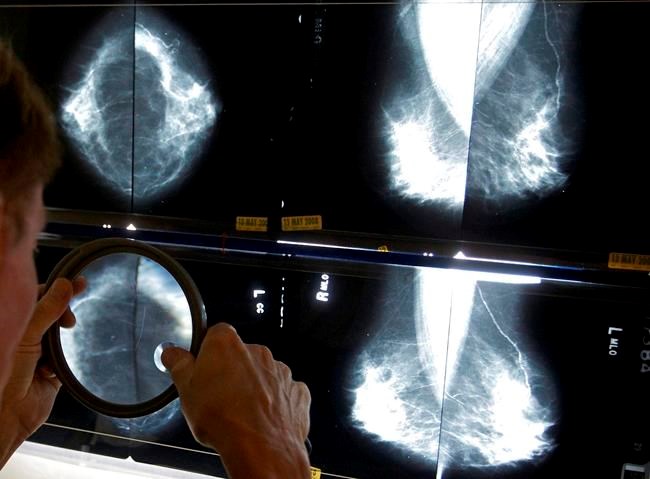

ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — A breast cancer survivor in Newfoundland and Labrador is questioning how nearly 14,000 more mammogram results in the province have been placed under review because they were analyzed on improper screens.

The news Wednesday brought the number of mammograms now under review to more than 16,500.

"How the hell did this happen?" asked Gerry Rogers, the former leader of the province's NDP. Rogers won a Gemini Award for her 2000 film, "My Left Breast," about her breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.

"What was the protocol?" she said in an interview Wednesday. "What were the safeguards in place to ensure that our diagnostic equipment was up to national standards?"

Rogers was a prominent patient advocate during the Cameron Inquiry, a judicial investigation launched in the province in 2007 to determine why hundreds of patients received the wrong breast cancer test results between 1997 and 2005.

"It took so long, particularly for women who had breast cancer, to … re-establish a confidence in the system," Rogers said of the inquiry. "Now this just kind of blows it all apart again."

Three of the province's four health authorities said Wednesday they were collectively reviewing results from approximately 13,884 mammograms. The images represent about 11,751 patients, officials told reporters.

The news came after the province's Central Health authority said last week that it was reviewing mammograms from about 3,000 patients. The images had been analyzed on screens with three-megapixel resolution instead of the recommended resolution of five megapixels.

A preliminary review of images from 837 Central Health patients revealed "four potential discrepancies or differing interpretations" of the mammograms, officials said earlier this week. The mammograms under review in Central Health cover a period between Nov. 1, 2019, and Aug. 19, 2022, officials said.

In the Eastern and Labrador-Grenfell Health authorities, the images being scrutinized cover a period beginning Sept. 18, 2018, and ending last week.Â

Those from Western Health, meanwhile, date as far back as October of 2013. The three other health authorities have said they didn't have the data-collection processes in place to determine whether the three-megapixel screens were used beyond 2018 or 2019.

Rogers said she was particularly concerned that mammograms were read on out-of-date screens for nearly nine years at Western Health.

Dr. Angela Pickles, who is clinical chief of medical imaging with the province's Eastern Health authority, told reporters Wednesday that most women who get a mammogram do so regularly.

"Most women, depending on family history and a few other factors, have an examination performed yearly or every two years," Pickles said. "So, during this time frame we have landed on, most women will have had a followup examination performed."

Pickles said last week that the screens with three-megapixel resolution and five-megapixel resolution are "so close that the human eye struggles to differentiate any small occurrences at this level."

She said an accepted margin or error or "difference in (medical) opinion" in radiology is typically between one and five per cent.

Kenneth Baird, interim president and chief executive officer of Eastern Health, said Wednesday that a "quality review" will be launched to determine how and why the mammograms were viewed on improper screens, and what might be done to ensure it doesn't happen again.

As for reviewing the images themselves, the health authorities may have to contract help from outside the province in order to get the work done without slowing down normal workflow, Baird said.

Officials noted that the risk to patients as a result of the errors appears to be low.Â

Rogers, however, was not comforted. She said the possibility of any error can be "incredibly frightening" for patients undergoing breast cancer screening.

"If they're concerned, they have a right to be concerned right now," she said. "I think it's a totally sane reaction to this very difficult situation."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 31, 2022.

Sarah Smellie, The Canadian Press