with the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs.

“We’re stuck in this cycle of people only paying attention when it’s that really heated, race-based conflict and the fact that this is nation to nation is even juicier,” she told The Narwhal. “But that’s not the story — the story is the climate is going to kill us all.”

Natural gas is mostly composed of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide for its short-term warming impact on the planet. Methane is invisible and odorless, which means leaks are notoriously hard to detect. And every step of the process of extracting the fossil fuel for energy production — including the wellhead, pipeline, liquefaction, shipping, regasification and combustion — adds more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, intensifying the effects of climate change.

A recent study in the journal Energy Science and Engineering calculated the climatic impacts of the full lifecycle of getting gas out of the ground and shipped overseas to be burned for energy production. The study, authored by Robert Howarth, a Cornell University environmental scientist, concluded natural gas exported from the United States produces 33 per cent more greenhouse gases than coal.

“To think we should be shipping around this gas as a climate solution is just plain wrong,” Howarth told the Guardian.

What’s next for the PRGT pipeline?

The new provincial government must decide whether or not to require a new environmental assessment for the pipeline project. It will consider work done on the pipeline until Nov. 25 in its decision about whether to lock in the project’s original environmental assessment certificate indefinitely — by granting what’s called a “substantially started” designation or require a new assessment.

When the pipeline received government approval in 2014, B.C. gave a green light to a route ending in Prince Rupert. But the route was changed in an amendment application filed with the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office in June.

Instead of going to Prince Rupert, the pipeline’s proposed final destination is now the as-yet-unapproved Ksi Lisims LNG project on B.C.’s north coast, near Alaska. Smith, with West Coast Environmental Law, said the destination change calls into question whether the pipeline is the same project that was approved.

“Now we’re seeing, effectively, a different project being proposed that is going to an entirely different place,” Smith said. He said pipeline construction started this summer based on what appears to be an attempt to “portray and advance this through existing permits that were made for a project that was going to Prince Rupert.”

“If the provincial government were to approve and advance, or enable the advancement of, the PRGT project in those pretty suspect legal circumstances, in my view, I think that is going to deeply aggravate and increase the likelihood of the types of conflicts on the land that everyone wants to see avoided,” he said.

The decision about whether to proceed with a new environmental assessment will be made by B.C.’s new environment minister following the election.