LONDON (AP) — Britain's drug regulator approved the Alzheimer's drug Kisunla on Wednesday, but the government won't be paying for it after an independent watchdog agency said the treatment isn't worth the cost to taxpayers.

It is the second Alzheimer's drug to receive such a mixed reception within months. In August, the U.K. regulator authorized while the same watchdog agency issued draft guidance recommending against its purchase for the National Health Service.

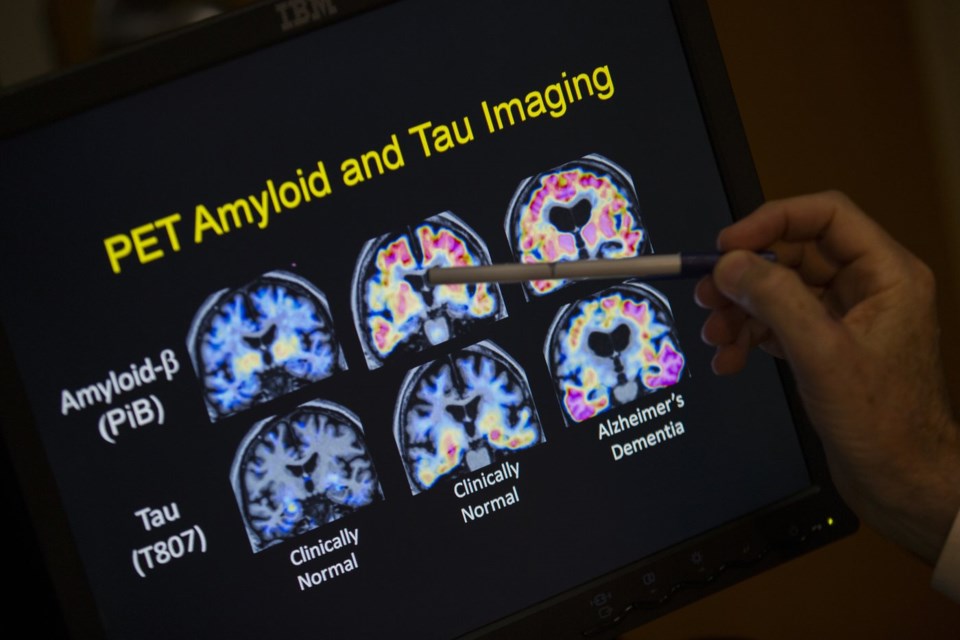

In a statement on Wednesday, said Kisunla “showed some evidence of efficacy in slowing (Alzheimer's) progression” and approved its use to treat people in the early stages of the brain-robbing disease. Kisunla, also known as donanemab, works by removing a sticky protein from the brain believed to cause Alzheimer’s disease.

Meanwhile, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, or , said more evidence was needed to prove Kisunla's worth — the drug's maker, Eli Lilly, says a year's worth of treatment is $32,000. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration Kisunla in July. The roll-out of its competitor drug Leqembi has been slowed in the U.S. by spotty insurance coverage, logistical hurdles and financial worries.

NICE said that the cost of administering Kisunla, which requires regular intravenous infusions and rigorous monitoring for potentially severe side effects including brain swelling or bleeding, “means it cannot currently be considered good value for the taxpayer.”

Experts at NICE said they “recognized the importance of new treatment options” for Alzheimer's and asked Eli Lilly and the National Health Service “to provide additional information to address areas of uncertainty in the evidence.”

Under Britain's health care system, most people receive free health care paid for by the government, but they could get Kisunla if they were to pay for it privately.

“People living with dementia and their loved ones will undoubtedly be disappointed by the decision not to fund this new treatment,” said Tara Spires-Jones, director of the Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. “The good news that new treatments can slow disease even a small amount is helpful," she said in a statement, adding that new research would ultimately bring safer and more effective treatments.

Fiona Carragher, chief policy and research officer at the Alzheimer's Society, said the decision by NICE was “disheartening,” but noted there were about 20 Alzheimer's drugs being tested in advanced studies, predicting that more drugs would be submitted for approval within years.

“In other diseases like cancer, treatments have become more effective, safer and cheaper over time,” she said. “ We hope to see similar progress in dementia."

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Maria Cheng, The Associated Press