The rise of artificial intelligence has been made possible by large language models — algorithms fed massive amounts of data to the point where they can understand and generate language at a speed and quality at times almost indistinguishable from a human.

But what if those predictive powers were applied to the life experiences of a human being? Could they foresee the future?

In a new , published Monday in Nature Computational Science, researchers from the Technical University of Denmark and Northwestern University in Boston used AI models to “examine the evolution and predictability of human lives.”

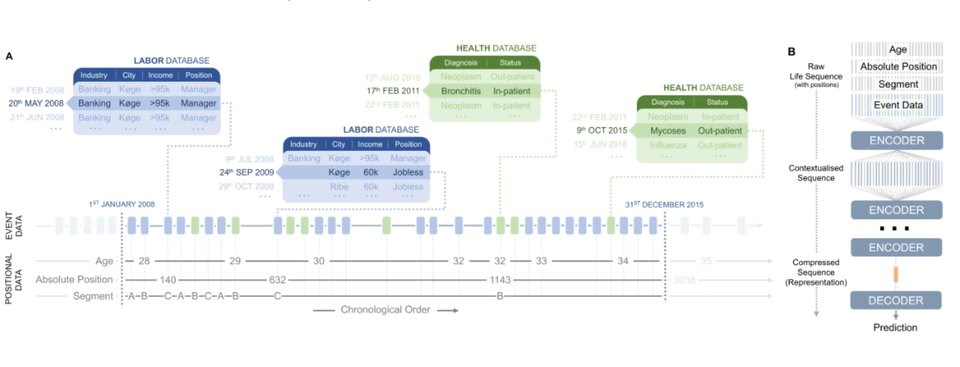

To train the AI model, known as Life2vec, the researchers fed it the registry data of six million Danish citizens from 2008 to 2020, including “day-to-day resolution” of people’s education, residence, income, working hours, and details surrounding their health, such as doctor and hospital visits, diagnosis, patient type and how urgent the visit was.

Sune Lehmann, a professor at the Technical University of Denmark and one the study’s authors, said in a statement that the most exciting part of the study was having access to data that enable an AI model “to provide such precise answers.”

"What's exciting is to consider human life as a long sequence of events, similar to how a sentence in a language consists of a series of words,” he said.

"We used the model to address the fundamental question: to what extent can we predict events in your future based on conditions and events in your past?”

The model predicted a number of diverse life outcomes, from personality nuances to early death, with startling accuracy.

The researchers focused on predicting people's survival from 2016 to 2020, focusing on those who were 30 to 55 years old to make it more challenging.

The results were remarkably similar to what’s expected from studies in the fields of social science, where people with higher incomes or in leadership positions have been found to more likely live longer lives. Males, skilled workers and people who live with mental illness, meanwhile, have been found to face a higher risk of dying young.

The Life2vec model also was able to predict personality traits — such as introversion and extroversion — in line with individual answers provided in The Danish Personality and Social Behaviour Panel study.

Lehmann said researchers are now looking at ways to feed the model images and information about social connections. The more accurate the results, the better researchers might “discover potential mechanisms that impact life outcomes” and find possible “personalized interventions,” the study said.

While many positive applications could come out their findings, the researchers also offered a warning: their work was to see what was possible, and should not be applied in the real world without regulations in place to protect individual rights.