In âOccupied City,â a young woman with an even voice narrates, with rigorous specificity, Nazi encounters and crimes throughout Amsterdam during World War II. The accounts go address by address, and so does McQueenâs camera.

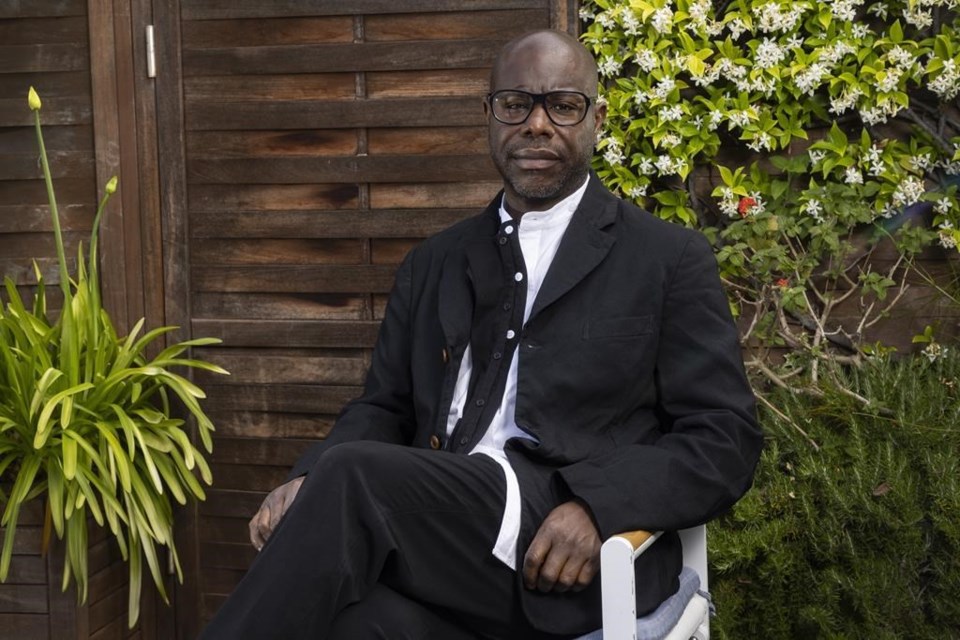

Yet the images that play throughout are of modern day Amsterdam. In the roving, 4 hour-plus documentary made by McQueen, the â12 Years a Slaveâ director, with his partner, the Dutch documentarian and author Bianca Stigter, past and present are fused â or at least provocatively juxtaposed.

The effect can be startling, stirring and confounding. An elderly woman shifts to country music in an apartment complex where, weâre told, a family was once arrested and sent to a concentration camp. A radio throbs with Bob Marley in a park where German officer once resided in the surrounding townhouses. A boy plays a virtual reality videogame where an execution took place.

âItâs almost like once upon a time there was this place called Earth,â McQueen said in an interview alongside Stigter.

âOccupied City,â which A24 releases in theaters Dec. 25, includes no archival footage or talking heads. Instead, it invites the viewer to consider the sometimes hard-to-fathom distance between one of historyâs darkest chapters and now. Itâs about remembering and forgetting.

âYou want to wake people up and at the same time take them with you,â says McQueen, a British expat who has made Amsterdam his adoptive home with Stigter and their children.

The film is rooted in Stigterâs illustrated book which likewise catalogued the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam and the methodical murdering of its Jewish citizens. Stigter and McQueen have researched their own address. A few doors down, McQueen says, a Jewish man in hiding paid for his keep by teaching a familyâs child how to play piano. Their lessons were conducted quietly by tapping on the table.

âOccupied Cityâ details how the Nazi occupation unfolded, door to door, name by name. At the same time, it can be hard to reconcile those accounts with the accompanying footage that captures mostly civic harmony throughout modern Amsterdam. Though âOccupied City" touches on monuments and museums to the Holocaust, its imagery mostly lingers on the thriving life of a city. Life moves along, relentlessly.

âThe present erases history,â says McQueen. âThereâs going to be a time when no one is going to be around who knew certain people. It kind of echoes whatâs happening with the Second World War. Thereâs not a lot of people around who can testify about what actually went on in that time. Theyâre all passed. This film in some ways is erecting those memories in another way.â

McQueen is currently in post-production on a more traditional film about WWII set in London: âBlitz,â for Apple, starring Saoirse Ronan. Though in many ways McQueen is among the most fiercely contemporary filmmakers working, history has deeply animated much of his work. â12 Years a Slaveâ plunged into slavery-era America. His spanned generations of West Indian immigrant life in London. He has dramatized the Irish hunger strike of 1981 (âHungerâ) and, most recently, the (âGrenfellâ), in which 72 died.

âI feel recording is very important. Witnessing is very important. Not looking away is very important,â he says. âThe thing about cinema thatâs powerful is an audience and a community witnessing something together. Thereâs nothing more special, thereâs nothing more powerful than to have this kind of communal witness to something.â

Stigter considers âOccupied Cityâ not a history lesson but âan experience.â

âYour brain is programmed to match, to put together what you hear and what you see,â she says. âHere, sometimes itâs hard to find that link. And sometimes you find it.â

The length of âOccupied City,â which is playing with an intermission, encourages rumination. Drifting from narration to imagery and back again, McQueen says, is part of the experience. He would rather it was longer, if anything.

âThere is a 36-hour version of this. We shot everything in the book. Maybe one day Iâll get a chance to show that,â says McQueen. âThe actual method of shooting was about that. You just have to let it happen.â

âThe ordinary becomes extraordinary,â he adds. âAs you get older, you realize itâs the small things in life that are the treasures. Thereâs a value. Thereâs a value to sitting with a cup of tea with a biscuit. Iâll have it any day.â

In the context of such horrors, some scenes, like a boy and girl gently kissing, become âmonumental,â Stigter says. Ghosts are everywhere, whether theyâre acknowledged or not. In the film, Amsterdam is also literally occupied â busy, running errands, biking and, more often than not, on their phones. âOh my God,â sighs McQueen, shaking his head. âThere it is in black and white, even though itâs in color.â

Stigter and McQueen made âOccupied Cityâ through the pandemic so it also shows the waves of COVID-19, from lockdown to vaccine protests to parties, once again, in the street. Another upheaval is quickly moved on from. Other losses come and go. The film is dedicated to Stigterâs father, who died a year and a half ago.

âYou try to hold onto things but they always slip away. Itâs like this film. After four hours and 22 minutes, itâs done,â says McQueen. âWhat I want this film to be is almost like tossing a stone into a pond. The ripple effects afterwards, how it enters the viewerâs everyday life, thatâs what I hope for.â

___

Follow AP Film Writer Jake Coyle on Twitter at: â

Jake Coyle, The Associated Press