Elections BC has begun sending voters information about the changes to the provincial electoral map in preparation for the October election, and they are bound to cause some confusion.

The names of 35 ridings have been changed, some of them for somewhat mysterious reasons. Six new ridings have been added in areas of high population growth: Langley, Surrey, Vancouver, Burnaby, the Capital and Kelowna.

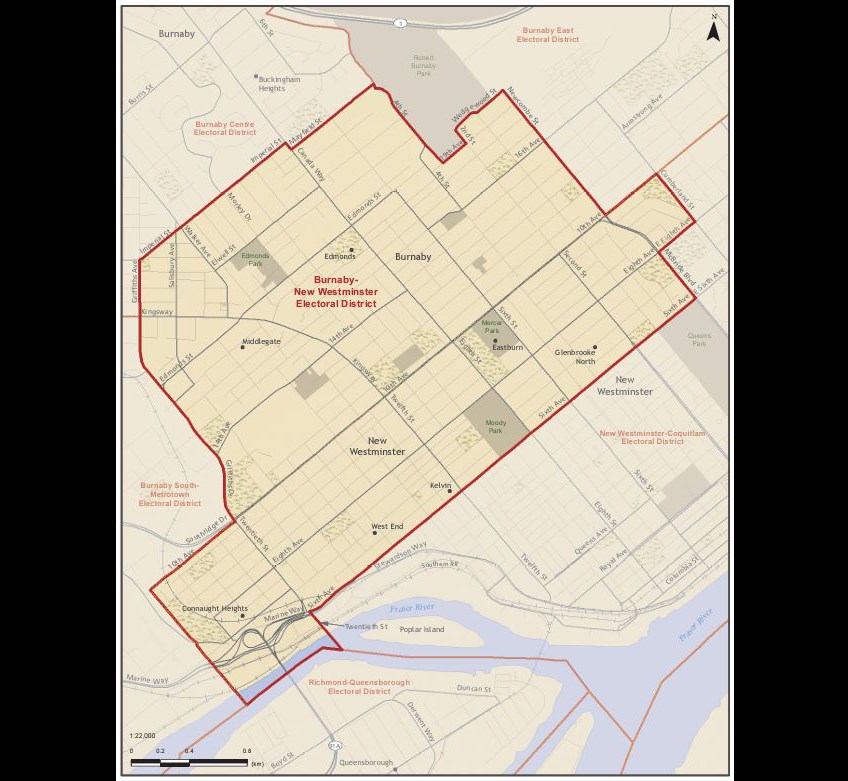

Burnaby will now have five ridings, with the riding formerly known as Burnaby-Edmonds changing to Burnaby-New Westminster. The Burnaby-Edmonds name (I grew up in that riding) was almost 60 years old and first appeared on a ballot in the 1966 election.

The only Burnaby riding retaining its name is Burnaby North. There are four new names (Central, East, New Westminster and South-Metrotown) that will be attached to the Burnaby name.

Two historical riding names are disappearing or are being modified. New Westminster was the name of a single riding for more than 100 years (it appeared during the first provincial election in 1871) but now it is part of two ridings attached to Burnaby and Coquitlam (the Queensborough area had previously been attached to Richmond).

Further afield, the Kootenays town of Nelson will not be on a ballot for the first time since 1903. It had been called Nelson-Creston since the 1933 vote but will now be called by a far blander name: Kootenay Central.

The commission also made some significant changes to the shape and size of some ridings. A preliminary analysis shows the changes benefit the NDP more than other parties.

For example, if you transpose the 2020 election results onto the new boundaries it shows the ridings of Cowichan Valley (won by the Greens) and Fraser-Nicola (won by the B.C. Liberals) would have gone the NDP’s way.

As well, the new boundaries for West Vancouver-Sea to Sky would have meant the Greens, not the B.C. Liberals, would have won that riding had they existed in 2020. Further to that, boundary changes have slightly improved things for the NDP in some key ridings in which they scored historic breakthrough wins in 2020: Boundary-Similkameen, Vernon, Abbotsford-Mission and both Langley seats.

As well, boundary changes mean the Vancouver-Langara riding, currently held by B.C. United MLA Michael Lee, has narrowed the gap between Lee and the NDP.

The six new seats, had they existed in 2004, would have netted a 4-2 split in favour of the NDP. It would have won the new seats in Surrey, Vancouver, Burnaby and the Capital. The B.C. United Party (then called the B.C. Liberals) would have won the new seats in Langley-Abbotsford and Kelowna.

All in all, the changes benefit the NDP the most and further reflect the growing rural-urban divide in this province.

When I began to cover B.C. politics full-time in the 1980s there were eight ridings in Prince George and northward. Today that number hasn’t changed (although Prince George has been added to a southern riding).

But the changes in the number of ridings in Metro �鶹��ýӳ��speak volumes about how our province has changed over the years.

Not quite 40 years ago, there were 33 ridings in Metro Vancouver. That number has swelled to 52 ridings for the October election, a 58 per cent increase.

The biggest growth, of course, has occurred in Surrey. In 1986, it was a two-seat riding. In October, the city will elect 10 MLAs. Electoral map changes tell us a lot.

Keith Baldrey is chief political reporter for Global BC.