Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»will grow by 50,000 people every year from now until the mid-2040s when four million residents will call the region home, new modelling shows.

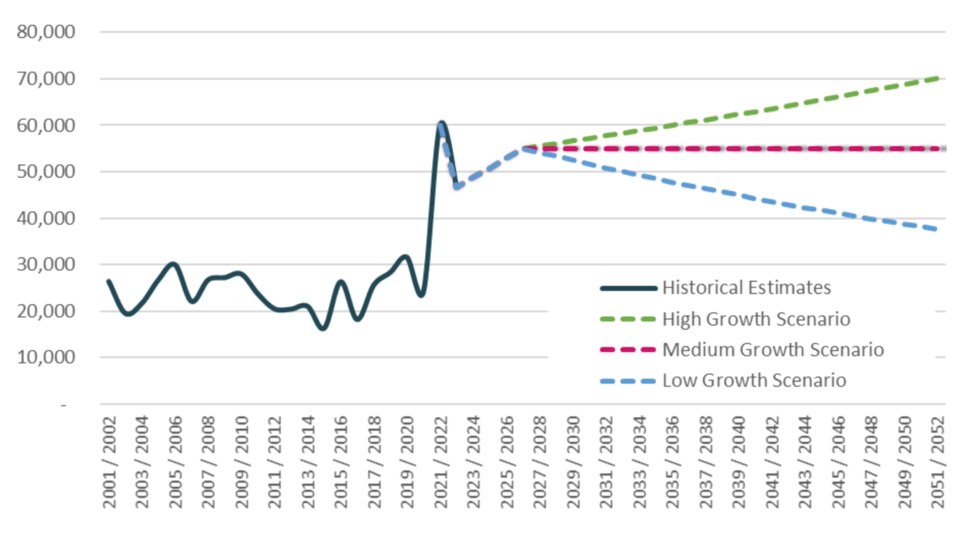

The numbers, contained in a report from Metro Vancouver’s regional planning committee, will be entirely driven by immigration from 2035 onward, when natural increase through new births sinks below replacement levels. Under a , the region was anticipated to climb to 3.8 million people by 2051, a slower growth rate requiring half a million new homes and jobs.

Jonathan Cote, Metro Vancouver’s deputy general manager of regional planning and housing development, said adding another 15,000 residents a year “really adds up” over time.

“What our projections are showing is we are going to be going faster than we have in the past,” he said.

“And no doubt that is going to put pressure on our infrastructure, put pressure on even our social infrastructure to accommodate and adjust.”

Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»receives about 11 per cent of new immigrants Canada receives every year. That’s expected to lead to 55,000 net new immigrants per year under the medium and most likely growth scenario — a projection that sits almost 50 per cent higher than the historical average of 37,500 net new immigrants per year.

The low-growth scenario assumes immigration will slow down to historical averages, whereas under the high-growth scenario, net new immigrants will spike to 70,000 per year by 2051, a doubling of the historic average.

The projections rely on regional land capacity, approved development plans, new census data, increased federal immigration targets, and new policies for non-permanent residents. The resulting population estimates are used to estimate future demand for land, housing, jobs and utilities at a time the regional body is investing billions of dollars in new infrastructure projects to keep up with growth.

“These policy changes, beyond the influence of Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and member jurisdictions, are having a significant impact on regional population projections and are creating a new demographic paradigm for the region,” Sinisa Vukicevic, program manager of Regional Planning Analytics, added in the report.

“The region’s demographic future will not be a simple extension of past trends and growth assumptions.”

About 472,000 immigrants arrived in Canada in 2023. Another 700,000 net non-permanent residents came to the country between July 2022 and July 2023, though the federal government plans to to five per cent over the next three years. This latter group was one of the main drivers of population recovery in the post-COVID-19 period, says Metro staff.

High-, medium- and low-growth scenarios each assume different immigration and fertility rates, with higher immigration typically resulting in a larger share of children and young facilities, says the report. At the high end, immigration is expected to result in a greater proportion of children and younger families.

Migration from other provinces to Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»will continue to be a “minor contributor” to its overall population growth. Within the province, the flow of migrants is decidedly moving away from B.C.’s largest urban area.

In the decade between 2012 and 2022, migration from across B.C. accounted for only 0.3 per cent of the region’s growth, much lower than the one per cent — or 25,000 people — who left the the region for another part of the province every year.

A Metro analysis showed seniors tend to move to other parts of the province. Working-age residents, meanwhile, tended to move to the surrounding municipalities, like Mission, Abbotsford and Chilliwack.

Cote said the new numbers are not expected to derail Metro Vancouver's infrastructure spending plans over the next few decades. But as the century wears on, shifts in who is governing at the federal level could upend immigration policy and complicate how the regional body ensures there's enough water and sewage capacity for all its residents.

“Will this faster growth be the new norm? We’re anticipating that it will be,” Cote said.