New global maps modelling how climate warming will impact sea level rise shows at least 325,000 Canadians currently live on land at risk of annual flooding by 2100.

The data, presented by the U.S. research group Climate Central, marks a 10 per cent increase from previous estimates and does not consider population growth or human obstacles, such as dikes.

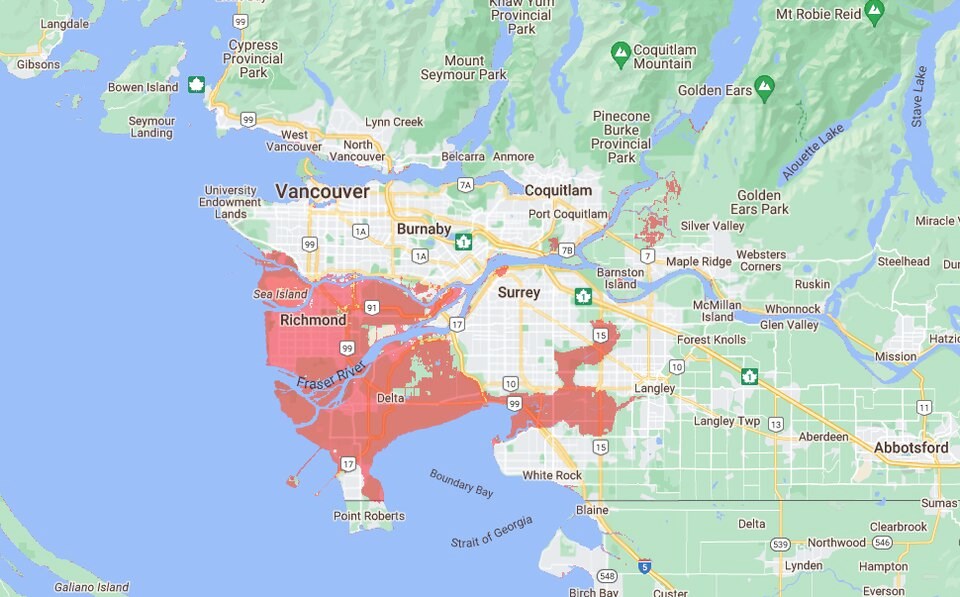

By 2030, show 320,000 Canadians live on land that’s expected to be impacted by a 10-year storm, a number that rises to 351,000 by the end of the century. One of the heaviest hit population centres in Canada is forecast to be portions of Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»that lie south of the Fraser River.

“If you're talking about an area like some of the locations south of Vancouver, where populations are growing, it essentially means people are moving toward these areas where you can expect risk,” said Climate Central spokesperson Peter Girard in an interview.

“In an area like that, these numbers will surely rise.”

By the end of the century, nearly all of Richmond (including the airport), Delta and large swathes of Surrey lie below annual flood levels. That scenario considers a world where countries continue to release carbon pollution at their current rate.

Coastlines across much of the province are forecast to see big changes. Other seriously impacted parts of coastal B.C. include the Southlands neighbourhood of Vancouver, parts of Cowichan Bay on Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island, and a section of coast south of Nanaimo.

New maps use AI to improve accuracy

To build the new maps, Climate Central scientists gathered data from satellite mounted stereoscopic cameras and radar. Next, they fused the two data sets together by running them through a neural network that uses machine learning to pick the most accurate parts of both digital elevation models.

“Previous to this work, most of the global coastal vulnerability assessments used elevation data derived from satellite radar, which does not perform well at all in developed areas — like it kind of sees the top of buildings as hills,” Scott Kulp, the group’s senior computational scientist, said in an interview from Princeton, N.J.

“So it greatly under predicts the vulnerability of these coastal places.”

The latest updates improve the maps' precision by about a third, while incorporating the latest emissions projections from the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to model sea level rise.

The maps also show flood risk from global sea level rise further north and south than was previously possible. In Canada, the map shows a large swath of coast near Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., under increased flooding threat over the coming decades. Flooding due to sea level rise is also now shown across Scandinavia, the north coast of Siberia, and Alaska.

Globally, the number of people at risk due to sea level rise climbs precipitously with time. By 2030, at least 200 million people are expected to live on land under some kind of flood risk — and that number rises by another 93 million by the end of the century, according to the new maps.

More than any other country, China faces the largest threat to human life, with an estimated 29 million people living on land at risk of annual flooding by 2100. In Vietnam, 10 million people lie in a flood path, while in India, nine million people are at risk.

An estimated 1.8 million Egyptians live on land expected to fall into a flood risk zone by century’s end (a near doubling from today), whereas in Brazil, 2.1 million people will face high annual floodwaters by 2100 (a 68 per cent increase from today).

Low-lying island nations like Tuvalu face sweeping changes, with two-thirds of the population is forecast to face some annual coastal flooding by 2100.

Maps not perfect, but intended to point out blind spots

Girard said that in some places, such the Thames Barrier in London or a vast network of coastal defences in the Netherlands, people are already protected from flooding.

“It is true that a number of places that you see are likely protected or somewhat easily protectable in the near term. But when you look into the future, that changes,” said Girard. “So being able to help people identify where the risks are likely to be most acute in the future can help planning for the long term.”

“That's, in some ways, the most important thing we can show in these maps… protected today may not mean protected in the future.”

Kulp added that as soon as data becomes available to map coastal defences across the planet, Climate Central will incorporate it into the flood maps as a “very high priority.”

Until then, added Girard, “the long-term solution is always the same: reducing emissions.”

“If emissions are reduced, the pace of sea level rise slows and communities get a longer window to plan for higher seas and more risk.”